We are excited. This year has seen so many performances cancelled, new productions put on hold, new choreographies postponed. And now, over the weeks leading up to Christmas, English National Ballet are releasing five brand new dance films …

Take Five Blues

Photos: English National Ballet in Take Five Blues, a film by Shaun James Grant, choreographed by Stina Quagebeur © English National Ballet

Choreography: Stina Quagebeur

Filmmaker: Shaun James Grant

On a gloomy, overhung Thursday afternoon we are eager to see some positive signs of hope, even if only on our screens.

Take Five Blues begins with some of our favourite dancers entering the space … casually, as if in anticipation of the energy to come: Aitor Arietta, a long-time favourite; Fernando Carratalà Coloma, whom we admired so much as the Messenger of Death in Song of the Earth; Rentaro Nakaaki, who impressed us so much last year in Emerging Dancer; Katya Kaniukova, sassy as ever, and Shiori Kase with her joyous turns and luminous presence.

Choreographer Stina Quagebeur wants it to feel like we’re in the room with the dancers, and in fact we are reminded of watching class. The visible energy. The audible energy. Moments of relaxation to take breath. The spurring on of colleagues. Personalities gleaming through the movement. But the globes of soft light hanging over the dark stage space evoke an ambiance of a different ilk.

There is a serendipitous moment when Fernando Carratalà Coloma and Henry Dowden reach the height of a jump in complete synchrony.

Unwittingly our lecturer hats are donned and we start to admire the structure of the work: individual dancers merge into clumps of synchronous movement – they scoop down and reach forward, scoop and reach in an easy rhythm – and then peel off one by one. Breathtaking virtuosic display is juxtaposed with movements in slow motion. Roaming camera angles lend added texture to the patterns and rhythms of the choreography.

But ultimately we are captivated by the buoyant sway of the dancing to the familiar tones and rhythms of Paul Desmond’s Take Five and Bach’s Vivace in Nigel Kennedy’s ebullient arrangement. We laugh as all the male dancers collapse to the floor at the end.

The gloom of the Thursday afternoon is gone.

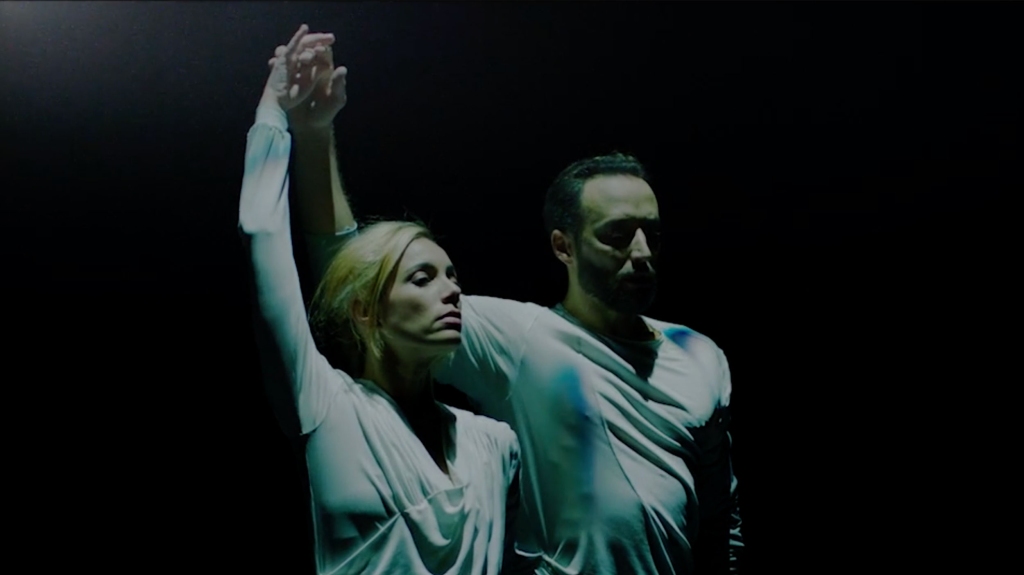

Senseless Kindness

Photos: Isaac Hernandez, Francesco Gabriele Frola and Alison McWhinney in Senseless Kindness a film by Thomas James with choreography by Yuri Possokhov © English National Ballet & Emma Hawes and Francesco Gabriele Frola in Senseless Kindness a film by Thomas James with choreography by Yuri Possokhov © English National Ballet

Choreography: Yuri Possokhov

Filmmaker: Thomas James

From the trailer of Senseless Kindness we know that the tone is quite different from Take Five Blues. Here darkness reflects a more melancholy and sombre mood. While the whirling turns in Take Five Blues were exuberant in spirit, here Isaac Hernández spins himself into a vortex of frantic energy.

Monochrome hues, shafts of light steaming through the darkness create atmospheric spaces evoking sites of conflict and flight, fear and anxiety; and sites of momentary peace and joy.

The two couples, perfectly matched, conveying the sense of being connected by family, move fluidly together from shape to shape like kinetic sculpture. Unison intensifies the sense of togetherness, but then the couples find their own spaces to express their own identities.

Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 1 catches at us with the tension of its edgy strings and percussive keyboard, giving rise to angular, staccato movement for the male dancers, performed with urgent attack and dramatic intensity. Lyrical passages bring forth movements that melt into slow motion and blurred lines, like memories passing across the mind. From time to time the dappled faces emerge and the camera hovers over tenderness, longing, sadness. But then a smile crosses our lips at the warm playfulness of a pas de bourrée.

Speaking of the meaning of his work as a reflection of life, choreographer Yuri Possokhov muses: “so many negative things and so many positive things at the same time” (documentary 5:10-5:14).

Isaac Hernández’ vortical spins swiftly unravel into an ecstatic attitude reaching for the sky.

In Senseless Kindness everything is shadows and light.

Laid in Earth

Photos: James Streeter and Jeffrey Cirio in Laid in Earth, a film by Thomas James, choreographed by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui © English National Ballet

Choreography: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

Filmmaker: Thomas James

Twenty-four hours on and we are still haunted by Laid in Earth. Images of a Stygian forest and lake flit through our heads. The underworld has been recreated for us, inhabited by four beings who twist and curl like the gnarled branches surrounding them. Sometimes their limbs mutate into branches. Sometimes they fuse spookily with the forest itself, their bodies becoming sites for forest growth. Jeffrey Cirio’s character rarely moves far from the ground: he slides and spins seamlessly over it, sinks softly into it, allowing gravity to release him down. Mesmerizing costumes and make-up seal the oneness of dancers and their environment.

Erina Takahashi’s distilled energy gives an eerie glow to her being, drawing us to her as the central figure. She almost takes the hand of her shadow Precious Adams, but they seem wary. They reflect one another in the dark waters. James Streeter and Jeffrey Cirio mirror one another on the dark ground. In the duet Erina Takahashi and James Streeter coil around one another in a dance of sorrow.

Laid in Earth brings Giselle to mind – the Wilis inhabiting the shadowy forest, their hems damp from the water of the lake above which they hover, and maybe from the early morning dew as they dissolve into the morning’s mist. Hearing Dido’s plangent tones “Remember me”, we recall the rosemary branch that transforms Giselle into a Wili.

If everything in Senseless Kindness is shadows and light, then everything in Laid to Earth is shadows and darkness.

Echoes

Photo: Fernanda Oliveira and Fabian Reimair in Russell Maliphant’s Echoes a film by Michael Nunn & William Trevitt © English National-Ballet

Choreography: Russell Maliphant

Filmmakers: Michael Nunn & William Trevitt

Over the weeks we have noticed that all the new choreographies have different casts, so every week we are seeing different dancers. For us it feels like a big bonus to see a range of dancers from the Company (not to mention its egalitarian spirit). But it’s also exhilarating to watch the dancers being challenged by movement styles that are unfamiliar to them. This is noticeable to us this week in Russell Maliphant’s Echoes. In the documentary we particularly enjoy Fabian Reimar and Fernanda Oliviera talk about both the challenges and the satisfaction of working with Maliphant in the studio with his task-based approach to the creative process, the groundedness of his choreography, the liquid dynamic of his movement – “like the ocean”, as Fernanda says (1:00-1:02).

Fernanda and Fabian dancing together is like a pas de deux of the ocean waves. Moving seamlessly together as one, waves of motion repeatedly merge into one another.

Along with Fabian Reimar, Isabelle Brouwers is a dancer whom we admire greatly. Both can bring vibrant drama to the simplest of movements. This we have witnessed in Akram Khan’s Giselle when they perform the Landlord and Bathilde respectively. In Echoes we witness it once again as Fabian looms on the screen with his rich and resonant presence.

When Isabelle dances in classical pas she radiates an incandescent glow. In Echoes her glow is hushed, softly diffused, though ever present, subsumed in the hypnotic swirling of the group.

Again and again we note the soft passive weight of the dancers. Then the movement accelerates, becoming electrifying as the dancers swiftly free flow between heavier passive weight and strong active weight. The dance reaches its whirling crescendo.

As the piece moves to a close, alone on the stage, Junor Souza spirals continuously, an echo of what has passed that reverberates into the future as the image hovers in our minds …

And once again we leave our screen with optimism, not only about the survival of ballet, but even about its potential revival.

Jolly Folly

Photos: English National Ballet in Jolly Folly, a film by Amy Becker-Burnett, choreographed by Arielle Smith © English National Ballet & Francesca Velicu, Ken Saruhashi and Julia Conway in Arielle Smith’s Jolly Folly a film by Amy Becker-Burnett © English National Ballet

Choreography: Arielle Smith

Filmmakers: Amy Becker-Burnett

Boxing Day. Jolly Folly was released almost a week ago, but anything with the name Jolly Folly just seems to be made for Boxing Day. And we’re told that this piece is reminiscent of “Old Hollywood”, and what else is Boxing Day for but whiling away the hours, spinning out the nostalgia over well loved classic movies? The trailer has already revealed fantasy locations, and a single row of dancers scooting away from the line, one by one, in precise canon. Busby Berkeley comes to mind …

We chuckle at the of irony in this 16-minute dance film being divided into three acts – that iconic structure that we tend to associate with the grandeur and scale of the late 19th century classics and the “full-length” dramas of Kenneth MacMillan. Each act is announced by the flickering sound of a film projector …

Quizzical looks and quirky walks on the black-and-white screen remind us of Charlie Chaplin. We’re not well versed in Chaplin’s films, but the dim street lighting of Act I makes us think of the waterfront in his 1931 City Lights, while the boxing ring shenanigans are an unmistakable reference to the prize fight from the same film. Dinner jackets, white tie and tails worn by the dancers are all part of the “Gentleman Tramp’s” wardrobe.

From gentle-smile to laugh-out-loud, the humour is enhanced by Arielle Smith’s use of the score – the Klazz Brothers’ Classic Meets Cuba. Joseph Caley and Ken Saruhashi sashay and pirouette to “Cuba Danube”. All nonchalance, they press up and sway from side to side in a backbend bridge, then leap and cartwheel over one another to the reworking of Johann Strauss II’s “The Blue Danube”.

Act II brings us an exquisite fulfilment of our Boxing Day thinking, as the chimes of the Sugar Plum Fairy morph into a paradoxically unsettling accompaniment to a world of grey clouds and craggy rocks, where the dancers strut across the space, hands in pockets, in a slightly menacing way, almost as if we’ve strayed into film noir territory.

But with ever-changing vistas, coat-tails flying in elegant chaînés and suspended arabesques, Act III takes us back to the safe shores of Busby Berkeley and Fred Astaire. Dancers skitter lightly across the space to the whimsical rendition of Mozart’s speedy “Rondo à la Turque”. Jolly Folly ends in a gleeful final pose.

Epilogue

We were sorely disappointed. Having booked our tickets to see these new choreographies onstage, we were “only” able to watch them on our screens. But we were wrong … or at least half wrong …

In the end we discover that it’s not “only” on our screens. These films are something to be treasured as a development in ballet making and ballet performance – they are not simply something to fill the gap left by the lack of live performances.

Nonetheless, we can’t wait to see them live on the theatre stage. That moment can’t come too soon.

Wonderfully audacious and dynamic description of the way ballet in Britain has managed to turn around the restrictions of lockdown into an unparalleled display of innovation!!! Brilliant! Congratulations for the hopefulness you give us all!

LikeLiked by 1 person