The 19th Century Canon Now

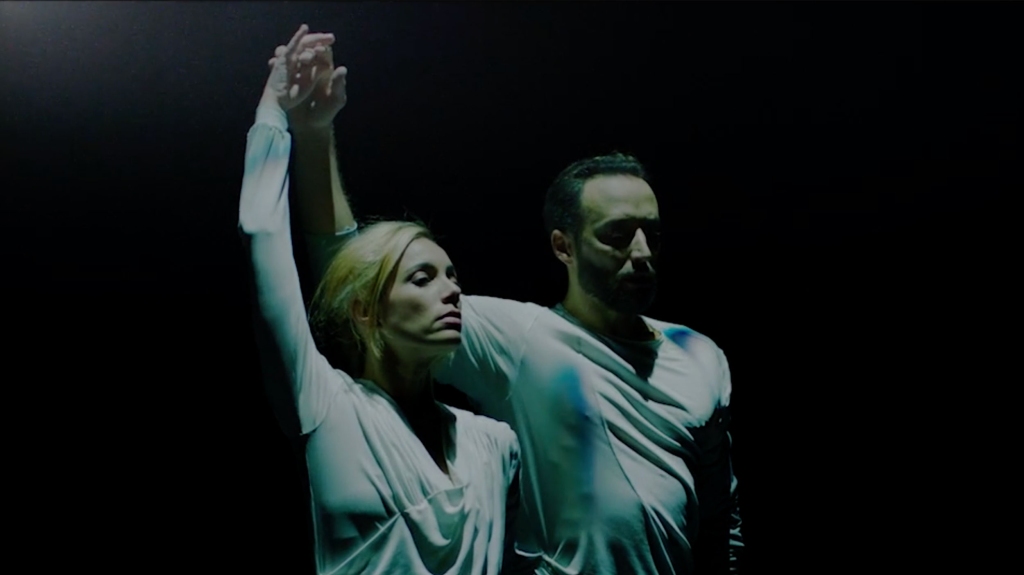

Last summer Birmingham Royal Ballet (BRB) brought their new production of Marius Petipa’s 1869 Don Quixote to London, after it had premiered four months earlier at the Birmingham Hippodrome. With the exception of The Nutcracker, which is pretty much obligatory fare for any major ballet company (as discussed in our very first British Ballet Now & Then post, this was the first work from the 19th century ballet canon to have been performed by BRB since Carlos Acosta took over as Artistic Director in January 2020. The premiere had originally been planned for the start of Acosta’s inaugural season, but like so many productions had to be postponed due to the Covid pandemic.

The choice of Don Quixote in favour of any other work from the 19th century canon was hardly surprising: Acosta himself has been long associated with the role of Basilio. At the age of 17 he won the Prix de Lausanne after dancing Basilio’s Act III variation; he performed the role with the Royal Ballet (RB) in Rudolf Nureyev’s staging mounted by Ross Stretton and then created his own production of the ballet for the Company, now adapted for his own Company.

Like the other 19th century classics, Don Quixote provides technical challenges for dancers of different ranking, and opportunities for a large cast of performers to engage in different styles: classical, character and mime. Other works in the British ballet repertoire that offer similar opportunities are La Sylphide (Bournonville, 1836), Giselle (Coralli/Perrot, 1841), Coppélia (Saint-Léon, 1870; Petipa, 1884) La Bayadère (Petipa, 1877), The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890), Swan Lake (Petipa/Ivanov, 1895) Raymonda (Petipa, 1898) and Le Corsaire (Petipa, 1899).

Apart from the fact that these works were all created during the 1800s, when ballet as an art form became more recognisably what we understand as ballet today, with its focus on the female dancer, themes inspired by Romanticism, and development of pointe work and ballets blancs, they are all connected by the fact that they were originally choreographed in France or Russia and “travelled” to this country via various routes (as we will discuss further in the Then section of this post). Although we are sure that you are all familiar with Don Quixote, La Bayadère, Raymonda and Le Corsaire, these works took a number of decades to become established within the British repertoire, being produced in the UK at different times by different companies from 1962 to 2022, and not always in their entirety.

If you follow this blog, you will already know the history of Raymonda in the UK prior to English National Ballet’s evening-length production, which premiered in January last year. Important details for this particular post is the fact that it was Nureyev, just three years after his defection from the Soviet Union, who first staged Raymonda in this country, initially in a complete production for the Royal Ballet (1964), and then as a one-act ballet based on the final act of the work, in 1966. In this form Raymonda can stand on its own as a divertissement within a mixed bill, and between 1993 and 2014 English National Ballet also performed a single-act Raymonda, firstly in a production by Frederick Franklin (the British-American dancer, teacher, choreographer and director), and then, in 1993 in Nureyev’s staging, as part of the Nureyev Celebration, marking 75 years since Nureyev’s birth and 20 years since his death.

Similarly, it was Nureyev who first staged La Bayadère in the UK—not in its entirety, but in that superb example of high classicism, the “Kingdom of the Shades”—and who introduced the Le Corsaire grand pas de deux to the British repertory. In 1985 the “Kingdom of the Shades” entered the repertory of English National Ballet in a production by Natalia Makarova, and in 2013 the same company became the only British ballet company to perform the complete Corsaire.

The three most celebrated ballet defectors from the Soviet Union all had a tremendous impact on dancing in the West, but like Nureyev, Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov also had a substantial influence on the expansion of the 19th century repertoire, by staging major full-length productions for American Ballet Theatre: La Bayadère (Makarova, 1980) and Don Quixote (Baryshnikov, 1978). Relevant for the development of British ballet is the fact that both of these productions were also mounted on the Royal Ballet. While La Bayadère was the first complete version of the work to be performed in Britain (and remains the only full-length production in the UK), Don Quixote has had a far more varied history in this country, including stagings by Ballet Rambert (1962) and by London Festival (now English National) Ballet (1970), both mounted by Polish ballet master Witold Borkowski, in addition to the two more recent RB productions. It seems that it is only since the RB’s staging of Baryshnikov’s version in 1993 that the work has become more firmly established within the British ballet repertoire.

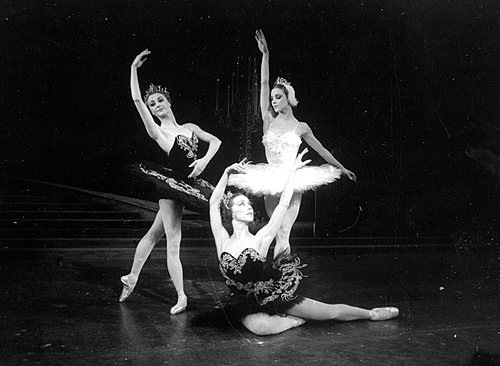

Although these star dancers from the Soviet Union also mounted new productions of 19th century works already established within the British ballet repertoire (including Nureyev’s Nutcracker for the Royal Ballet in 1968, and Makarova’s 1988 production of Swan Lake for London Festival Ballet), it is noticeable that they focused their efforts primarily on the 19th century works that they knew from their experiences at the Vaganova Academy and Mariinsky Ballet but were absent from North American and Western European companies. And the newer 19th century additions to the British ballet repertoire have indubitably enriched our understanding of ballet as an art form, given dancers new challenges and offered audiences both entertainment and food for thought. Don Quixote belongs to a very small number of comedic ballets, and provides a great variety of character and demi-character roles. Le Corsaire is teeming with opportunities for virtuoso male dancers. And can any scene in the ballet repertoire surpass the transcendence of the “Kingdom of the Shades”?

Yet even ballet, with its highly stylised technique, and its penchant for magic and fantasy and reputation for escapism, is not immune from the changing attitudes of our Zeitgest. Although ENB’s production of Le Corsaire is little over a decade old, the last time it was performed (at the start of 2020), it came with a caveat from the Artistic Director, Tamara Rojo:

When English National Ballet commissioned its new production of Le Corsaire, we worked to challenge some of the traditions of this work, and therefore made adaptations to tone [down] the characters. We know that still some elements, such as the attitude towards women and other cultures, now seem unacceptable to our values. However, we present this traditional work with the strength of the assumption that the audience has the knowledge and the critical frame of judgement to view them in the context in which they were created.

As explored in our Raymonda post, in her own 2022 production of Raymonda, Rojo was at pains to address conflicts between current attitudes and those prevalent in Petipa’s original production, by offering a heroine with greater agency over her own life, and a reconceptualisation of Abderakhman the Muslim Saracen to address the traditional othering of this character.

The Royal Ballet last staged La Bayadère in 2018. For the most part, as is usual for works that are already established in the repertoire, reviews highlighted the performances of the principals, and as is usual for works which feature major ballets blancs, commented on the unison of the corps de ballet (Desvignes; Hugill; Jennings; Parry). However, both Robert Hugill and Luke Jennings raised concerns regarding Bayadère‘s promotion of orientalist attitudes manifest in “its inanely capering fakirs, lustful priests and blithe appropriation of Hindu, Islamic and Buddhist religious and cultural motifs” (Jennings).

In recent years BRB, ENB, RB, and Scottish Ballet have all made revisions to the choreography, costumes and/or make-up of the Arabian and Chinese Dances from the Nutcracker productions in order to start confronting such offensive stereotypes. But how does a company approach revising a whole full-evening work?

In the United States, Arts Educator and Co-founder of Final Bow for Yellow Face Phil Chan is producing his own versions of Le Corsaire and La Bayadère to make them more suitable and relevant for American 21st century audiences by addressing what he perceives to be their inherent racism and misogyny. In his plans, Le Corsaire takes place at a beauty pageant complete with “scheming showgirls, gunslinging beauty queens” (Chan), while La Bayadère will feature Hollywood cow girls and references to Busby Berkeley’ oeuvre, as well as a plot line similar to Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly, 1952). These ideas may avoid racial stereotyping, but on paper at least they seem to raise other problematic issues. Neither do we understand how the tragic nature of La Bayadère will translate into this new context. Perhaps the productions themselves will transcend their description on paper …

The 19th Century Canon Then

In the 1920s and early 1930s, when Marie Rambert and Ninette de Valois were taking their first steps to establish ballet as a British art form, there was no canon of 19th century “classics” as we know it today.

So what exactly was the tradition of ballet in 19th century Britain?

Well, in the 1840s, during the flourishing era of ballet Romanticism, Her Majesty’s Theatre Haymarket became a centre for the art form, with important works being created there by the pre-eminent French choreographers of the day Jules Perrot (co-creator of Giselle in 1841, with Jean Coralli) and Arthur Saint-Léon (choreographer of Coppélia, 1870). These included Ondine, La Esmeralda and Pas de quatre by Perrot, and La Vivandière by Saint-Léon. However, the situation changed radically in the later decades of the century, when music halls and variety theatres, such as the Empire and the Alhambra on Leicester Square, became regular venues for ballet performances, a situation that continued into the 20th century. Despite the frequency of performances and popularity of ballet in these theatres, the works created specifically for the music halls were short lived, and even the names of the choreographers, such as Carlo Coppi and Katti Lanner, are not generally well known to today’s ballet-going public. Further, these connections to popular theatre meant that the status of ballet as a serious art form was on thin ice, even though versions of Giselle and Coppélia, now generally considered as works of the highest calibre, were staged at the Empire in the 1880s. And when in 1921 Serge Diaghilev mounted his sumptuous production of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty, based on Marius Petipa’s 1890 choreography but titled The Sleeping Princess, it was also produced in a music hall setting: at the Alhambra.

When de Valois set up the Vic-Wells Ballet (later to become the UK’s flagship company the Royal Ballet) in 1931, she had a clear vision of the kind of repertoire she considered necessary for a national British company. It consisted of four categories:

- Traditional-classical and romantic works

- Modern works of future classic importance

- Current works of more topical interest

- Works encouraging a strictly national identity in their creation generally

(Bland 57)

With both Ashton and herself at the helm creating new choreographies, it is clear how her last three aims might be fulfilled. But of course, what interests us in this post is the way de Valois obtained the “Traditional-classical and romantic works”.

What we find fascinating is that political events came to de Valois’ aid: like many other figures from the Russian ballet world, the Mariinsky régisseur Nikolai Sergeyev had fled his home after the 1917 Revolution. With him he took scores of 19th century works in a dance notation system devised by Vladimir Stepanov. These included The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, as well as Giselle and Coppélia; ballets of which de Valois had some, but limited, knowledge (Walker 129). The distinct advantage of mounting the works from the notation scores was of course that it must have given a sense of gravitas to the productions through an authenticity that most music hall productions were unlikely to match, even if that was indeed an aim. Before Sergeyev started to work for de Valois, he had already staged two works in London: Diaghilev’s The Sleeping Princess, and The Camargo Society’s Giselle. However, the work of staging these ballets for de Valois’ fledgling company created a cornerstone of the British ballet repertoire. Further, this process was solidified by Mona Inglesby, founder of International Ballet in 1941, another highly significant figure who promoted 19th century works in Britain, and for whom Sergeyev worked from 1946 until his death in 1951. Crucially, the company toured these works the length and breadth of the British Isles: from the suburbs of London through the Midlands to Liverpool and Manchester, up to Newcastle, Glasgow and Edinburgh, and over to Belfast and Dublin. In fact, although the Company folded in 1953, International Ballet was of such significance in its day that it was chosen to appear at the opening of the Royal Festival Hall in 1951.

De Valois’ and Inglesby’s selection of works seems highly interesting to us, because the ballets they produced constituted only approximately one quarter of the works that could have been staged. La Bayadère, Le Corsaire and Raymonda could have entered the British ballet repertoire decades sooner; we might have enjoyed The Pharaoh’s Daughter (Petipa, 1862) and La Esmeralda (Petipa after Perrot, 1886) or the Petipa and Ivanov version of La Fille mal gardée (1885). Both Inglesby and Pavlova before her had made plans to produce La Bayadère, but had reached the conclusion that it was “too old fashioned” (Inglesby 97; Pritchard “Bits” 1121). While Pavlova did mount a version of Don Quixote, according to historian and expert in British ballet history, Jane Pritchard, this also struck audiences as rather dated after Leonid Massine’s Le Tricorne (1919) (Anna Pavlova 112). La Esmeralda also proved enticing to Inglesby, but was rejected as a project by the Royal Opera House (Inglesby 106-107). On other hand, Giselle, Coppélia, The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake all had two distinct advantages: they had already been introduced to the British public, and they all had superb scores (Tchaikovsky was known to have admired the compositions of both Adolf Adam and Leo Delibes) (Pullinger).

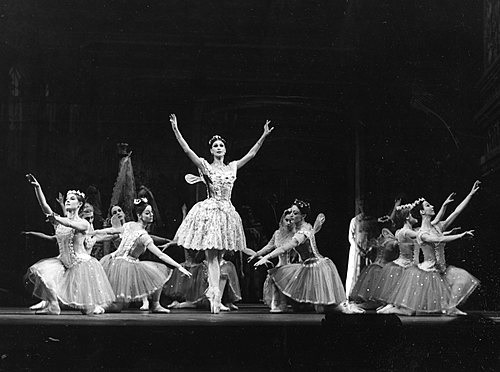

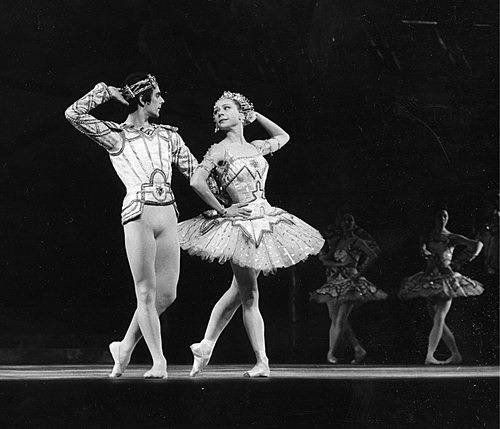

In addition to music hall performances of Coppélia at the Empire Leicester Square from the 1880s into the early 1900s, we were also intrigued to discover that in 1890, the same year that Petipa had choreographed the ballet for the Mariinsky Theatre with Carlotta Brianza as Aurora, one of the other Italian ballerinas who starred with the Russian Imperial Ballet, Pierinna Legnani, had danced the same role in a full production at the Alhambra, but to the choreography of Leon Espinoza with music by Georges Jacobi. Further, in the years immediately leading up to the first London season of the Ballets Russes in 1911, the West End evidently became a veritable hive of ballet activity, with appearances from Lydia Kyasht, Tamara Karsavina, Olga Preobrazhenska, Alexandra Baldina, Ekaterina Geltzer, and of course Anna Pavlova. Included in these performances were shortened versions of works that were to become “the classics”: in 1910 Preobrazhenska staged Swan Lake at the Hippodrome, while Karsavina mounted a truncated production of Giselle at the Coliseum. The following year saw the complete Giselle, The Sleeping Beauty Grand pas de deux and a two-act condensed Swan Lake at the Royal Opera House performed by the Ballets Russes.

And what of the ubiquitous Nutcracker? Well, if you have been following British Ballet Now & Then since the start, you will know that the notion of The Nutcracker as a quasi-obligatory Christmas treat is a phenomenon of the later 20th century. In fact this ballet was not well known in this country before de Valois’ Vic-Wells Ballet staged it in 1934. However, the Nutcracker Suite, which was in fact presented in concert halls before the ballet premiered at the Mariinsky Theatre, was performed in London as early as 1896.

Ballets Russes audiences would also have known some excerpts, because Diaghilev himself was a great admirer of the score and interpolated some of the numbers into his productions of The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake (Newman 20-21).

But you may be asking yourself how La Sylphide became integral to the 19th century canon. The original work by Filippo Taglioni, created for his daughter Marie Taglioni, the most celebrated of Romantic ballerinas, was hugely popular in its day and was performed at Covent Garden only a few months after the March premiere in Paris, 1832. Marie Taglioni also performed it in Russia, where it continued to be included in the repertoire, and was revived by Petipa in 1892. However, it does not seem to have been amongst the works that were recorded in the Stepanov notation, and sometime during the first half of the last century Filippo Taglioni’s choreography was lost, although the Romantic ballet expert Pierre Lacotte did produce a reconstruction of it for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1972. As you probably are aware, the choreography that has been passed down through the generations is the version by August Bournonville, who saw the original production in Paris, but then created his own in 1836. According to Pritchard (who also happens to be one of our favourite dance historians), Marie Rambert, who established the first ballet company in the UK, loved Romantic ballet (“Marie Rambert” 1177). She had become familiar with Giselle during her time with the Ballets Russes, and in 1946 Giselle became the first long work to enter the repertoire of Ballet Rambert (now Rambert). This production was staged with the help of historian Cyril Beaumont, author of The Ballet Called Giselle, first published in 1944, and still available to purchase today. Beaumont devotes a substantial section of his book to La Sylphide, exploring its influence on Giselle in terms of themes, style, technique and structure. The work he discusses is the original Taglioni La Sylphide, which was of course not available for Rambert to stage. Instead, the Bournonville version was staged in 1960, by Bournonville expert Elsa Marianne von Rosen. In contrast to the full-length Giselle and La Sylphide, only extracts from The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake were performed by Rambert. However, Rambert seems to have produced an appetite for Bournonville’s ballet in Britain: Danish ballet master Hans Brenaa was invited to stage a production for Scottish Ballet in 1973; in 1979 the Danish dancer Peter Schaufuss (later to become Artistic Director) mounted his production for English National Ballet; and eventually the Royal Ballet acquired the work in Johan Kobborg’s 2005 staging. Perhaps one factor that contributed to the growing familiarity with La Sylphide of the British ballet audience was the BBC broadcast of the Act II Pas de deux in 1960 with von Rosen herself, followed by a broadcast of the complete work with Ballet Rambert less than a year later. Another factor was undoubtedly Rudolf Nureyev’s performances with Scottish Ballet at the London Coliseum in 1976, in which he danced James at every performance over the course of two weeks.

Concluding thoughts

A brief glance through Instagram leaves us in no doubt about the popularity of the 19th century canon across the globe. And the importance of the works to the British ballet repertoire cannot be denied: in the 2022-2023 season, in addition to the The Nutcracker, Birmingham Royal Ballet have performed Swan Lake, English National Ballet both Raymonda and Swan Lake, and the Royal Ballet The Sleeping Beauty.

We perhaps think of the classics as being exempt from politics, but this is a fallacy: neither their content nor their arrival to these shores can be said to be divorced from politics. The word “timeless” is also often associated with the term “classics”, but of course the style of performance varies over space and time and our perception of and relationship with the works changes with the Zeitgeist.

Ballet has traditionally been perceived as an ephemeral art form, being handed down by dancers from generation to generation, with limited means for recording the choreography. But today, with the regular use of Benesh Movement Notation and video to record works in their different productions, perhaps we can feel more secure about the preservation of the 19th century repertoire.

How would you like to see these works preserved? Would you like to see them performed in a style more compatible with the original style, with original choreography restored, as Alexei Ratmansky has done with his productions of The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake? Or would you prefer a more experimental approach, in response to a more contemporary world view, such as that proposed by Phil Chan? We would love to hear your thoughts!

© British Ballet Now & Then

We would like to thank our dear friend and colleague Paul Doyle for his help with this post.

Next time on British Ballet Now and Then … Ballet has a reputation for being very gender specific. However, there is a tradition of subverting gender norms in certain circumstances. The Royal Ballet’s recent run of Cinderella has seen both female and male identifying dancers perform the Step-Sisters, while the last time English National Ballet staged The Sleeping Beauty, the cast included a gender-fluid dancer, as well as both male and female performers in the role of Carabosse. So this will be the focus of our next Now and Then post …

References

Beaumont, Cyril W. The Ballet Called Giselle. Dance Books, 2011.

Bland, Alexander. The Royal Ballet: the first fifty years. Threshold Books, 1981.

Chan, Phil. “On Yellowface and a way forward for Diverse Audiences”. One Dance UK, 2020, https://www.onedanceuk.org/resource/on-yellowface-and-a-way-forward-for-diverse-audiences/.

Desvignes, Alexandra. “Marianela Nuñez shines in a star-studded, polished Bayadère at The Royal Ballet”. Bachtrack, 3 Nov. 2018, https://bachtrack.com/review-bayadere-royal-ballet-nunez-muntagirov-osipova-opera-house-london-november-2018.

Hugill, Robert. “Iconic but flawed: La Bayadère the Royal Ballet”. Planet Hugill, 12 Nov. 2018, https://www.planethugill.com/2018/11/iconic-but-flawed-la-bayadere-royal.html.

Inglesby, Mona, with Kay Hunter. Ballet in the Blitz: the story of a ballet company. Groundnut Publishing, 2008.

Jennings, Luke. “La Bayadère review – moonlit heights from Nuñez and co”. The Guardian, 11 Nov. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/nov/11/la-bayadere-royal-ballet-review-marianela-nunez-natalia-osipova.

Newman, Barbara. The Nutcracker. Aurum Press, 1985.

Parry, Jann. “Royal Ballet – La Bayadère – London”. DanceTabs, 6 Nov. 2018, https://dancetabs.com/2018/11/royal-ballet-la-bayadere-london-2/.

Pritchard, Jane. Anna Pavlova Twentieth Century Ballerina,

—. “Bits of Bayadère in Britain”. Dancing Times, vol. no. , 1989.

—. “Marie Rambert”. International Dictionary of Ballet, edited by Martha Bremser, St. James Press, 1993, pp. 1175-77.

Pullinger, Mark. “A step into the world of Tchaikovsky’s ballets: Swan Lake”. Bachtrack, 23 July 2017, https://bachtrack.com/ballet-focus-tchaikovsky-swan-lake-petipa-july-2017.

Rojo, Tamara. “A Word from Tamara Rojo, Artistic Director”. Le Corsaire programme Jan. 2020, English National Ballet, London.

Walker, Katherine Sorely. Ninette de Valois: idealist without illusions. Dance Books, 1987.