Despite its sumptuous score by Alexander Glazunov, and Marius Petipa’s glorious choreography, the 1898 Raymonda is one of the 19th century classics that has rarely been performed in its entirety by British ballet companies. Although there is a tradition of staging excerpts from the ballet, generally from the final act wedding celebrations of the eponymous Raymonda, English National Ballet’s announcement of a new full-length production of the ballet came as a surprise to us.

Perhaps one of the reasons this ballet has up until now not joined the list of beloved 19th century classics in this country is the vagaries of its plot, which has been described as “foolish” (Anderson 64), “senseless” (Tomalonis, “The Mysteries”), “boring” (Sulcas), and “Devoid of suspense and romantic drama, … a mere pretext for a cornucopia of dancing” (Khadarina, “Mariinsky Ballet”). While ballets such as Giselle (Coralli/Perrot, 1841), The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890) and Swan Lake (Petipa/Ivanov, 1895) can be perceived as divorced from contemporary life, their narratives and choreography are nonetheless replete with symbolic meanings with their tales of betrayal, remorse and revenge to forgiveness, redemption and renewal. Tamara Rojo, Artistic Director of English National Ballet, who commissioned Akram Khan’s 2016 reimagining of Giselle, says “The beauty of these classics, whether it’s Giselle or Swan Lake, is that the core theme is timeless, that even though it was specific to that time, it is still relevant today” (01:35-01:53). Evidently the same claim cannot be made in the case of Raymonda.

Devised by Countess Lydia Pashkova, a society columnist and novelist, the libretto of Raymonda is a tale of mediaeval romance set in Provence at the time of the Fifth Crusade. The valiant French knight Jean de Brienne, who is betrothed to the Countess Raymonda, slays Abderrakhman, the Saracen rival for Raymonda’s love. From this slight pretext, Pashkova and Petipa created a ballet of three acts made up of multiple tableaux, and famously culminating in the Hungarian style nuptials of Raymonda and Jean de Brienne.

Although, as far as we can tell, the character of Raymonda herself is not based on a real historical, both Raymonda’s fiancé, the French Knight Jean de Brienne, and King Andrei II of Hungary, who attends the wedding, are based on historical leaders of the Fifth Crusade (1217-1221). However, as critic Alexandra Tomalonis points out, it’s not entirely clear what either of these Crusaders or Abderrakhman are doing in Provence, so far from the action in the Middle East (“The Mysteries”). The list of characters attached to the original libretto identifies Raymonda as the “Countess de Doris”, and the action of Acts I and II takes place inside and around the Countess’ castle, before moving to her Fiancé’s castle for the Act III wedding (Pashkova). No parents are listed, but Raymonda does have an Aunt, the Canoness Sybille, and the House of Doris is protected by a mysterious “White Lady”, despite the fact that the name Raymonda itself means “wise protector” (“Raymonda Origin and Meaning”). While some of this is quite confusing, we find it interesting that the House of Doris is indisputably depicted as a matriarchal establishment led by women very aware of their responsibilities.

Where Raymonda’s Aunt and the White Lady are concerned, this notion of responsibility is clearly evident from the start of the ballet. In the opening scene the Canoness Sybille reprimands Raymonda’s attendants for their indolence, warning them against punishment from the White Lady if they do not heed her words and consequently fail in their duties. In the second scene the White Lady reveals the impending danger of Abderrakhman’s arrival to Raymonda in a vision. Of course, far more interesting to us is how the concepts of duty and responsibility manifest themselves in the person of Raymonda herself.

But in a sense, herein lies the problem. Choosing a life partner is the stuff of 19th century ballet. Raymonda’s predecessors Giselle (Giselle, 1841), Kitri (Don Quixote, 1869), Nikiya (La Bayadère, 1877) and Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty, 1890) all follow the dictates of their heart. Admittedly the results are sometimes disastrous, but at least they have made their own choice. But who chose Jean de Brienne for Raymonda? He is described as her “beloved” (Pashkova 401), and Raymonda is “delighted” at the thought of him (397, 399). On the other hand, she rejects Abderrakhman “indignantly” (399) and “contemptuously” (400), implying a more intense emotion towards the Saracen, despite, or perhaps because of, his “flaming passion” (Khadarina, “Mariinsky Ballet”), “sensual presence” (Smith) and “seductive power” (“Alexander Glazunov”). Does Raymonda seriously feel no attraction towards him? It seems to us, the lady doth protest too much.

As we were doing our research on Raymonda, watching performances and re-reading the libretto, we were reminded of dance historian Sally Banes’ discussion of Mikhail Fokine’s The Firebird, a ballet which premiered twelve years after Raymonda, under the aegis of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The way in which Banes interprets the contrast between the two female protagonists of The Firebird strikes a chord with us in connection with the two male protagonists of Raymonda.

Here is a tale based on Russian folklore in which the hero Prince Ivan forms relationships with two vastly different female characters: the Princess, or Tsarevna, and the Firebird herself. While Ivan is attracted to both characters, they represent two opposing images of womanhood. Banes describes the Princess in The Firebird as “demure” (97), “nice” (98), “virginal” (98), and “a ‘true’ Russian maiden, an ideal of racial purity and national superiority” (99). In stark contrast, she describes the Firebird as the polar opposite: “oriental, sexual, seductive, both powerful and submissive, she is everything desirable the ‘nice’ Russian Tsarevna cannot be” (98). To us the Firebird seems to fit the mould of the Muslim Abderrakhman, who can be perceived as submissive as well as “oriental, sexual, seductive, … powerful”. In the original libretto, for example, he suffers “despair” at Raymonda’s rejection of his gifts to her (398); he is unable to focus on the stage entertainment, so “lost in dreams of Raymonda” is he (398). Dance writer Oksana Khadarina goes further in her review of Konstantin Zverev’s performance of Abderrakhman, who in his “agonizing heartbreak … was as pitiful as he was poignant, inspiring both empathy and regret” (“Elegance & Exuberance”). An opposing image of manhood is portrayed in the figure of Jean de Brienne. Olga Makarova has described him as “refined and classical”, and it is perhaps the restraint suggested by these words that has caused the phrase “milquetoast lad” to be used as a description of Raymonda’s fiancé (Dix). Would Banes have referred to him as “nice”, like the “‘nice’ Russian Tsarevna” from The Firebird, we wonder? It goes without saying that both Prince Ivan and Raymonda favour the safe option for their marriage partners, that is, the racially pure but bland over the “dangerously attractive” (Sulcas).

So we return to our idea of Raymonda’s sense of duty and responsibility being a problem for us. The patent inevitability of Raymonda’s union with the safe option seems to rob her of personal agency over her own destiny: the lack, or denial, of any attraction towards the incandescent Abderrakhman smacks of docility, even submissiveness. This lack of agency is exacerbated at the climax of the narrative. At this point, far from Raymonda being given a choice (even the choice to marry the partner who has presumably been selected for her), King Andrei insists that the two rivals fight a duel. Khadarina hits the nail on the head: “The winner (Jean de Brienne) gets the fair lady” (“Elegance and Exuberance”). Raymonda may be a countess, but to all intents and purposes, where finding a life partner is concerned, she is reduced to a mere trophy.

Despite all these concerns regarding Raymonda’s lack of agency, we cannot but agree with critic Tomalonis’ assessment of the ballet, after she has analysed the anomalies of the libretto in some detail:

Another way to look at it is that “Raymonda” can be seen as a great gift to us: it’s living dance history. “Raymonda” received its premiere two months before Petipa’s 80th birthday, and everything he knew about ballet and its history is contained in it. (“The Mysteries”)

And here we find another striking connection with Banes’ writing. In her consideration of female agency Banes shifts the focus away from the narrative and “marriage plot” as she calls it, and onto the stage action. Let’s look at what she has to say:

The issue of looking at plot in relation to performance has enormous consequences for interpreting representations of women in choreography. The plot may verbally describe the female character as weak or passive, while the physical prowess of the dancer performing the role may saturate it with agency. Thus, even dances with misogynist narratives or patriarchal themes tend to depict women as active and vital. (8-9)

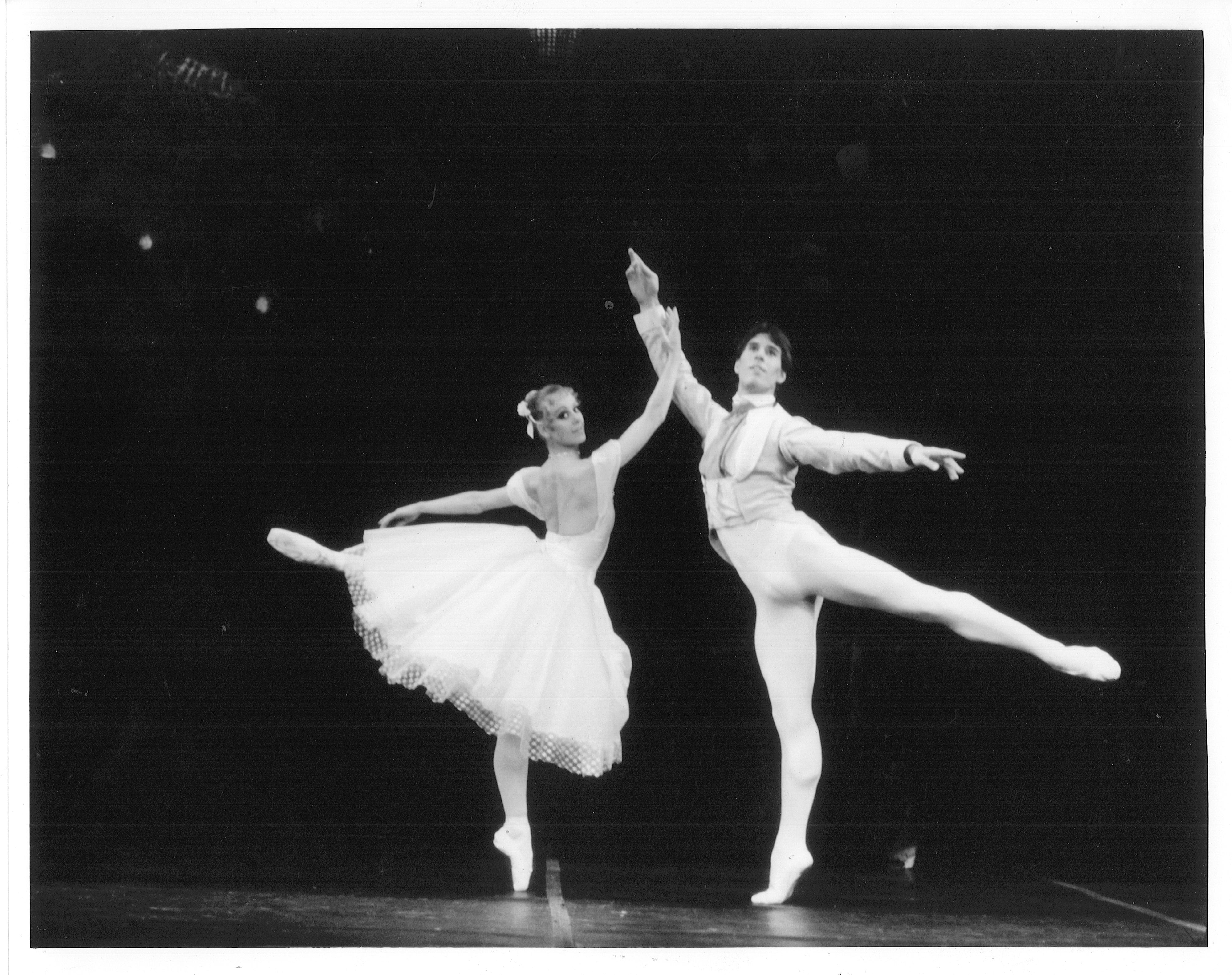

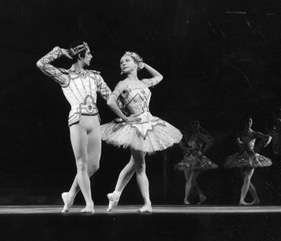

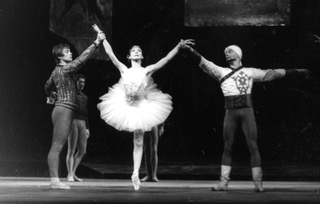

The opportunity to “saturate” the choreography with agency is particularly noticeable in Raymonda. In his “great gift to us” (Tomalonis, “The Mysteries”), Petipa gave an even greater gift to the creator of the eponymous role, Pierina Legnani, that is, no fewer than five solo variations, suggesting a range of moods, and a complexity and boldness of character belied by the narrative. So now we’re going to outline these dances to give a sense of the richness and variety of Raymonda’s dances and the way in which they provide a platform for a ballerina to display her “physical prowess”. For this outline we’ve used the recording of Sergei Vikharev’s 2011 reconstruction of the ballet for La Scala with Olesya Novikova in the ballerina role, in an attempt to reflect as accurately as possible the original choreography.

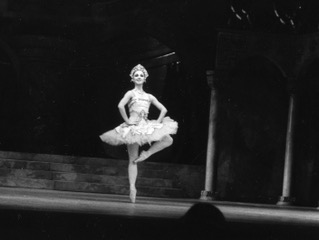

The variations start with a pizzicato solo involving lots of pointe work—piqués, hops and brushes—mirroring the delicacy and playfulness of the music. The Scarf Solo (named Fantaisie in the original libretto, and also known as the Harp, Shawl or Veil Solo Variation) is more expansive, incorporating bolder movements, and far-reach leg gestures such as arabesques and developpés, highlighted through the fine articulation of contrasting smaller, subtler movements. The “Dream Scene” solo is characterised by grand legato movements, such as grands ronds de jambe, and a series of renversés travelling across the stage, followed by a closing section of unexpected speed and vivacity. Undisguised virtuosity marks the penultimate solo with its pirouettes, fouettés, piqués turns en dehors and en dedans, and chaînés, with a magnificent highlight of entrechats quatres sur pointe. The final, and most famous, variation oozes virtuosity of a different order, in the sophisticated use of the upper body: the lush épaulement, curves and tilts of the torso, and the fluid rotation of the arms as they carve their way through the various pathways of the kinesphere.

Throughout these dances Raymonda commands the stage, exerting a level of agency denied her by the libretto that bears her name. And now we turn to a third aspect of Banes’ discussion (8-11), one with which we are very familiar, that we wrote about in our first Giselle post, in fact. This is the importance of each individual ballerina’s shaping of the choreography, for example, in terms of rhythm, use of space, line, articulation and dynamics.

To illustrate this idea we have selected a few examples that you can check out online. Two of the Raymondas who caught our eye particularly in the Scarf Variation were Maria Alexandrova and Olga Smirnova of the Bolshoi Ballet. When reviewing Smirnova’s debut, critic Janet Ward marvelled at the “breathtaking” harmony of her movement, created through a combination of “musicality, exquisite line, elegant bearing, supple back, and beautiful arms”. This harmony was unmistakable to us in her performance to Glazunov’s harp music, in her accentuation of classical line in her developpés, arabesques and attitudes, and her use of the veil to complement the purity of her lines. On the other hand, Alexandrova seems to be more playful in her approach to the choreography: she gains visible pleasure from swaying and bending her body, rippling and waving her arms to give life to the scarf, sweeping it close to her face and holding it high with her left hand as she bourrées. Therefore, even through this one single dance, ballerinas are able to make a distinctive impression, telling us something about how they perceive Raymonda as a character.

We have given you examples of Bolshoi ballerinas above because the complete Raymonda hasn’t been performed by a British company since 1964, whereas this Moscow Company has a strong tradition of performing the complete ballet. Happily, however, there is footage available of two exceptionally influential ballerinas in the realm of British ballet dancing the Act III variation. They are Sylvie Guillem, and Tamara Rojo. As in the case of Alexandrova and Smirnova, their individual shaping of the choreography reveals different facets of Raymonda’s persona: while Guillem accentuates Raymonda’s sway over the audience through her expansive use of the kinesphere and impactive phrasing, Rojo creates a sense of mystery and suspense with mesmerising gestures that trace their way through the space more gradually, and keep us guessing when she may deign to bring her movement to a close.

If any of you are still in doubt about the potential power of Raymonda’s choreography, just take a look at the coda to the Grand Pas. Here the ballerina demonstrates her authority through a succession of commanding retirés passés en arrière: tempi, rate of acceleration, rhythm and dynamics vary enormously from dancer to dancer, as do the accompanying port de bras, despite the apparent simplicity of the vocabulary. The radiant energy with which two of our favourite Raymondas, Altynai Asylumuratova and Maria Alexandrova, take charge of the choreography and fashion it to their desire brings to mind the determination, resilience, vision and zest for life that we associate with some of the most celebrated queens of the 12th and 13th centuries, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204), Berenguela of Castile (1179-1246) and Tamar of Georgia (1166-1213). For us, therefore, despite the ballet’s perplexing scenario, Petipa, Glazunov and the ballerinas bringing flesh to the “skeleton” they created (Banes 9) transform Raymonda herself into a person of prowess in body, mind and spirit.

In 2002 Tomalonis asked the question “Can this story be saved?”. Well, it looks like saved is exactly what it’s going to be.

Prior to the planned premiere in the autumn of last year, Tamara Rojo, who is mounting the new production, had been conducting research in preparation for her production of Raymonda for no less than four years. She had researched not only the ballet itself, but also, in a flight of creative imagination, the life of Florence Nightingale, who has inspired the reimagining of the titular protagonist.

So what do the fictional 13th century French countess, and the 19th century English middle-class founder of modern nursing have in common? Well, perhaps the point is that in order to “save” the narrative, Raymonda needs to be seen through a radical new lens. There is no doubt that Florence Nightingale was a woman of high intelligence, extraordinary vision and resilience, willing to take risks in her fierce determination to pursue her vocation; “safe option” was undoubtedly not a phrase in her vocabulary.

Rojo has reconceived Raymonda as a young woman who makes the decision to leave her home in England to become a nurse at the frontline of the Crimean war. Not only is the background of war maintained in this way, but the context facilitates the creation of two contrasting love interests: the English soldier John and the Ottoman Commander Abdur. This Raymonda is described as a “heroine in command of her own destiny” (“Tamara Rojo’s Raymonda”). It is her decision to leave home, to become a nurse, and to become a nurse in a danger zone: we assume that she will also make her own decisions when it comes to affairs of the heart …

We began this post with a conundrum: a ballet with a sumptuous score, glorious choreography, and a highly problematic plot. Rojo recognises this conundrum only too well:

Raymonda is a beautiful ballet – extraordinary music, exquisite and intricate choreography – with a female lead who I felt deserved more of a voice, more agency in her own story (“Tamara Rojo’s New”).

We are looking forward to Raymonda finally joining the canon of beloved 19th century classics in this country, with a new identity through which the Raymonda of the narrative and the Raymonda of the choreography are reconciled.

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

“Alexander Glazunov ‘Raymonda’ (Ballet in three acts)”. UVisitRussia, https://www.uvisitrussia.com/theaters/theater/mariinsky/mar_raymonda/2015-05-09/19:01/.

Alexandrova, Maria. “Maria Alexandrova – Raymonda”. YouTube, uploaded by BalletForever, 23 Jan. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1adEbQrdGE&t=691s.

Anderson, Zoë. The Ballet Lover’s Companion. Yale UP, 2015.

Asylmuratova, Altynai. “Раймонда фрагменты – Алтынай Асылмуратова”. YouTube, uploaded by Stanislav Belyaevsky & Anastasia Dunets, 19 July 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AweKN-R9-Dc.

Banes, Sally. Dancing Women: female bodies on stage. Routledge, 1998.

Dix, Laurel. “Raymonda an Exercise in Elegance”. SeattleDances, 9 Aug. 2012, http://seattledances.com/2012/08/raymonda-an-exercise-in-elegance/.

Guillem, Sylvie. “Sylvie Guillem Raymonda”. YouTube, uploaded by braga144 b, 17 Mar. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=PHZTTYmuCNk.

Khadarina, Oksana. “Elegance & Exuberance”. Fjord Review, 2 June 2020, fjordreview.com/mariinsky-ballet-raymonda/.

—. “Mariinsky Ballet – Raymonda – Washington”. DanceTabs, 28 Feb. 2016, dancetabs.com/2016/02/mariinsky-ballet-raymonda-washington/.

Makarova, Olga. “Alexander Glazunov ‘Raymonda’ (Ballet in three acts)”. Ballet and Opera, 2018, https://www.balletandopera.com/classical_ballet/mar_raymonda/info/.

Pashkova, Lydia Alexandrovna. “Libretto of Raymonda”. A Century of Russian Ballet, edited by Roland John Wiley, Dance Books, 2007, pp. 393-401.

Raymonda. Choreographed by Marius Petipa, reconstructed by Sergei Vikharev, performance by Olesya Novikova, and La Scala Ballet. 1999, Arthaus Musik, 2001.

“Raymonda Origin and Meaning”. NameBerry, 2021, https://nameberry.com/babyname/Raymonda.

Rojo, Tamara. “Tamara Rojo and Akram Khan on this reimagined Giselle”. English National Ballet, 2017, www.ballet.org.uk/production/akram-khan-giselle/.

—. “Raymonda:Tamara Rojo”. YouTube, uploaded by Kabaiivansko2, 8 July 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQxlfxqOtIU.

“Tamara Rojo’s new Raymonda and ENB in 2020-2021”. Seen and Heard International, 30 Jan. 2020, seenandheard-international.com/2020/01/new-tamara-rojos-new-raymonda-and-enb-in-2020-2021/.

“Tamara Rojo’s Raymonda shortlisted for the FEDORA VAN CLEEF & ARPELS Prize for Ballet 2021”. English National Ballet, 2 Feb. 2021, www.ballet.org.uk/blog-detail/tamara-rojos-raymonda-fedora-prize-2021/.

Smirnova, Olga. “Olga Smirnova – Raymonda Act I”. YouTube, uploaded by BalletForever, 9 Jan. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAPL7bO1J1E&t=260s.

Sulcas, Roslyn. “Saracens, Hungarians and Knights who just happen to be in Provence”. New York Times, 2 Dec. 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/arts/dance/03raym.html.

Tomalonis, Alexandra. “Can this story be saved?”. Ballet Alert!, 6 Mar. 2002, balletalert.invisionzone.com/topic/1903-can-this-story-be-saved/.

—. “The Mysteries of ‘Raymonda’”. Danceviewtimes, 9 Mar. 2016, www.danceviewtimes.com/2016/03/the-mysteries-of-raymonda.html.

Ward, Janet. “Olga Smirnova Debuts in Raymonda at the Bolshoi Ballet”. Bachtrack, 15 Feb. 2016, bachtrack.com/review-raymonda-smirnova-bolshoi-ballet-new-stage-moscow-february-2016.