Art does help you process; it does help you see your own situation from a different point of view; it does help you either process that situation or actually distract from that situation, which is equally valid. Fantasy is again another of those human necessities, and to be able to disappear in an alternative reality is, I think, now certainly needed.

(Tamara Rojo “The Art of Empathy” 13:25-14:22)

Ballet at War Now

Early 2020 was truly auspicious for British ballet. It began with Northern Ballet’s 50th Anniversary Celebration Gala, featuring dancers from a range of British ballet companies: Birmingham Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, the Royal Ballet and Scottish Ballet. There were glorious performances of Le Corsaire by English National Ballet, followed by three performances of their 70th Anniversary Gala, highlighting the range of works in their repertoire over the years and the strength of the Company in terms of both technique and character. Cathy Marston’s The Cellist, her first work for the main stage at the Royal Opera House, premiered in February. And then there was the promise of other major new works: Kenneth Tindall’s Geisha for Northern Ballet, and most excitingly Akram Khan’s much anticipated Creature for English National Ballet – their third collaboration.

With the announcement of COVID-19 as a global pandemic this promise was largely unfulfilled: although Geisha received its world premiere in Leeds to substantial acclaim (Brown, M.; Roy; Hutera), the tour was cancelled, along with all performances in April and May of Red Riding Hood; and to our utter dismay, Creature was postponed weeks before the premiere. Since we wrote our spotlight post on British ballet in lockdown, further cancellations and postponements have ensued, including both English National Ballet’s and the Royal Ballet’s Swan Lake and Scottish Ballet’s The Scandal at Mayerling, all of which are vital to the finances of the respective companies.

It goes without saying that the primary purpose of any ballet company is to produce and perform live performances, and that these performances require daily training and rehearsals for the dancers and musicians, as well as work behind the scenes from a whole host of people of different skill sets, including set and lighting designers, wardrobe and technical staff, and physiotherapists, to say nothing of teachers, coaches and directors. For all of these people, whose communities are sometimes referred to as a “family” (Weiss; Wulff 89), the current loss of this purpose must seem like a bereavement. Further, for dancers and musicians in particular, who perform in groups as well as individuals and rely on the extreme skill of their bodies to fulfil their profession, being cut off from their working environment with the space and facilities they require must feel far more disorienting, and constitute a far greater breach to their professional identity, than for those of us who are locked out of our offices.

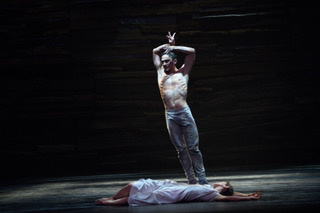

Understandably perhaps, the language of war pervades the discourse of the pandemic. Journalists have highlighted vocabulary used to describe our relationship with the virus: Dominic Raab looked “shell-shocked” before chairing the “war cabinet” (Hyde); the virus is a “cruel enemy” that must be defeated in battle (Freedman). The death toll is constantly updated in the news, and people are anxious about their loved ones, and lose them without being able to bid them a real farewell. In addition, there is a sense of dislocation as we relocate our work to our homes; this sense of dislocation must be especially acute for dancers who have to practise, sometimes alone, in limited and limiting spaces at home. And then there is time. Literary scholar Beryl Pong describes wartime life as having “peculiar temporalities”: it is “a period when one feels that time has stopped, but also when it simply cannot pass by quickly enough” (93). So we experience dislocation in both time and space, the two elements that choreographer Merce Cunningham regarded to be the only essentials to dance other than the moving body (qtd. in Preston-Dunlop). This dislocation, the attendant physical restrictions and mental pain are in our opinion most movingly expressed in the film Where We Are. Organised by Alexander Campbell of the Royal Ballet with choreography by Hannah Rudd of Rambert, the film features Campbell’s colleague Francesca Hayward, freelancer Hannah Sveaas, and Jeffrey Cirio of English National Ballet. The movements are predominantly performed in the near space of the dancers’ kinesphere, arms folding over their bodies, hands across their mouths and necks, sometimes with tense fluttering gestures; all indicating both the restrictions and the anxiety experienced by the performers in their current situation.

But despite the poignant message expressed by Where We Are, the film also symbolises hope. It is not only that Cirio utters the words “I’m so hopeful”, but the film is one of the many activities undertaken by the dancers of this country that are witness to their resourcefulness and creativity. In our last post we outlined some of these activities, from the practical, such as classes targeted at a wide range of demographic groups, to the highly entertaining films made by Sean Bates and Mlindi Kulashe of Northern Ballet. Since we wrote that post, there have been many many other delightful offerings. One favourite is English National Ballet’s Isabelle Brouwers’ Instagram video post in which she cooks a highly nutritious meal, while simultaneously explaining to us how to access the nutrients for optimising dancers’ performance and magic them up into a delicious meal. This video was made after Brouwers gained a diploma in Sports Nutrition with distinction (Bellabrouwers). Another favourite is completely different in nature, though equally upbeat: a compilation by no fewer than ten Royal Ballet dancers performing the “Fred Step”, Frederick Ashton’s signature movement phrase, in a variety of guises and locations (Frederick Ashton Foundation).

Dancers’ projects are highly visible – they are ideal fare for social media, and their ventures also make for engaging feature articles in newspapers, magazines and news websites, garnering such catchy headlines as “How should everyone keep fit during lockdown? Just put on some music and move!” (Monahan), “These Ballet Dancers are Keeping Limber under Lockdown” (Rosado), “Dancing in the streets: Royal Ballet stars rock to new Rolling Stones song” (Wiegand). For us, however, it was noticeable that later in May and well into June the focus of articles shifted towards the vexed question of reopening theatres and the arduous process of preparing dancers for a return to the stage (Craine; Crompton “What will it take?”; Mendes; Sanderson). This development seemed to be a response to two events: the first steps to the easing of lockdown with the opening of “non-essential shops”, and the establishment of a government Cultural Renewal Task Force, which notably included the presence of Tamara Rojo, Artistic Director of English National Ballet. The resultant growing concern about the future of the arts resulted in a series of petitions and an escalating flurry of anxious activity on social media leading up to a cautious sense of relief triggered by the announcement of a £1.57 billion rescue package for the arts, culture and heritage industries from the Treasury.

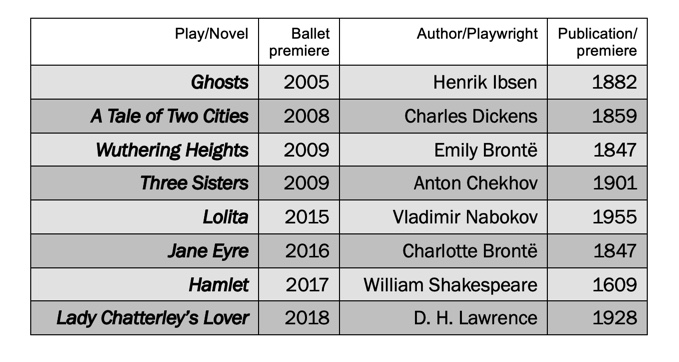

This situation calls for a different kind of creativity from company and theatre directors, one that is less visible, less immediately engaging and eye-catching than videos of performances (including cooking!). Yet this kind of problem-solving creativity and resourcefulness is vital for the future of ballet in this country, and is crucially a long-term endeavour. Someone who has brought greater visibility to this kind of creativity is Tamara Rojo, who is an avid theatre goer, as well as being passionate about the development of ballet as an art form and the part that her own company is playing in this. In June, she participated in three events in which the repercussions of lockdown for the performing arts were included in discussion (“The Art of Empathy”; “The Future of Live Performance”, “Tom and Ty Talk”). All of the conversations could be described as “equally sobering and optimistic” and “bittersweet” (@uk_aspen). These oxymoronic phrases capture the predicament faced by artistic directors, who must be realistic in balancing the books as well as idealistic in holding on to their vision for their art form. At this time, in the face of the plummeting UK economy and the uncertainty regarding the nature of the virus, artistic directors are confronted with a predicament of far greater proportions than is usually the case: depleted income, dancers who require months to return to full physical and mental preparedness for performance, and the likelihood of low box-office takings when theatres reopen, due to new social distancing regulations. Exacerbating matters is the status of the arts in the UK, implied in Sarah Crompton’s statement: “with so many demands on the Exchequer, the needs of culture may seem low on the list” (“What will it take?”).

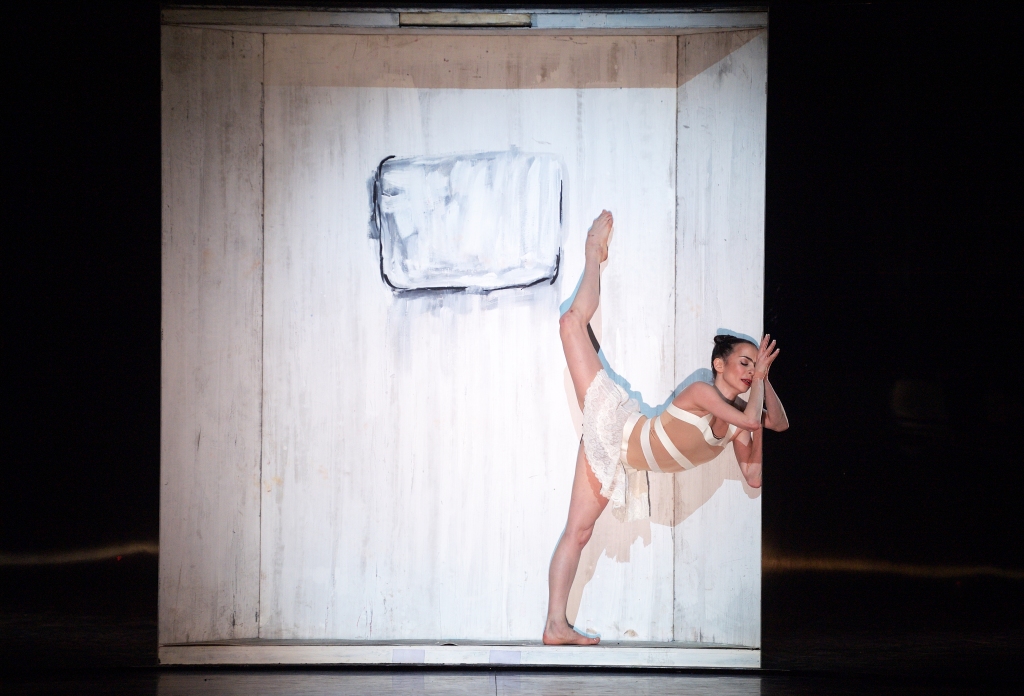

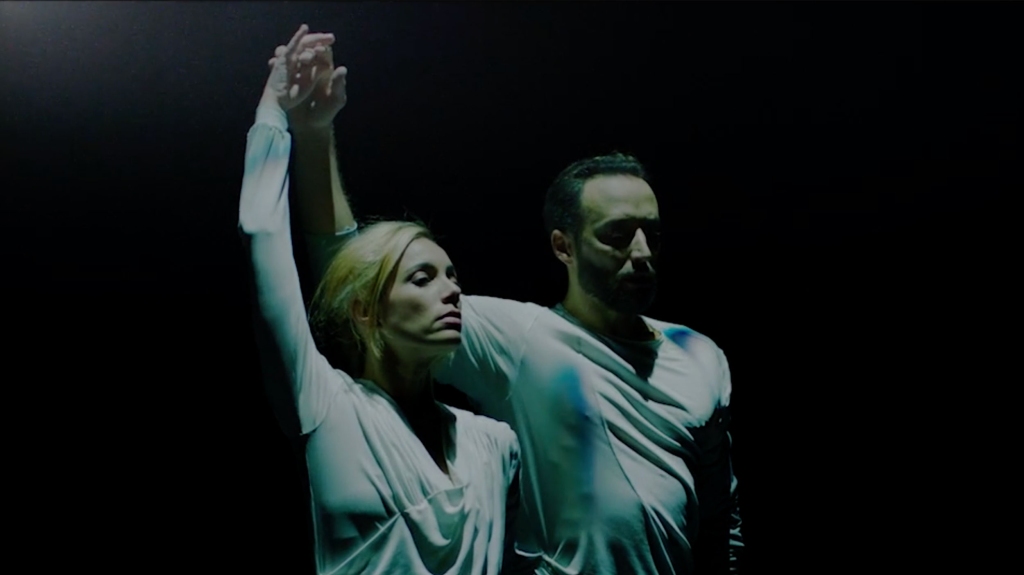

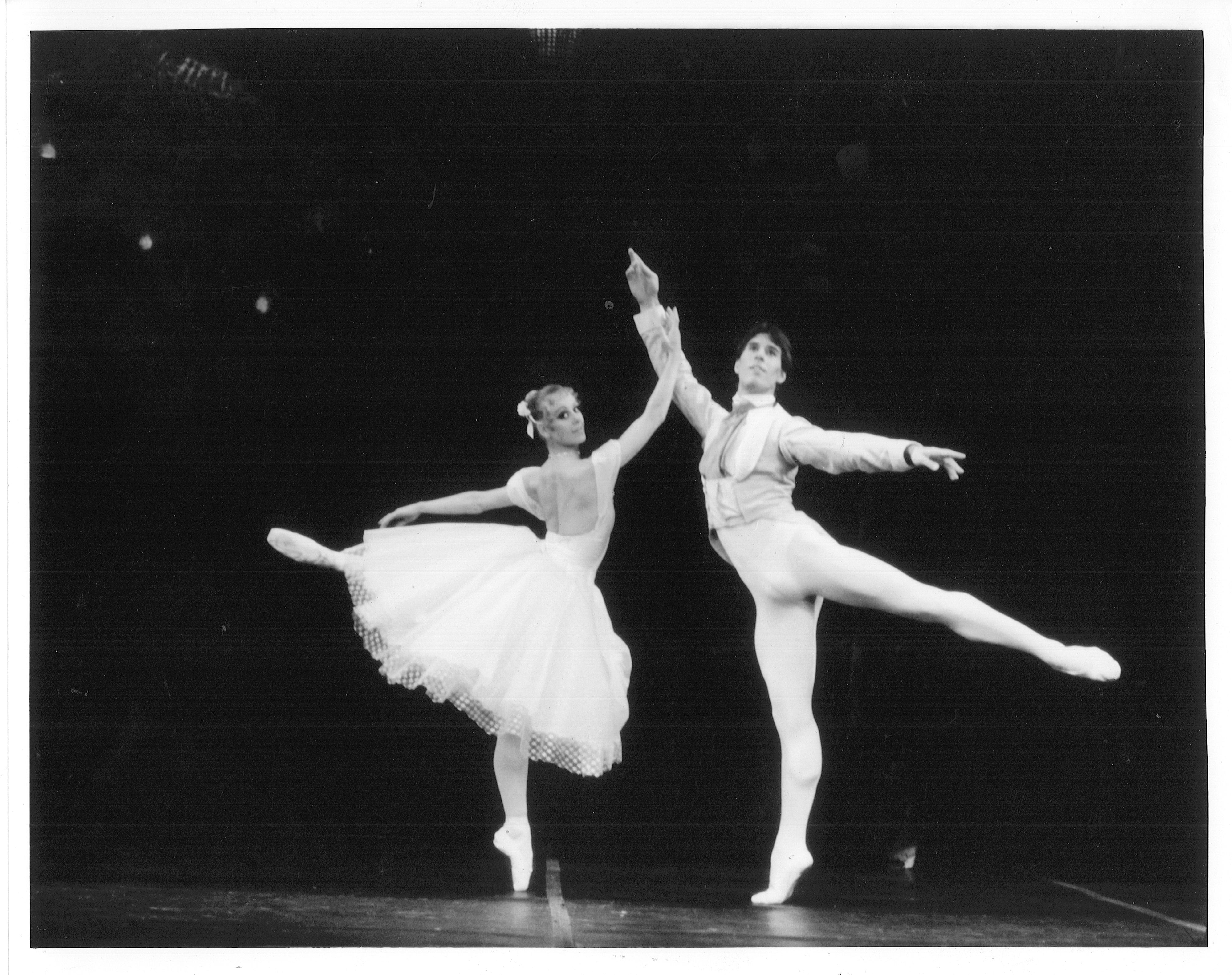

Happily, ballet audiences have all benefited from creative solutions already. Initially companies shared previously recorded performances online. More recently, the Royal Opera House “re-opened” with Live from Covent Garden, a concert series of ballet and opera streamed live from the Opera House, but minus the audience. Members of the Royal Ballet danced Morgen, a new creation by Wayne McGregor, Frederick Ashton’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits (1978), and pas deux from Concerto (MacMillan, 1966) and Within the Golden Hour (Wheeldon, 2008). Of necessity, these were small-scale performances danced by couples living together or individuals dancing alone. Similarly, wife and husband Erina Takahashi and James Streeter of English National Ballet performed the “White Swan pas de deux” at Grange Park Opera House.

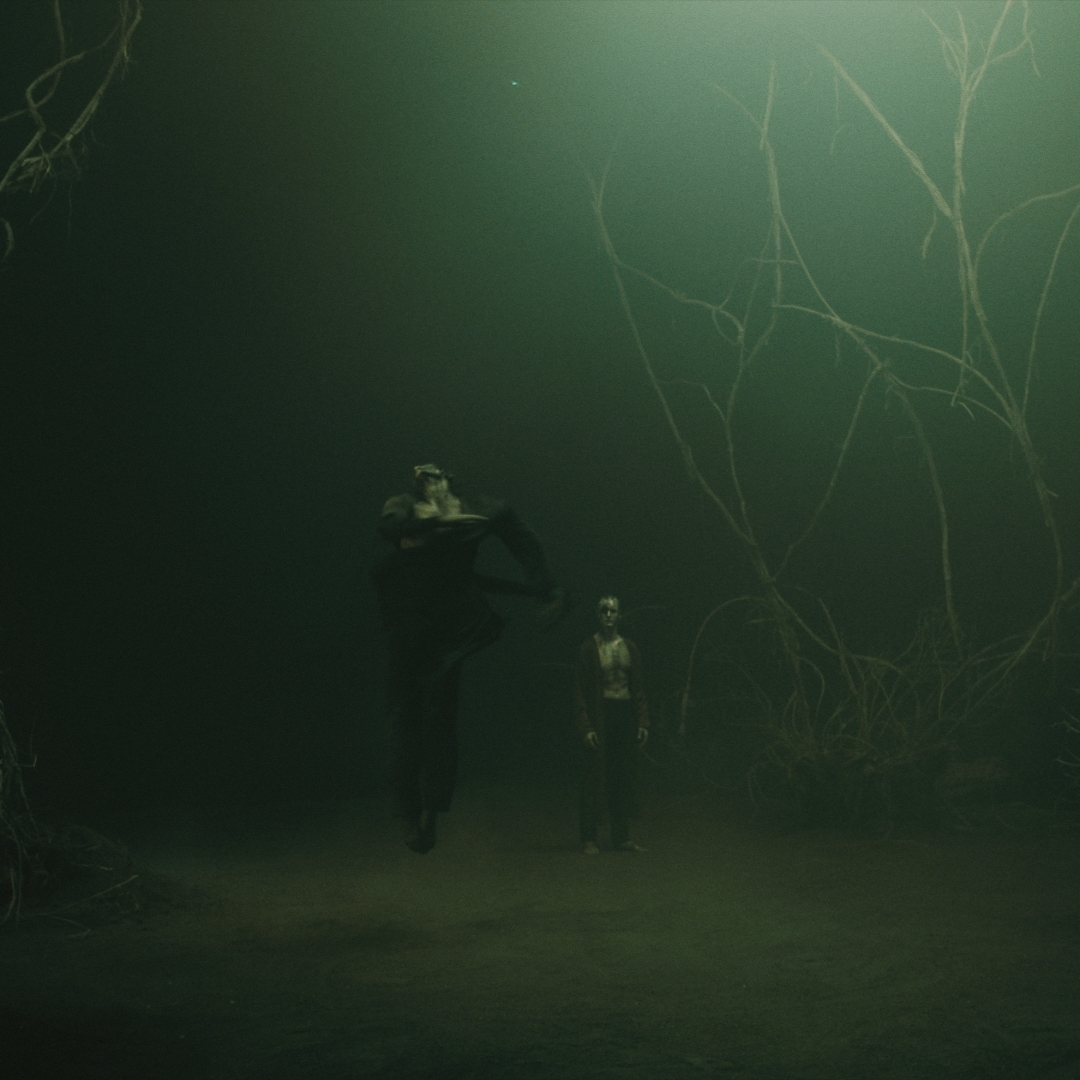

Ballet companies do, of course, offer a lot of digital content on their websites in order to both inform and entice their audiences. These include short dance films made specifically for the camera in a variety of settings, such as Ballet Black’s Mute, performed in the Thames Estuary as part of Mark Donne’s Listening with Frontiersman (2016), Scottish Ballet’s Frontiers (2019), filmed in outdoor locations around Glasgow, and the ambitious Ego from Northern Ballet, which moves from the home of the characters to the London tube, to Lytham St. Anne’s seafront. But since the middle of March, of course, the only way for companies to share content has been online.

We have no doubt all experienced how life under lockdown has expanded our use of technology, and the potential advantages of this, for example, in terms of the possibility for some of us to work from home for a portion of the week, and the positive impact a continuation of this practice may have on productivity, the environment and personal finance (Bayley; Courtney). Similarly, Rojo believes that digital performances and events will, in the future, run in parallel with traditional live shows as part of the core business, rather than digital content on company websites and social media platforms being used predominantly as marketing tools (“The Art of Empathy”). In our opinion, this is the kind of creative thinking that could bring a boost to ballet as an art form by attracting new audiences, making it more accessible and inclusive, while generating new channels of revenue for companies.

Let’s finish this section with a war analogy from LBC’s radio presenter Nick Abbot. He likens life in lockdown to being in a bunker: while we’re in the bunker we’re safe, but we are uncertain of what will meet us when we emerge, and what the repercussions will be of occurrences that have taken place while we have been sheltered in our bunker. But we do know that as well as performing in theatres, albeit theatres bereft of audiences, dancers are starting to take class again in their company studios that have been made safe for them; and we have a date for the opening of indoor theatres with socially distanced audiences. So step by step dancers are emerging from their bunkers, and Rojo is confident that we, their audiences, will follow suit once theatres have also been made safe (“The Art of Empathy”). As far as we are concerned that will definitely be the case, as our thoughts are perfectly encapsulated by Crompton’s eloquent description of the current “absence” of live theatre performances as “an aching hole where something rich and vibrant used to live” (“What will it take?”).

Ballet at War Then

To lovers of ballet, the story of how the infant British ballet flourished against all the odds during the course of World War II is now a familiar and triumphant episode in the history of the art form in this country (Brown, I.; “Dancing in the Blitz; Mackrell”). In fact, we have written twice about this phenomenon in previous posts :“The Sleeping Beauty Now & Then”; “British Ballerinas Now & Then”.

Given the current international standing of British ballet, it is easy to forget that ballet as an established art form with a national company and school and distinctive style of choreography and performance with internationally celebrated dancers does not have a long history in this country, in contrast to the case of France, Russia or Denmark. As you are doubtless aware, the contemporary dance company Rambert started life as a ballet company named after its founder Marie Rambert, and in fact this was the first ballet company to be established here. However, by the outbreak of war, Ballet Rambert was still only in its second decade, and Ninette de Valois’ Company, later to become the Royal Ballet, had been founded only eight years previously.

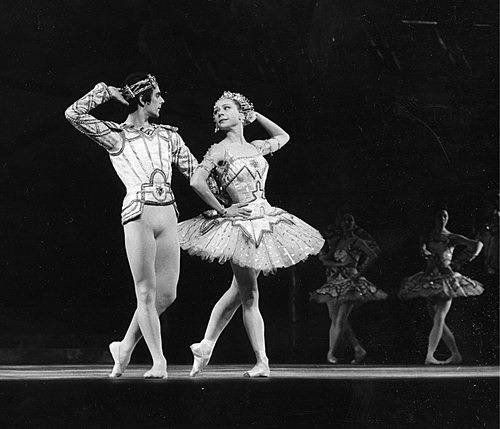

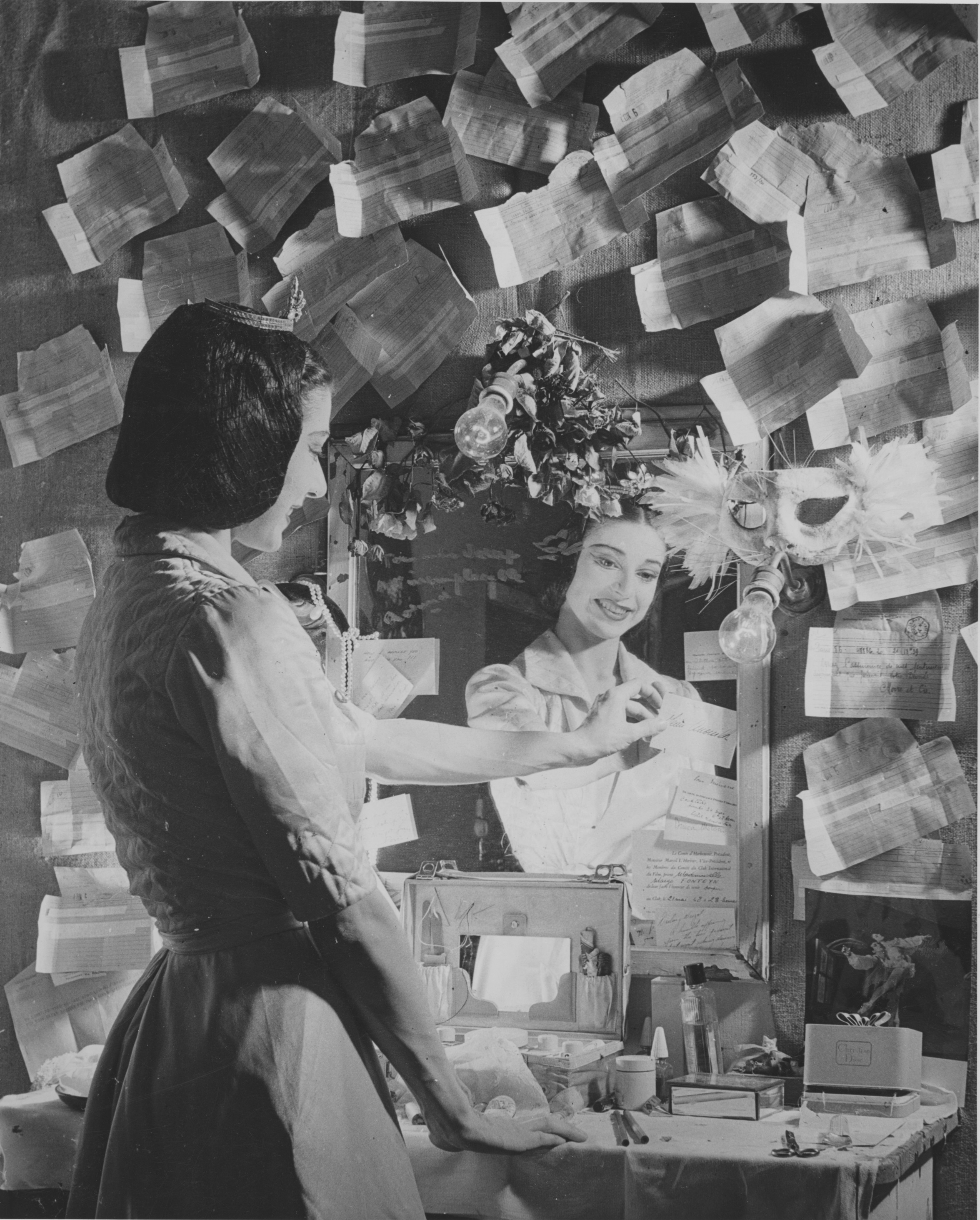

As in the current crisis, the War instigated debates regarding the function and value of the arts, and whether male dancers would serve their country more effectively by joining the armed forces, or in their highly skilled profession, which would allow them to bring the kind of benefits to their audiences that we experience through art, ranging from joy, solace and escapism, to emotional resonance and intellectual stimulation (Eliot 91). Considering the early stage of British ballet’s development at the time, the advent of war could have been catastrophic for the art form. Companies still needed to shape an identity through repertoire and the development of a distinctive style; and they needed to build a loyal following. Even during the Phoney War, conscription, along with the day-to-day problems of rationing, blackouts and restrictions on public transport, all impacted on those involved in ballet, with potentially long-term devastating effects.

At the start of the War, theatres were closed, causing problems with performing opportunities. However, in the pithy words of Alexander Bland, “It soon became apparent to the authorities that a total cessation of normal recreation was more damaging to Londoners than a few bombs” (65). Evidently, access to the arts, including ballet, was perceived as a necessity to the psychological wellbeing of the capital’s residents, and consequently a useful means of boosting the morale of the population, whether or not they were already familiar with ballet as a performance art. Despite this, availability of suitable performance spaces continued to be a problem in London due to the repurposing of important venues: the Royal Opera House became a Mecca Dance Hall, and Sadler’s Wells (home of the Vic-Wells/Sadler’s Wells Ballet) was used as a centre for air raid-victims (Eliot 34).

Two institutions were set up to promote and support the arts: CEMA (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts) and ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association). Although these organisations were privately run, both were supported by the government, indicating the value attributed to the arts at this time (Eliot 33). In addition to addressing concerns about the mental health of both civilians and members of the armed forces, these organisations proved invaluable in ensuring work for artists in their different fields (34-35). Over the years of the War ballet companies toured the provinces as well as larger cities, staging shows in an array of different venues in addition to theatres, including local halls, military bases, munitions sites, factories, and aircraft hangars, thereby bringing ballet to new audiences. In fact, Ballet Rambert were performing for the Codebreakers of Bletchley Park as Germany surrendered in 1945 (Simpson). There was also lunchtime ballet and teatime ballet, resulting in an increase in the usual number of performances (Eliot 52-3). This combination of diversity of location and frequency of performance made ballet central to people’s everyday lives (58).

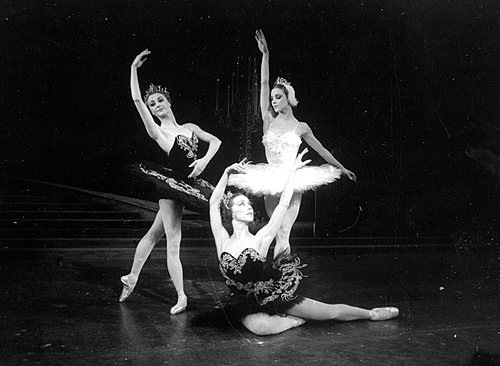

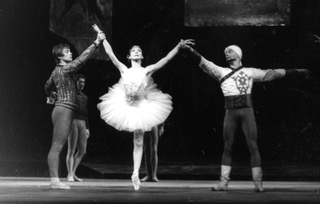

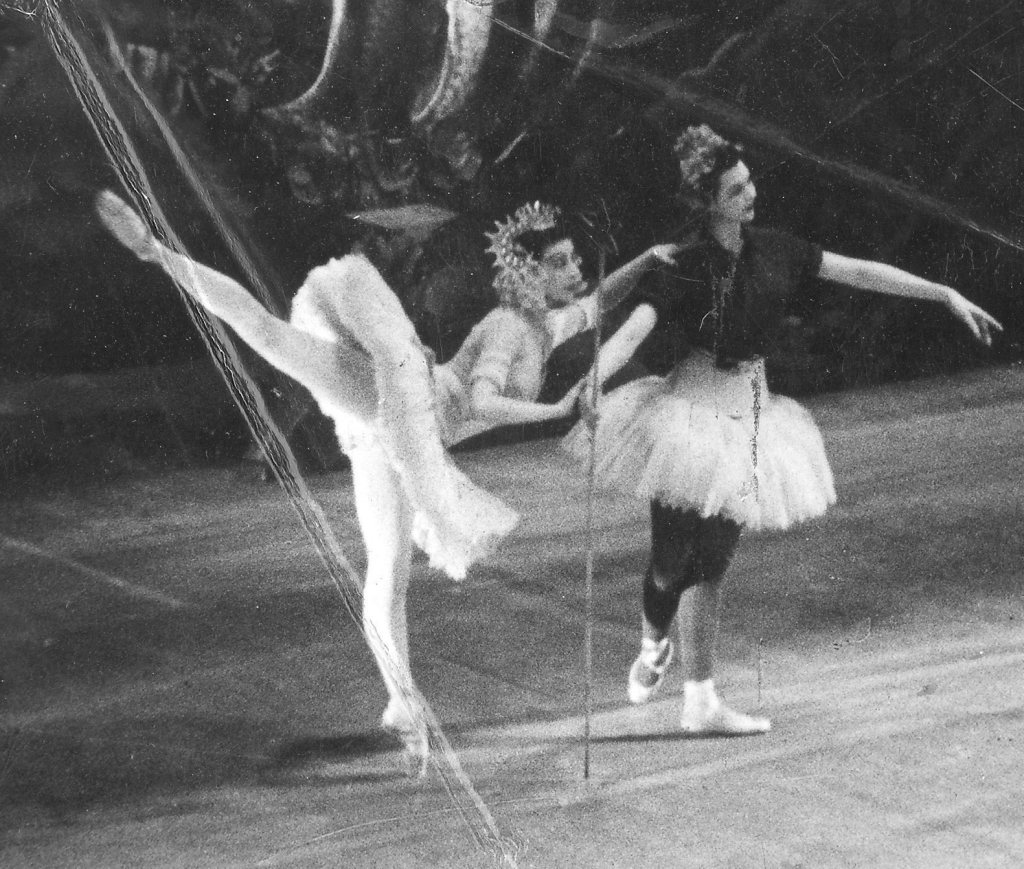

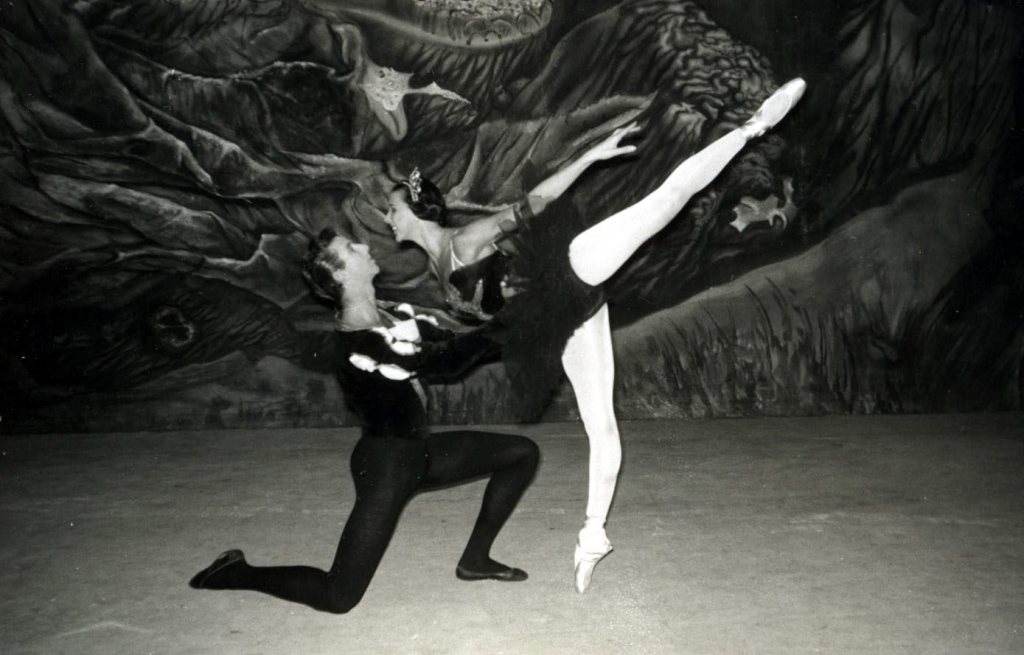

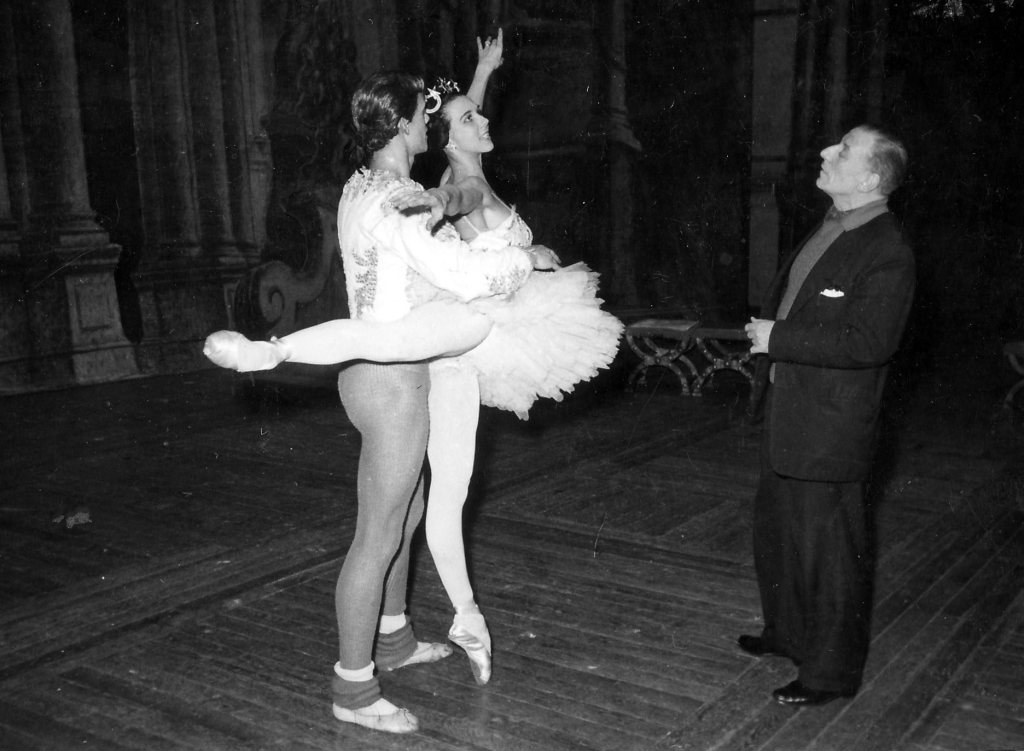

The necessity and stringencies of touring, catering for new audiences, and producing performances with severely depleted numbers of male dances required imagination and resourcefulness from the various staff members of ballet companies. Adapting the repertoire to such an assortment of unusual spaces must have called for constant thinking outside the box. An orchestra was a luxury, so Constant Lambert, Music Director of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, and Hilda Gaunt, Rehearsal Pianist, accompanied the dancers on two pianos. Absent male dancers were replaced by young inexperienced colleagues (Eliot 52), although sometimes they were able to participate in performances at short notice when they were on leave (90). Repertoire was selected to accommodate the situation, with Les Sylphides (Fokine, 1909) a regular item in the performances of many companies: it was already an audience favourite; it required only one male dancer; and Chopin’s music was originally composed for piano.

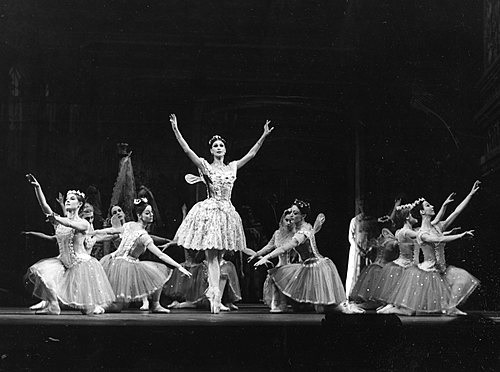

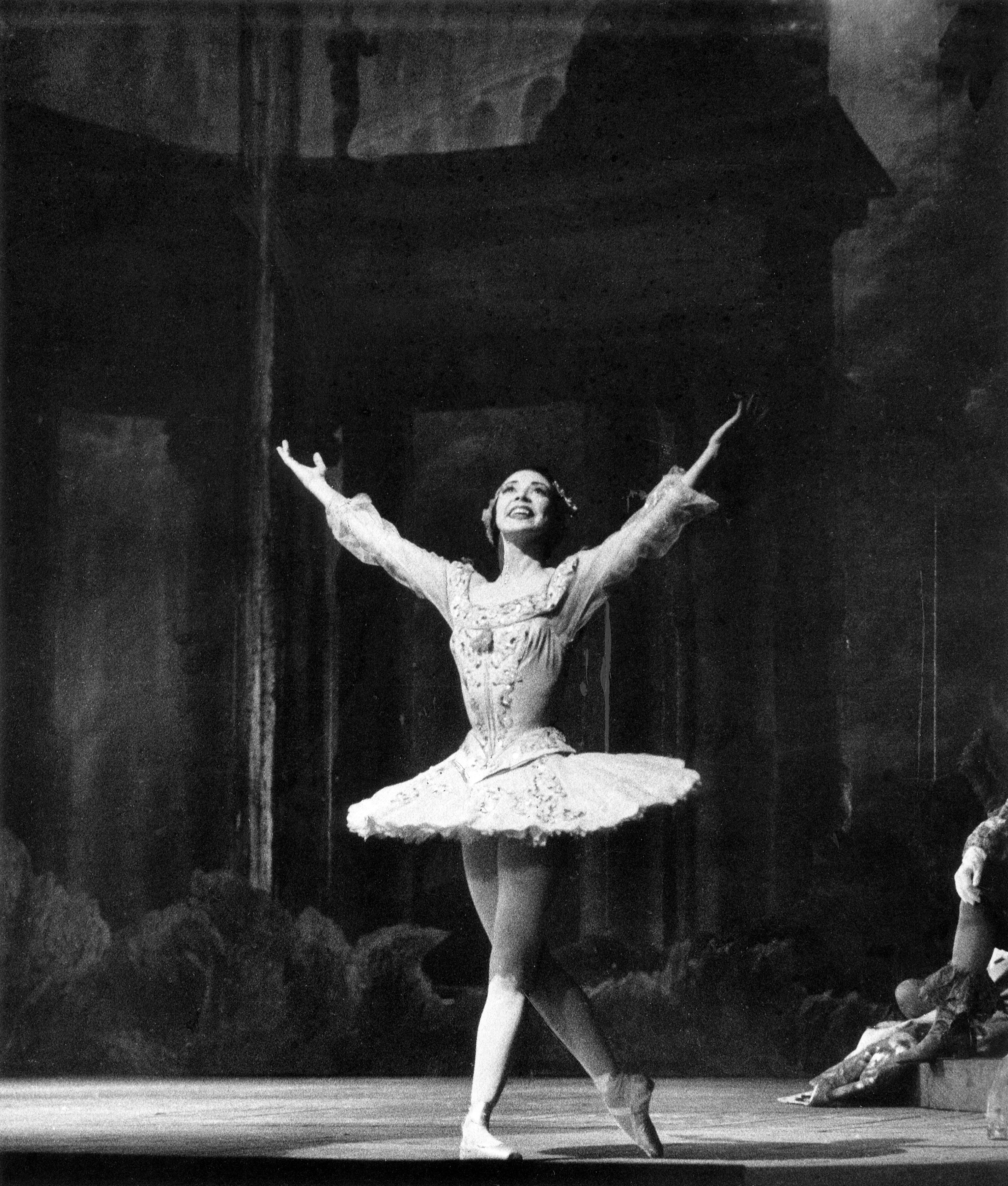

For us, the image of Les Sylphides brings to mind the notion of escapism, and as Rojo says this is one function of art that is “now certainly needed” (“The Art of Empathy”). Karen Eliot emphasises the importance of ballet’s ability to divert audiences’ attention away from everyday realities in her comments on the rising popularity of the 19th century repertoire during the War years:

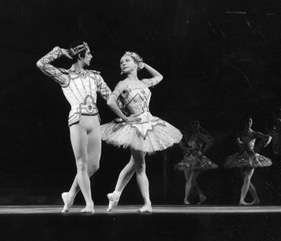

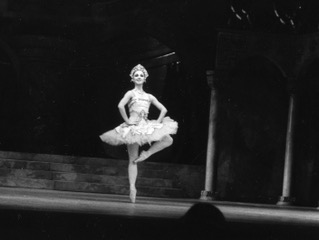

Unexpectedly, the multi-act 19th-century classical ballets that had earlier seemed old-fashioned and irrelevant during the war afforded both comfort and fascination to the diverse audiences who crowded theaters to see them …they opened up worlds of fantasy and colour, granting and audiences a few hours of visual sumptuousness that must have countered the gloom. (174)

However, in in addition to discussing art in terms of diversion, Rojo highlights its ability to help us to process situations we find ourselves in and to see them “from a different point of view”. For some people this is perhaps more likely to occur when watching and contemplating a different type of work. Known for the charm, vivacity and even frivolity of his choreographies in the 1930s, Ashton turned to more serious subject matter in the early 1940s in Dante Sonata, The Wise Virgins, The Wanderer and The Quest. In the words of Alexander Bland, “The international crisis seems to have opened up an emotional level in Ashtons’s artistic personality that had not previously been tapped” (59). Rich in symbolism, these allegorical ballets dealt with such themes as the conflicts between light and darkness, good and evil, the weaknesses of human nature, and the workings of the psyche (Vaughan).

In 2007 an exhibition at the Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms entitled Dancing through the War: The Royal Ballet 1939-1946 showcased the contribution made by the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet towards the War effort. This gave rise to dramatic broadsheet headlines paying tribute to the heroism and fighting spirit of the dancers: “As bombs fell, they danced on” (Crompton) and “Take that, Adolf!” (Mackrell). Seven years later, a BBC 4 documentary on British ballet in the War years was released: “Dancing in the Blitz: how World War II Made British Ballet”. As this title suggests, the focus this time was on the ways in which the conditions of war – or perhaps more accurately, the ways in which the government and those involved in ballet responded to those conditions – stimulated the development of ballet in this country in terms of the dancers’ performance and technical skills, the breadth of repertoire and the size and diversity of the ballet audience. Once again, the company that was the subject of this documentary was the Sadler’s Wells Ballet.

While it is understandable that what was to become Britain’s flagship ballet company would be the principal player in this narrative, we find these accounts problematic. It is not difficult to locate evidence that the Sadler’s Wells Company was one amongst many contributing to both the War effort and the development of the art form in this country. For example, Andrée Howard of Ballet Rambert provided “psychological realism” in her work, giving the audience insights into the “interior world” of her characters (Eliot 154-55). In contrast, Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet toured Britain throughout the War years staging “lavish full-scale ballets and playing in cinemas where theatres weren’t available, taking ballet to the people at a price they could afford” (“Blackout Ballet”). In fact, such was the prestige of International Ballet by 1951 that it was this company that was selected to perform at the opening of the Royal Festival Hall (Brown, I.). And there was an array of other, smaller companies that expanded audiences for ballet in Britain through their commitment, fortitude and imagination, offering them (civilians and those involved in military action alike) much needed comfort and distraction on the one hand, and intellectual inspiration and spiritual resonance on the other. These included Pauline Grant’s Ballet Group, Lydia Kyasht’s Les Ballets Jeunesse Anglaise, the Anglo-Polish Ballet, Les Ballets Trois Arts, the Ballet Guild and the Arts Theatre Ballet (Eliot 38).

Concluding Thoughts

“We are in the business of mass gatherings”. These straightforward and pragmatic words from Gillian Moore, Director of Music of the Southbank Centre (“The Future of Live Performance”) highlight both the long-term quandary imposed on the performing arts by lockdown and social distancing, and the way in which the present “war” differs so radically from the situation experienced by ballet companies during World War II, when gatherings of people from all walks of life in a variety of environments and venues became new captive audiences for ballet. With the emergence of new ballet companies there seems to have been constant work for dancers. We are not as confident about the employment situation faced by today’s freelancers working in ballet in all their various capacities – freelancers who, in our opinion, should be treated as “the crown jewels” of the industry (Thompson).

Let’s finish by drawing on some words by Karen Eliot from her peerless research on British ballet in the Second World War:

Personnel with the companies was fluid as the smaller groups disbanded and reformed under new direction, or as dancers moved from one organization to another. Throughout the period, dancers seem to have gamely carried on, moving through the daily regimen of their lives, making do with few resources, and mixing discipline and adventure. In their various missions, the companies created during the war highlighted ballet’s relevance to new and eager audiences; they demonstrated ballet’s potential to entertain as well as to offer aesthetic stimulus; and they testified to its viability as an art form with a distinct British identity. (38)

As we know, ballet in Britain now has a long-established identity, to which the activity of the War years made a pivotal contribution. However, since the beginning of lockdown, dancers, musicians, choreographers, film makers, amongst other ballet professionals, have engaged in new online endeavours in order to maintain both professional activity and their relationship with their audiences. They have offered us entertainment and aesthetic stimulus through their efforts, sometimes collaborating with colleagues from other companies. We have witnessed their sense of discipline, in particular through the sharing of online classes, and adventure in some of the enterprising videos we have relished. And we hope that new audiences will be attracted by the current hive of online activity in the world of British ballet.

But when those new audiences arrive, let’s not forget that the ballet world is an “ecology” comprising a plethora of establishments large and small, who are dependent on one another as well as on individual freelancers (Rojo “Tom and Ty Talk”). Let’s remember to recognise the contribution of everyone to the development of our art form and how it is helping us through the COVID “war”.

Dedicated to everyone working in British ballet, with heartfelt thanks for their steadfast commitment to the art form that we all love.

© British Ballet Now & Then

Next time on British Ballet Now & Then … Let’s not forget that this year English National Ballet is celebrating their 70th anniversary, so we’ll be thinking about its directors, repertoire and dancers, and the way the company has evolved over time.

Reference List

Abbot, Nick, and Carol McGiffin. What’s your Problem with Nick and Carol? Letting out gas on a plane. GlobalPlayer, 30 June 2020, http://www.globalplayercom. Accessed 11 July 2020.

Apter, Kelly. “Eve McConnachie: ‘Dance Films can add something to the movement because you can isolate moments and play with time’”. The List, 16 May 2019, https://list.co.uk/news/3595/eve-mcconnachie-dance-films-can-add-something-to-the-movement-because-you-can-isolate-moments-and-play-with-time. Accessed 18 July 2020.

“The Art of Empathy: Renée Fleming and Tamara Rojo on Creativity and Wellbeing”. The Female Quotient, 15 May 2020, https://www.facebook.com/FemaleQuotient/videos/172377800811211/?vh=e. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Bayley, Caroline. “The Highs and Lows of Working from Home”. BBC Radio 4, 2020, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2Mky6fvrChwCRd7fWQW8h9l/the-highs-and-lows-of-working-from-home. Accessed 19 July 2020.

Bellabrouwers. “The Quarantine Chronicles/Culinary Edition Pt1/2”. Instagram, uploaded 23 Apr. 2020, http://www.instagram.com/tv/B_VjsqSAme5/?igshid=1k1u993r4nt94. Accessed 5 July 2020.

“Blackout Ballet”. BBC Radio 4, 10 Dec. 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01p704k. Accessed 22 July 2020.

Bland, Alexander. The Royal Ballet: the first fifty years. Threshold Books, 1981.

Brown, Mark. “Geisha, Northern Ballet, review: ‘ambitious and accomplished’”. The Guardian, 15 Mar. 2020, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/dance/what-to-see/geisha-northern-ballet-review-ambitious-accomplished/. Accessed 31 May 2020.

Brown, Ismene. “Black-Out Ballet: the invisible woman of British Ballet”. The Arts Desk, 11 Dec. 2012, https://theartsdesk.com/dance/black-out-ballet-invisible-woman-british-ballet. Accessed 23 July 2020.

Courtney, Emily. “The Benefits of Working from Home: why the pandemic isn’t the only reason to work remotely”. FlexJobs, 1 June 2020, http://www.flexjobs.com/blog/post/benefits-of-remote-work/. Accessed 19 July 2020.

Craine, Debra. “Tamara Rojo: ‘It’s exciting for the dancers to have a date to work towards’”. The Times, 17 June 2020, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/tamara-rojo-its-exciting-for-the-dancers-to-have-a-date-to-work-towards-7d0067cfx. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Crompton, Sarah. “As bombs fell, they danced on”. The Telegraph, 5 Feb. 2007, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/dance/3662992/As-bombs-fell-they-danced-on.html. Accessed 31 May 2020.

—. “What will it take to save British theatre?”. Vogue, 11 June 2000, http://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/uk-theatre-crisis-coronavirus. Accessed 14 June 2020.

“Dancing in the Blitz: how World War 2 Made British Ballet (BBC Documentary)”. YouTube, uploaded 9 May 2019, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g5xxPY8er7E. Accessed 22 July 2020.

Edgerton, David. “Why the Coronavirus crisis should not be compared to the Second World War”. New Statesman, 3 Apr. 2020, http://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/2020/04/why-coronavirus-crisis-should-not-be-compared-second-world-war. Accessed 30 May 2020.

Eliot, Karen. Albion’s Dance. Oxford, 2016.

Frederick Ashton Foundation. “Fred step film”. YouTube, uploaded 27 May 2020, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbiMm96_H2M&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 5 July 2020.

Freedman, Lawrence. “Coronavirus and the Language of War”. New Statesman, 11 Apr. 2020, http://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/2020/04/coronavirus-and-language-war. Accessed 30 May 2020.

“Frontiers”, choreographed by Myles Thatcher. Scottish Ballet, 2019, http://www.scottishballet.co.uk/tv/frontiers. Accessed 18 July 2020.

“The Future of Live Performance”. Aspen Initiative UK,11 June 2020.

Hyde, Marina. “The horror of coronavirus is all too real. Don’t turn it into an imaginary war”. The Guardian, 7 Apr. 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/07/horror-coronavirus-real-imaginary-war-britain. Accessed 23 May 2020.

Hutera, Donald. “Geisha Review – supernaturally charged and unexpectedly touching”. The Times, 16 Mar. 2020, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/geisha-review-supernaturally-charged-and-unexpectedly-touching-g3xgrf557. Accessed 31 May 2020.

Mackrell, Judith. “Take that, Adolf”. The Guardian, 14 Feb. 2007, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2007/feb/15/dance. Accessed 22 July 2020.

Mendes, Sam. “How we can save our theatres. Financial Times, 5 June 2020, http://www.ft.com/content/643b7228-a3ef-11ea-92e2-cbd9b7e28ee6. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Monahan, Mark. “‘How should everyone keep fit during lockdown? Just put on some music and move!’”. The Telegraph, 30 Apr. 2020, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/dance/what-to-see/should-everyone-keep-fit-lockdown-just-put-music-move/. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Donne, Mark. “PERFORMANCE: Mute”. BalletBlack. Performed by Circa Robinson, 2016, https://balletblack.co.uk/bb-on-film/. Accessed 18 July 2020.

Pong, Beryl. British Literature and Culture in Second World Wartime: for the duration. Oxford UP, 2020.

Rosado, Ana. “These Ballet Dancers are Keeping Limber under Lockdown”. 7News, 20 Apr. 2020, https://7news.news/these-ballet-dancers-are-keeping-limber-under-lockdown/. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Roy, Sanjoy. “Northern Ballet: Geisha review – potent fusion of romantic dance and Japanese horror”. The Guardian, 15 Mar. 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/mar/15/northern-ballet-geisha-review-grand-theatre-leeds. Accessed 31 May 2020.

Sanderson, David. “Ballet dancers need three months to get back in step after lockdown”. The Times, 15 June 2020, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ballet-dancers-need-three-months-to-get-back-in-step-after-lockdown-vnrhlw6z7. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Simpson, Edward. “Solving JN-25 at Bletchey Park:1943-5”. The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park, edited byRalph Erskine and Michael Smith, Biteback Publishing, 2011.

Thompson, Tosin. “The real ‘crown jewels’ of the arts? An unprotected freelance workforce”. The Guardian, 22 July 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/jul/22/the-real-crown-jewels-of-the-arts-an-unprotected-freelance-workforce. Accessed 25 July 2020.

“Tom and Ty Talk: ‘Ballet is honest’ with Tamara Rojo”. Tom and Ty Talk, 19 June 2020, https://pod.co/tom-and-ty-talk. Accessed 19 July 2020.

@uk_aspen. “It’s not often”. Twitter 11 June 2020, 6:28pm, https://twitter.com/uk_aspen/status/1271132243000471555?s=20.

Vaughan, David. Frederick Ashton and his Ballets. Rev. ed., Dance Books, 1999.

Weiss, Deborah. “English National Ballet – 70th Anniversary Gala – London”. DanceTabs, 20 Jan. 2020, https://dancetabs.com/2020/01/english-national-ballet-70th-anniversary-gala-london/. Accessed 31 May 2020.

“Wartime Entertainment”. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2016.

“Where We Are: An original film by Alexander Campbell and Anthoula Syndica-Drummond”. YouTube, 11 June 2020, https://youtu.be/gN8mjOLU9Gg. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Wiegand, Chris. “Dancing in the streets: Royal Ballet stars rock to new Rolling Stones song”. The Guardian, 8 June, 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/jun/08/royal-ballet-rolling-stones-mick-jagger-living-in-a-ghost-town. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Wulff, Helena. Ballet Across Borders. Berg, 2001.