Introductory thoughts

If you are a regular reader of British Ballet Now & Then, you will know that what we offer here is a personal perspective on British ballet based on our own experiences of watching various British ballet companies over the years, and in some cases over a number of decades. Inevitably, therefore, readers will notice lacunae in our discussion of English National Ballet (ENB) now & then (and please feel free to object!), but part of what makes this particular post so personal to us is the selection of directors, dancers, and repertoire that are alive in our memories and consequently form the foundation of our tribute to the Company in its 70th anniversary year.

For our Now section we are focussing on the period from 2012, that is, the period of Tamara Rojo’s directorship, as the steady realisation of her vision for the Company has already had a significant impact on both ENB itself and on ballet as an art form in Britain.

ENB Now

It comes as no surprise to us that as a director Rojo has a very clear vision for her company. After all, as a ballerina she has always expressed exceptional vision, demonstrated in the distinctive way in which she shapes her articulation of choreography and character. This is evident in recordings of her work portraying a gamut of complex characters, from Marius Petipa’s Nikiya (La Bayadère, 1877), Kenneth MacMillan’s Juliet (1965) and Manon (1974) to Ashton’s Isadora (1976) and Akram Khan’s Giselle (2016). Rojo’s distinctiveness, the intensity of her commitment to performance and dramatic cogency in her repertoire, has been commented on by critics including Zoë Anderson, Sarah Crompton, Luke Jennings (“Step into the Past), and Judith Mackrell (“Giselle”). These qualities seem to us to be integral to what dance writer Graham Watts describes as being “possessed of an exceptional independence of spirit and a remarkable enquiry into [her] art”.

As expressed in their 2017-2018 Annual Review, ENB aims to “develop the art form of ballet by commissioning new choreography, design and musical composition as well as cherishing the classical repertoire” (5). So let’s have a look at how ENB’s choice of repertoire reflects these aims …

Rojo’s very first season as Artistic Director opened with Kenneth MacMillan’s production of The Sleeping Beauty, which had been in repertoire since 2005. The Sleeping Beauty is widely perceived as the pinnacle of classical ballet (Dodge; “The Sleeping Beauty Live”; Speer), and indeed, when we witnessed its revival in 2018 with Jurgita Dronina in the title role, it did indeed look “cherished”, as also attested by the critics (Anderson; Gilbert; Jennings “English National Ballet”). Something that is very noticeable about the 19thcentury repertoire when performed by this company is the attention paid to stylistic detail, with the result that each work makes a quite different visual impact, as we have written about previously. In our view this makes for extremely satisfying watching: not only is there a visible distinction between Romantic and classical styles, but even within those eras, there is clear differentiation between the specific articulation of the choreographies. For example, dance writer Judith Mackrell highlights some of the key features of Bournonville’s style in Isaac Hernández’ “beautifully filleted beats and bounding jetés” as James in La Sylphide, and in the way in which Daniel Kraus as Gurn “joyously embod[ies] the mobile twists and turns of Bournonville’s épaulement” (“Song of the Earth). In contrast, Giselle is distinguished by the careful schooling of the corps de ballet in the 19th century French style “as is apparent in their softly rounded arms and restrained line” (Jennings “Giselle Review”), while performances of the Russian Imperial Sleeping Beauty “evince …an absolute commitment to classical style and stage manners …You can see the concentration on the placement of arms and shoulders, on the expressiveness of wrists and hands, on the line of the neck and precise direction of gaze” (Jennings “English National Ballet”).

Like The Sleeping Beauty, Le Corsaire was choreographed by Marius Petipa for the Russian Imperial court. But unlike The Sleeping Beauty, which holds a special place in British ballet history, the complete Le Corsaire is a recent addition to the British repertoire, having been staged for the first time in this country by English National Ballet in 2013. And unlike The Sleeping Beauty, Le Corsaire requires the kind of extravagant bravura in both classical and character dancing that is not generally associated with English style ballet. Yet the Company has risen to this challenge with great spirit and self-assurance. This was noted in reviews (Byrne; Gilbert; Winship), as well as in our own “In Conversation” post. Emma Byrne’s headline description “A swaggering, bravura spectacle” already conveys a strong sense of the dancers’ bold commitment to the style, as does Jenny Gilbert’s rendition of Jeffrey Cirio’s Ali, who “wins the biggest cheers of the night for his aerial fireworks, explosive energy following through to the tips of his fingers”. We found it fascinating to discover as part of our research that ENB President Beryl Grey had discussed her thoughts on the Russian tradition of performing as part of her “Desert Island Discs”. These thoughts were based on her first-hand experiences of dancing with the Bolshoi Ballet (more of Beryl Grey in the “Then” section of this post):

The dancers, they lived every single small role up to the biggest role … And I think you have in the Russian dancers this tremendous capacity to make believe. And they’re never embarrassed – the ones I worked with anyway were never embarrassed – whereas, in England … in my days one sort of half acted … until the performance … but in Russia every single rehearsal was full out, like a performance, and they actually get into the roles and live them truly. (31:12-32:13)

Let’s turn to Jenny Gilbert once again to reaffirm the achievement of ENB in this ballet, and make a connection between their physical commitment to the style and Grey’s description above:

The plot [of Le Corsaire] is, frankly, ridiculous … It’s the sort of hokum it normally takes a Russian company to bring off, but English National Ballet meets the challenge with a swagger in its revival of Anna-Marie Holmes’s 2013 production.

So while the collection of works itself is of course significant, the understanding of style conveyed through the performance of those works demonstrates a commitment to “cherishing” the choreography rather than simply maintaining the works within the repertoire. Jennings attributes this commitment to Rojo and her teaching staff (“English National Ballet”), as do we ourselves, having had the opportunity to watch her in rehearsal as well as in performance. Further, one of the benefits of the Covid-19 lockdown seems to have been an increased number of opportunities to hear discussions with Rojo on various aspects of her professional life as both director and dancer. From one of these discussions we are given an insight into Rojo’s hunger for knowledge and understanding, and her creative thinking in the face of adversity:

One thing that I thought was a negative when I was young has turned out to be a great positive … I did not come from any consolidated, respected ballet school: I did not come from Paris Opera, from the Bolshoi, from the Mariinsky, from the Royal Ballet School. And I always felt that I did not belong to one particular school and that that was a minus. But in a way that actually was a huge plus, because first of all it gave me this imposter syndrome that meant that I kind of researched like a crazy person every aspect of each style, feeling that I had to do extra work because I wasn’t part of it. (“Tom and Ty Talk 23:12-23:58”)

As for ENB’s aim to develop the art form of ballet, there is ample evidence of this. Amongst the names of choreographers who have created new work for the Company are William Forsythe, Akram Khan, Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa, Russell Maliphant and Yabin Wang, all of whom have demonstrated challenges to traditional ballet in their commissioned works for ENB. This is completely in line with Rojo’s vision for her Company, her belief in ballet as an art form and her dedication to its continuing relevance.

There is no doubt in our minds that the jewel in the crown of ENB’s new repertoire since 2012 is Akram Khan’s Giselle. In an interview with Keke Chele of JoBurg Ballet, Rojo explained her decision to commission Akram Khan to reimagine the canonical Giselle:

I’ve always been fascinated by ballet history, and in my opinion it has been when our artform has been “polluted” (like the traditionalists would say) by other types of dance, whether that was folklore or musics that were not considered proper for ballet, or themes, you know like when Kenneth MacMillan started to introduce Manon, Mayerling, or you know, by different, like cross-fertilisation, is when I think cultures become better and arts become better, and that was my motivation to bring Akram. This is an exceptional artist that I’ve admired for many years, that I’ve seen so many of his shows that had such capacity for story-telling and such strong technique of his own, that was kathak and contemporary, that I knew that he will understand an art form that is equally demanding in technique – the classical technique of ballet – but also that in itself it is a language to tell stories. (“JoBurg Ballet Off Stage” 18:00-19:04 )

What we find extraordinary about Rojo is the way in which her insight into ballet history has driven her decisions as Artistic Director. In her intrepid interrogation of ballet and its potential, she seems to have revived the spirit of Serge Diaghilev, the redoubtable impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, whose leadership and exceptional vision engendered such radical but enduring works as Bronislava Nijinka’s Les Noces (1923) and George Balanchine’s Apollo (1927).

ENB Then

We first encountered the Company in the 1970s. Some of the ballets we saw in the late 1970s and early 1980s have made an enduring impression on us. We can still remember the curtain rising on the white opening tableau of Les Sylphides (Fokine, 1909) and the hushed atmosphere as the dancers seemed to float downstage. The great Danish mime artist Niels Bjørn Larsen was unforgettable in his charismatic rendition of Madge in La Sylphide (Bournonville, 1836), as was the verve of the corps de ballet in the reel, and the poignancy of Eva Evdokimova’s Sylphide as her sight fails before her death. And what a thrill was Etudes (Lander, 1948) with its seemingly inexorable build-up to the final climax and its sense of competition between the male dancers, particularly when performed by such brilliant virtuosi as Peter Schaufuss, Patrice Bart and Patrick Armand.

But in addition to the imprint these works made on our memories, within this tiny selection of repertoire we can see two distinct trends in the repertoire of London Festival Ballet: the highlighting of the Romantic heritage, and the connection with Danish ballet tradition – trends that Jane Pritchard, Archive Consultant to ENB, has drawn attention to. This is also borne out by lists of repertoire in programmes from the 1950s and early 1960s. These included Anton Dolin’s production of Giselle (Coralli/Perrot, 1841) and his reconstruction of Pas de Quatre (Perrot, 1844); the final act of Bournonville’s Napoli (1846) and the pas de deux from his 1858 Flower Festival in Genzano; and from 1909 and 1910 Fokine’s evocations of the Romantic era – Les Sylphides and Le Spectre de la rose.

As we wrote in our first Giselle post, Alicia Markova, who established the Company in 1950 with Anton Dolin, also performed the eponymous heroine in the first British production of the ballet in 1934, after which she became associated with the ballet through the course of her career. Dolin’s production of the ballet was one of the first complete 19th century works to be mounted by Festival Ballet, and according to Pritchard, Markova’s initial involvement in the Company was dependent on having a new production of Giselle created specifically for her, thereby placing this work “at the heart of” ENB. Mary Skeaping’s 1971 staging, commissioned by Beryl Grey, was an extremely important production due the intensive historical research Skeaping had undertaken, which in our opinion gives the ballet more dramatic cogency, as well as a vivid sense of Romantic ballet style. This, our favourite production of Giselle, has been performed by the Company with luminaries of the stature of Rudolf Nureyev and Natalia Makarova, and still receives excellent notices (Crompton; Jays; Watts “English National Ballet’s Exceptional”; Watts “Review”).

The first time Markova performed in Fokine’s Les Sylphides, his tribute to la danse ballonnée, she was only 15 or 16 years old. However, only six years later, and only two months after her debut with the Company in 1932, she mounted the ballet for the Vic-Wells (later Royal Ballet) (Bland 30). Subsequently Markova staged further productions: for American Ballet Theatre (1964), Northern Ballet Theatre (1979), and for our present discussion most importantly her 1976 staging for London Festival Ballet. Although we never saw Markova perform, Rosie has a memory of a photograph of Markova in Les Sylphides from her very first ballet book (which she still possesses), The Girls’ Book of Ballet by A. H. Franks, and was always struck by a quote from Markova about her relationship with the audience: “I do not try to reach out to them; I draw them in to me” (60). In a way Markova continues to draw people to her through recordings of her performances in Giselleand Les Sylphides – recordings originally made in the early 1950s that therefore suggest the importance of these ballets for her career. In fact, the 1951 film of Giselle, with Dolin as Albrecht, is also significant as the oldest surviving recording of English National Ballet.

Therefore, in our minds, through Alicia Markova, Beryl Grey and Mary Skeaping, English National Ballet is undeniably a curator of Romantic style repertoire. As if to emphasise the importance of Romantic themes in the repertoire, Giselle was sometimes performed in a double bill with Le Spectre de la rose, as in the 1976 London Coliseum spring season.

In the early years, the Danish tradition was represented by the two dancers Flemming Flindt and Toni Lander, both of whom had trained at the Royal Danish Ballet School before being accepted into the Copenhagen company. Additionally, in 1955 Lander’s husband Harald staged his work Etudes, which was chosen as the climax to the 70th Anniversary Gala performances, having become a signature ballet for the Company with a total of over 700 performances over the years. Another delicious nugget of information we uncovered was that it was Harald Lander who mounted ENB’s first Coppélia. This was a re-staging of the Danish production first performed in 1896 and “carefully preserved” first by Ballet Master Hans Beck and later by Lander himself (Hall 57).

In the 1970s and 1980s Festival Ballet’s connection with the Romantic and Danish traditions was consolidated and enriched through the dancer and director Peter Schaufuss. Son of two Royal Danish Ballet dancers, and another graduate of the Royal Danish Ballet School, Schaufuss danced with the Company for much of the 1970s and into the early 1980s before becoming Artistic Director. In 1978 he mounted his production of La Sylphide for the first time, with the exquisite and ethereal Eva Evdokimova, renowned for her portrayal of Romantic roles, in the eponymous role, and the supreme Niels Bjørn Larsen as Madge. Ten years later he bestowed another jewel from the Danish tradition on the Company: Bournonville’s three act Napoli (1842).

In our very first British Ballet Now and Then post we explored how The Nutcracker (Ivanov, 1892) became a family Christmas tradition in this country, largely through the work of ENB, who began performing it in its very first season. By the time Grey took over as Artistic Director in 1968, the Company were also performing full-length productions of The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890) and Swan Lake (Petipa/Ivanov, 1895). London Festival Ballet programme notes from 1976 emphasise Grey’s involvement in new productions of these works for the Company.

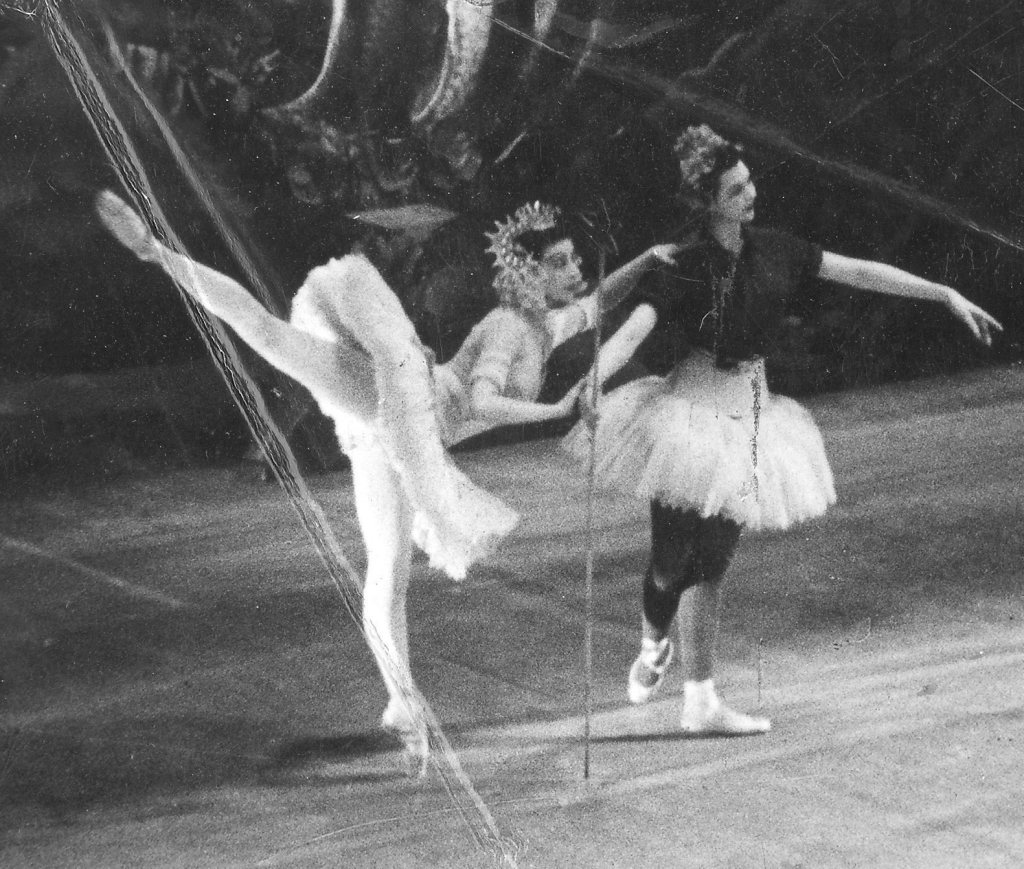

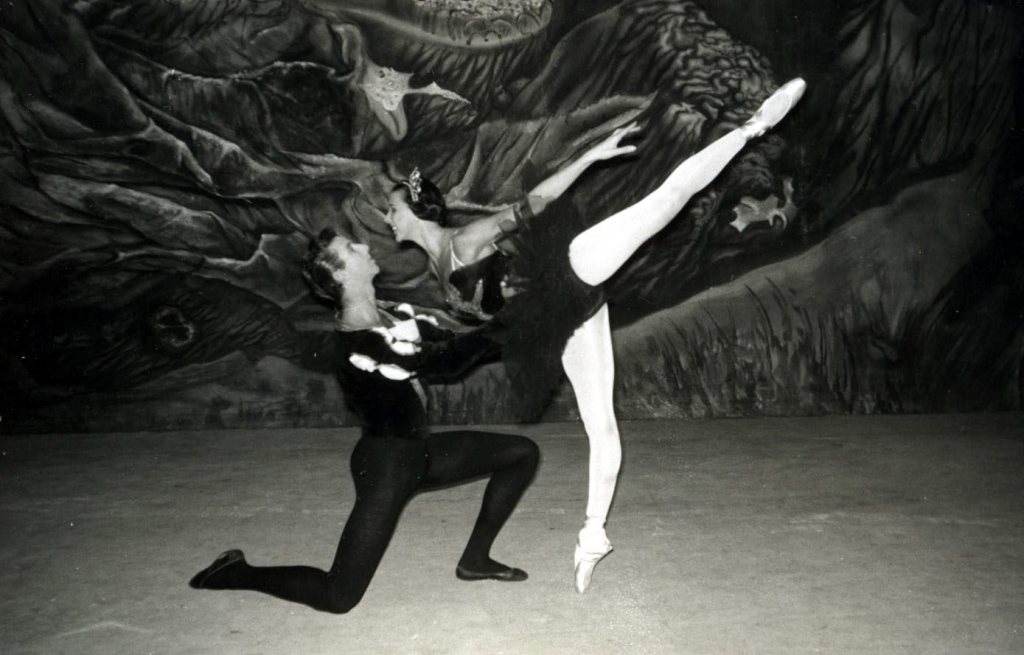

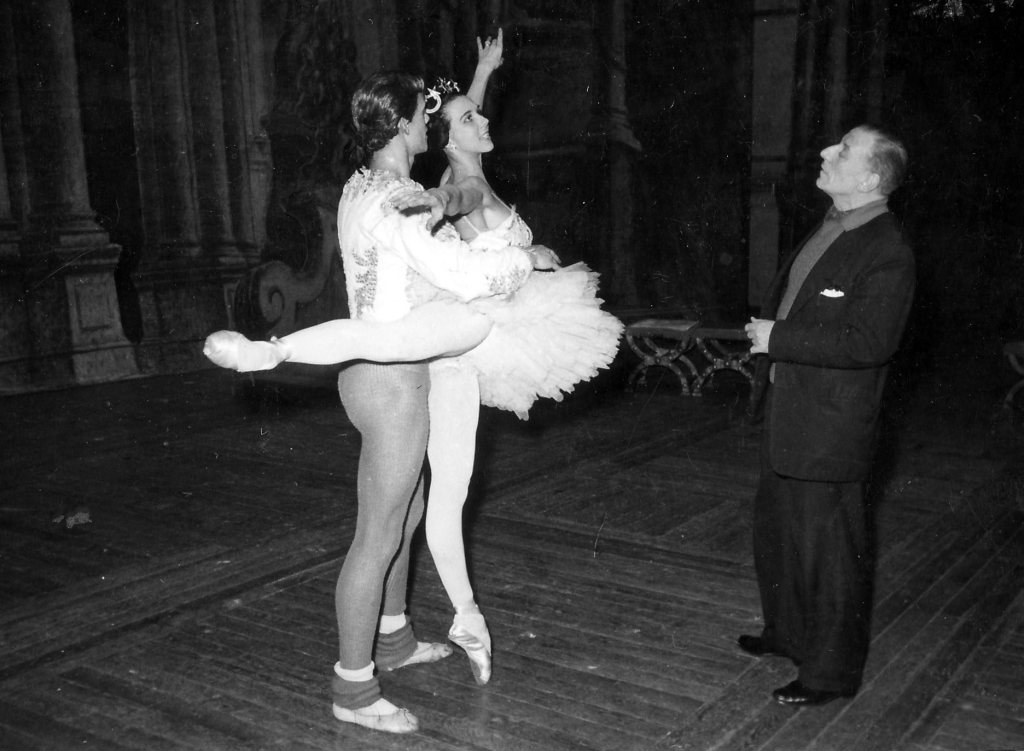

It seems that just as Markova had a special relationship with the ballets Giselle and Les Sylphides, Grey had a special relationship with the ballet Swan Lake, not only due to the extraordinary fact that she performed the dual role of Odette/Odile for the first time on her fifteenth birthday, but also because she was the first Western ballerina to dance in Soviet Russia and in Beijing, and danced this ballet on both occasions.

Grey had been a ballerina with the Royal Ballet and performed the Lilac Fairy to Margot Fonteyn’s Aurora at the famous reopening of the Royal Opera House after World War II. Although Ninette de Valois evidently told Grey she would never dance Aurora as she was “far too tall to manage the attitude balances” of the “Rose Adagio”, Grey was determined to prove her wrong, and in fact she performed the role towards the end of that same season, just after her nineteenth birthday (Grey 51, 54). When Grey performed in China, she also took the opportunity to assist in staging The Sleeping Beauty (195). Although Grey first danced Giselle as a sixteen-year-old, and also performed the role in the Soviet Union, she is perhaps more associated with the character of Myrthe, which she danced to Fonteyn’s Giselle. We loved the discovery that Grey performed the Queen of the Wilis when Markova and Dolin danced in Giselle at the Royal Opera House in 1948, bringing these three key figures together on the stage. In the same year Swan Lake was added to the repertoire at Covent Garden. In her autobiography Grey expresses her excitement at the prospect of dancing her favourite role on the Royal Opera House stage (68).

No doubt we take it for granted that the London Coliseum is a major venue for English National Ballet. However, it was not until Grey’s tenure as Artistic Director that the Company started to perform regular seasons there. Having first-hand experience of The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle and Swan Lake in large-scale productions at the Royal Opera House, the Metropolitan Opera House New York and the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, Grey understood the power of these ballets for the audience, and their importance for the prestige and development of a company. Therefore, negotiating seasons at the Coliseum where spectacular productions could be presented in an appropriately lavish environment seems like a significant step to us.

As performers, Alicia Markova, Beryl Grey and Peter Schaufuss were all international stars, intrepid individuals who went on to shape the repertoire of ENB by incorporating and highlighting specific traditions associated with their prestigious dancing careers, thereby contributing to the Company’s distinctive identity. In addition, as directors, Grey and Schaufuss launched major initiatives to bring a greater stability and sense of permanence to the Company: Grey secured Markova House as the Company’s first permanent home in 1976, while twelve years later Schaufuss, coming from one of the oldest ballet schools in the world, established English National Ballet School.

Concluding Thoughts on ENB Now and Then

In 1993 Pritchard wrote: “English National Ballet has never been a notably innovative company determined to challenge its audience” (450). Sixteen years later Sanjoy Roy made a similar comment, but framed it in more specific terms, portraying the decision not to challenge audiences as a pragmatic choice: “Like many other big ballet companies, ENB is cautious about programming too many modern works in case it loses audiences”.

In January 2020 however, at the English National Ballet Gala Celebration, the Company that we witnessed hardly seemed to be “cautious about programming” or unwilling to “challenge its audience”. The celebration garnered glowing reviews attesting to both the strength and vigour of the dancers, and the diversity and richness of the repertoire (Gaisford; Guerreiro; Watts; Weiss). For us the Gala marked not only seventy years of Company history, but also over seven years of Tamara Rojo’s leadership. We not only witnessed a company at the top of its game, but were excited about the inventive and well-laid plans for the future, as ENB entered a new phase of development with brand new purpose-built premises.

As we all know, the year has not gone to plan for any of us. Nonetheless, with its forthcoming digital season, including works by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Russell Maliphant and Stina Quagebur, it would be difficult to recognise the Company in its current form from the words of Pritchard and Roy. In our opinion it has now evolved into an innovative company that frequently challenges its audiences with unfamiliar movement and music styles, and subject matter, while still “delighting them with the traditional” (English National Ballet 4). And in keeping with the optimism of their new address on Hopewell Square, we believe that ENB will continue to fulfil its vision of “celebrat[ing] the tradition of great classical ballet while embracing change, evolving the art form for future generations and encouraging audiences to deepen their engagement” (5).

Next time on British Ballet Now and Then … This season English National Ballet planned a restaging of Marius Petipa’s 1898 Raymonda based on a retelling of the narrative with Florence Nightingale at its heart. In response to this we will consider how British ballet choreographers and directors have ensured the continuing relevance of ballet as an art form.

© British Ballet Now and Then

References

Anderson, Zoë. “Marguerite and Armand”. Independent, 13 Feb. 2013, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-dance/reviews/marguerite-and-armand-the-royal-ballet-sergei-polunin-and-tamara-rojo-royal-opera-house-london-8492773.html. Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

Bland, Alexander. The Royal Ballet: the first 50 years. Royal Opera House, 1981.

Brown, Ismene. “Rojo is Queen of the Swans”. The Telegraph, 29 Nov. 2002 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/dance/3586430/Rojo-is-queen-of-the-Swan-Queens.html, . Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

Byrne, Emma. “English National Ballet/Le Corsaire review: A swaggering, bravura spectacle”. Evening Standard, 9 Jan. 2020, English National Ballet/Le Corsaire review: A swaggering, bravura spectacle. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Crompton, Sarah. “Review: Giselle (English National Ballet, London Coliseum)”. WhatsOnStage, http://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/reviews/giselle-english-national-ballet-coliseum_42636.html. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

—. “Radiant Rojo Brings Fairytale Alive”. The Telegraph, 13 Nov. 2006, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/dance/3656529/Radiant-Rojo-brings-fairytale-alive.html. Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

“Desert Island Discs: Dame Beryl Grey”. BBC Radio 4, 10 Mar. 2002, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0094805. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Dodge, Laura. “Birmingham Royal Ballet’s Sleeping Beauty – a lavish production of a magical fairy tale. bachtrack, 20 Oct. 2013, https://bachtrack.com/review-oct-2013-birmingham-royal-ballet-sleeping-beautny-sadlers-wells. Accessed 7 Aug. 2020.

English National Ballet. Annual Review 2017-2018. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

Franks, A. H., The Girls’ Book of Ballet. Burke, 1960.

Gaisford, Sue. “English National Ballet 70th Anniversary Gala, Coliseum review – a fine celebration. The Arts Desk, 22 Jan. 2020, https://theartsdesk.com/dance/english-national-ballet-70th-anniversary-gala-coliseum-review-fine-celebration. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

“Giselle recording with Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin”. YouTube, uploaded by English National Ballet, 16 Jan. 2017, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7HnNXvF0Kn0&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 18 Sept. 2020.

Gilbert, Jenny. The I newspaper, 9 Jan. 2020, https://inews.co.uk/culture/arts/le-corsaire-london-coliseum-review-this-flamboyant-ballet-is-a-tonic-for-the-january-blues-english-national-tickets-383518. Accessed 9 ug. 2020.

Grey, Beryl. For the Love of Dance. Oberon, 2017.

Guerreiro, Teresa. “ENB’s anniversary gala review”. CutlureWhisper, 18 Jan. 2020, http://www.culturewhisper.com/r/dance/english_national_ballet_anniversary_galas_coliseum/14791 Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

Hall, George A. London’s Festival Ballet Annual 1956-57. Gray’s Inn Press, 1957.

Jays, David. “Giselle review – Alina Cojocaru is sublime in signature role”. The Guardian, 12 Jan. 2017, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2017/jan/12/giselle-coliseum-london-english-national-ballet-review-alina-cojocaru. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

Jennings, Luke. “English National Ballet: The Sleeping Beauty review – a way with the fairies”, The Guardian, June 2018, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/jun/10/english-national-ballet-sleeping-beauty-review-alina-cojacaru. Accessed 7 Aug., 2020.

—. “Giselle Review – Xander Parish Steals the Show”. The Guardian, 22 Jan. 2017, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2017/jan/22/giselle-review-english-national-ballet-coliseum-xander-parish-laurretta-summerscales. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

—. “Step into the Past”. The Guardian, 12 Mar. 2006, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2006/mar/12/dance. Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

“JoBurg Ballet Offstage: Tamara Rojo”. Instagram, 30 July 2020, http://www.instagram.com/tv/CDRo3OtFI1o/?igshid=up23dsd6movc. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Pritchard, Jane. “English National Ballet”. The International Dictionary of Ballet, edited by Martha Bremser, St James Press, 1993, pp. 450-5.

Mackrell, Judith. “Giselle”. The Guardian, 15 Jan. 2004, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2004/jan/15/dance. Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

—. “Giselle- a Romantic Ballet”. English National Ballet, Programme, Belfast, 2017.

—. “Song of the Earth/La Sylphide review – Rojo powers a demanding double bill”. The Guardian, 10 Jan. 2018, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/jan/10/song-earth-sylphide-review-coliseum-london-english-national-ballet-rojo. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

Roy, Sanjoy. “Step-by-step guide to dance: English National Ballet”. The Guardian, 16 Jun. 2009, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2009/jun/16/guide-dance-english-national-ballet. Accessed 16 Sept. 2020.

“THE SLEEPING BEAUTY LIVE from the Royal Ballet”. YouTube, uploaded by More2Screen, 8 Nov. 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuncvxSDIiY&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 7 Aug. 2020.

Speer, Dean. “Pacific Northwest Ballet: the pinnacle”. CriticalDance, 2 Feb. 2019, https://criticaldance.org/pacific-northwest-ballet-pinnacle/. Accessed 7 Aug. 2020.

“‘Les Sylphides’ Part 1”. YouTube, uploaded by John Hall, 31 Aug. 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EqKyGBbYNXs. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

“‘Les Sylphides’ Part 2”. YouTube, uploaded by John Hall, 31 Aug. 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AelTZYoc2_U&t=44s. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

“Tom and Ty Talk: ‘Ballet is honest’ with Tamara Rojo”. Tom and Ty Talk, 19 June 2020, https://pod.co/tom-and-ty-talk. Accessed 19 July 2020.

Watts, Graham. “English National Ballet’s Exceptional Giselle”. Backtrack, 14 Jan. 2017, https://bachtrack.com/review-giselle-skeaping-cojocaru-english-national-ballet-coliseum-london-january-2017. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

—. “Review – English National Ballet – Giselle – London Coliseum”. Londondance, 23 Jan. 2017, http://londondance.com/articles/reviews/english-national-ballet-giselle-london-coliseum-1/. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

—. “Review: Royal Ballet – The Sleeping Beauty – Royal Opera House”. Londondance, 24 Feb. 2014, http://londondance.com/articles/reviews/royal-ballet-sleeping-beauty-2014/. Accessed 6 Sept. 2020.

—. “A roller-coaster of diverse dance as English National Ballet celebrates its 70th anniversary”. Bachtrack, 19 Jan. 2020, https://bachtrack.com/review-english-national-ballet-70-anniversary-gala-coliseum-london-january-2020. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

Weiss, Deborah. “English National Ballet – 70th Anniversary Gala – London”. DanceTabs, 20 Jan. 2020, https://dancetabs.com/2020/01/englishnational-ballet-70th-anniversary-gala-london/. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

Winship, Lyndsey. “English National Ballet: Le Corsaire review – firecracker dancing”. The Guardian, 9 Jan. 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/jan/09/english-national-ballet-le-corsaire-review-firecracker-dancing. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.