It’s been a long time coming. After being cancelled in both the spring and the autumn of 2020, Akram Khan’s Creature for English National Ballet has finally arrived on the stage.

In preparation for watching Creature we have familiarised ourselves with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and wracked our brains for memories of studying Georg Bűchner’s 1837 Woyzeck at university. To our consternation we have discovered that our image of Frankenstein’s Creature was totally askew, being associated in our minds with the horror genre of literature and film, and consequently with gratuitous savagery and cruelty. Of course, both of these literary works deal with savagery and cruelty, but the vulnerability and pathos of Frankenstein’s “Monster” is something that had passed us by until now …Having watched the miniseries (Connor, 2004) and the National Theatre’s streaming of Danny Boyle’s 2011 production last year, and subsequently read the novel, our eyes have been opened …

As usual, English National Ballet have produced teasers, and videos discussing aspects of the work and preparations for the premiere.

The extract with Jeffrey Cirio in the Arctic station dancing to Richard Nixon’s voice sends chills down our spine:

Because of what you have done

Because of what you have done

Because of what you have done

Nixon’s words, delivered to the Apollo 11 Astronauts in 1969, were intended as a message of pride and peace: “I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of what you have done … it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquillity to earth”.

But in front of us the movements of Khan’s Creature are spasmodic, fragmented, jittery, oscillating constantly between childlike curiosity and pride, fear and pain. This Creature is a combination of Frankenstein’s Creature, and Woyeck, the impoverished and degraded military barber who submits himself to medical experiments, such as the indignity and pain of consuming a diet of peas alone, in order to earn some much-needed extra cash. Juxtaposed to the Creature’s movements Nixon’s triumphant words take on a sinister meaning: “Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man’s world”. We hear echoes of the repugnant arrogance of Victor Frankenstein and the Doctor in Woyzeck, arrogance that results in such cruel behaviour as to drive the victims of their cruelty to brutal, murderous acts.

From the 19th century classics to Khan’s own works for English National Ballet, we know the power of group movement: the menace of Jean Coralli’s Wilis in Giselle (1842); the sheer transcendental beauty of “The Kingdom of the Shades” from Petipa’s 1877 La Bayadére; Khan’s human waves of mourning in Dust (2014). Now we catch glimpses of such power again in the snippets of Creature that we’ve seen: a brigade of soldiers travelling swiftly through the space, consuming it through frequent changes of direction, attacking it through repeated thrusting and pulling movements as if they’re digging, mining the earth, hauling great weights. Machine-like in their precision and strength. We discover later the weakness hidden beneath such strength, the extent to which unison can be used to convey conformity—conformity, and fear of being different, of not belonging.

The opening scene of the ballet is dominated by Creature’s solo to Nixon’s words, and over the evening it transpires that this is the key to the whole work. The Soldier Astronauts enter the stage with huge slow-motion steps, pressing their way through the atmosphere to invade the space. Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” passes through our minds.

Like labourers in a penal colony, they continue with their relentless thrusting and hauling. At other times they slither, slide and wriggle like animals, or pay obeisance to the Major, the symbol of ultimate control and power in the work. Like automatons, their movements are frequently fragmented, stiff, constricted. Fear ensures they seldom step out of line. Creature suffers torture as the guinea pig of scientific experimentation. Fear ensures that the soldiers fail to show him the empathy that would make them truly human: they seem to have been robbed of every human emotion save the fear of non-compliance. We feel the looming presence of Solzhenitsyn, Orwell, Kafka …

Bűchner’s Doctor, so full of his own importance, has become a liminal figure in Creature. In her behaviour the Doctor shows how failure to show empathy is a process of erosion. Her behaviour towards Marie, Creature’s keeper, and occasionally even towards Creature himself, demonstrates her potential for empathy; but her responses to the Major show that her status is too precarious for her to be able to indulge in such humane sentiments.

The work is quite desolate where human kindness, feeling or responsibility are concerned. Although there are exceptions.

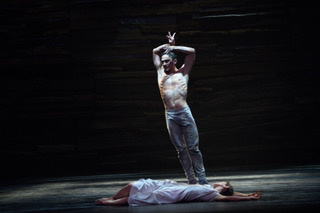

Creature performs tender and playful duets with his friend Anders and with Marie—here unison suggesting friendship, mutual understanding and affection, while free flow in the movement and music conveys a rare feeling of joyfulness.

Like Frankenstein’s Creature, he is eager to learn from Anders and Marie; like Frankenstein’s Creature, he is longing to give as well as to receive affection.

But the abuse of power seeps through the very pores of the work, and the performance moves to a close literally on a different note to those we’ve heard before, as we hear the tones of sacred music accompanying the sight of Creature holding the lifeless body of Marie in his arms. But he has not killed Marie: unlike his literary predecessors he has killed no one. He has in fact attempted to protect her from the Major’s sexual assault. Creature and Marie pay the price for not complying, for being different: she for resisting the advances of the Major, and for daring to show some empathy towards Creature; he for never quite mastering the steps, never quite understanding the patterns to which he is required to adhere.

As the Soldiers depart from the collapsing research station in search of a new project, new places to conquer, Creature repeats some of his dance from the start of the ballet, only this time in the presence of Marie’s dead body. He mimics walking forward with a rifle in his hand, as if he is a “forgotten man” from Al Dubin’s “Remember My Forgotten Man”, the extraordinary culmination of Busby Berkely’s Gold Diggers of 1933:

Remember my forgotten man,

You put a rifle in his hand,

You sent him far away,

You shouted “hip-hooray!”,

But look at him today.

Just as this musical number depicts how World War I soldiers were abandoned by the state after they had served their purpose, the climax of Creature depicts the two protagonists abandoned in the disintegrating research hut. They have served their purpose.

As Creature dances with Marie’s limp body, we realise that we have already seen this image. In the first few moments of the work. We realise that Marie’s rape and murder have both taken place downstage left, where the story began in darkness, save the glow emanating from Marie’s cleaning bucket, a prop that clearly symbolises life and rebirth through its connections with light and water. The terrifying realisation dawns on us that the cycle of events that have played out over the last two hours are all too likely to repeat themselves …

Over the course of the evening we have heard Nixon’s words repeated, disintegrate into a coughing fit, and become increasingly distorted, until their final incomplete, but telling, iteration uttered by the voice of Andy Serkis, as if he is gasping his final breath … “Because of what I …”. The prominence of Nixon’s proclamation, combined with the corps de ballet’s conquering of the stage space, and the persistent pointing upwards towards the sky, makes it clear to us that the makers of Creature are concerned not only with “man’s inhumanity to man”. If space has become part of “man’s world”, the implication is that planet Earth is already “man’s world” and consequently subject to the whims and desires of human beings, no matter what the cost to the future of the world and its population. The volume and raw insistence of Vincenzo Lamagna’s sound score, matched with synchronised movement, means there is no escape from a visceral response to the stage action. We are reminded in no uncertain terms that we are all a part of this tale: “We’re all part of climate change. We all contribute to CO2 – we all drive cars, we fly, we all waste food, so we’re all part of it.” (Khan, “Akram Khan: Dancing Creature”).

And then there’s the cleaning. Of course there’s cleaning—we’re in a scientific lab—but the relentless mopping, wiping and scrubbing performed by Marie, Andres and Creature gives us the feeling that we are trying to subjugate our environment, tame it, erase its essence, so that we can exploit it to our heart’s desire. It reminds us of Norbert Elias’ The Civilising Process (1939).

The walls are cleaned, the floor is cleaned, but most importantly, the table is cleaned. The Major mounts the table, shimmering with Olympian ease. From here he is panoptic master of all he surveys. But the table is also a world for Creature and Marie to explore together, as they move around it, over and under it, and dance together on its surface.

Through the course of this tale layers of meaning have carved meandering paths through our minds. In the final moments the political and personal converge in a potent climax. Like the words of Nixon, the research hut itself is disintegrating—a message for us all to take more care of our environment—while we witness the unbearable pain of Creature as he holds the corpse of Marie in his arms, his aloneness palpable.

We remember Frankenstein’s promise to make a female companion for his creation to assuage the Creature’s devastating loneliness, the promise that he breaks in the most heinous way by tearing her to pieces before even having finished constructing her. We remember Mary Shelley’s Last Man (1826), a startling prediction of our times. We realise that our hands have been clenching throughout the evening.

As we leave the theatre our minds are replete to bursting with images. So many images, it’s impossible to imagine there won’t be plenty for each member of the audience, no matter what their background, experience in ballet or expectations.

The following morning our minds are still jangling. Akram Khan wants his audience to “… feel a sense of the work; I don’t want you to see sense in the work” (“Free Thinking” 9:38-9:42).

We have gained a sense of Creature. We look out of the window at the garden and wonder where exactly we ourselves fit into Creature’s tale.

We would like to thank our friends Philippa Burrows, Susie Campbell and Paul Doyle for stimulating conversations about Creature, which have undoubtedly found their way into this post.

© British Ballet Now and Then

References

“Creature: The Army (extract)”. English National Ballet, 2021, www.ballet.org.uk/production/creature/.

“Creature: Because of What You Have Done (extract)”. English National Ballet, 2021, www.ballet.org.uk/production/creature/.

Khan, Akram. “Akram Khan: Dancing Creature”. Interview by Maggie Foyer. Dance ICONS, Sept. 2021, www.danceicons.org/pages/index.php?p=210826140840.

—. “Free Thinking: Belonging”. Produced by Tim Bano, BBC Sounds, 16 Sept. 2021, www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000zl33.