THE MOTH AND THE BUTTERFLY

The ballet A Streetcar Named Desire (2012) begins and ends on a dimly lit stage with Blanche Dubois reaching up towards a lightbulb to the sound of an eerie, unnerving tremolo on the strings. Moth like, her fragile body is torn between desire and caution, her fluttering hands betraying her extreme vulnerability, her sharp withdrawals from the light accentuating her fear.

The ballet Broken Wings (2016) begins with Skeletons sitting on and leaning against a large black box, which represents different spaces in Frida Kahlo’s life through the course of the work. Frida arises from the dark cube, aided by the Skeletons. The ballet ends with her encased in the same construct, but now opened to reveal a vibrant orange, red and yellow butterfly inside, to which Frida forms the centre. After the black box is closed by the Skeletons, a brightly coloured bird emerges and turns continuously as the curtains close, fluttering into eternity, as it were.

Both of these ballets were choreographed by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, whom we introduced to our readers in one of our early posts, Female Choreographers Now and Then. Although based in Amsterdam, Lopez Ochoa works for ballet companies across the globe—from Seattle to Cuba, Estonia to Australia. The two works that form the basis of this post, however, were both created for British ballet companies. Former Artistic Director of Scottish Ballet Ashley Page commissioned Streetcar, while Broken Wings was choreographed as part of English National Ballet’s 2016 She Said programme, commissioned by Tamara Rojo, and comprising three new works by female choreographers. In both cases Lopez Ochoa worked with the theatre and film director Nancy Meckler, which highlights for us the centrality of characterisation, narrative and drama in these ballets.

On the face of it, Tennessee Williams’ fictional Blanche and the artist Frida Kahlo have little in common. But we are fascinated by the imagery used by Lopez Ochoa that tempts us to make comparisons that we would otherwise undoubtedly have failed to notice.

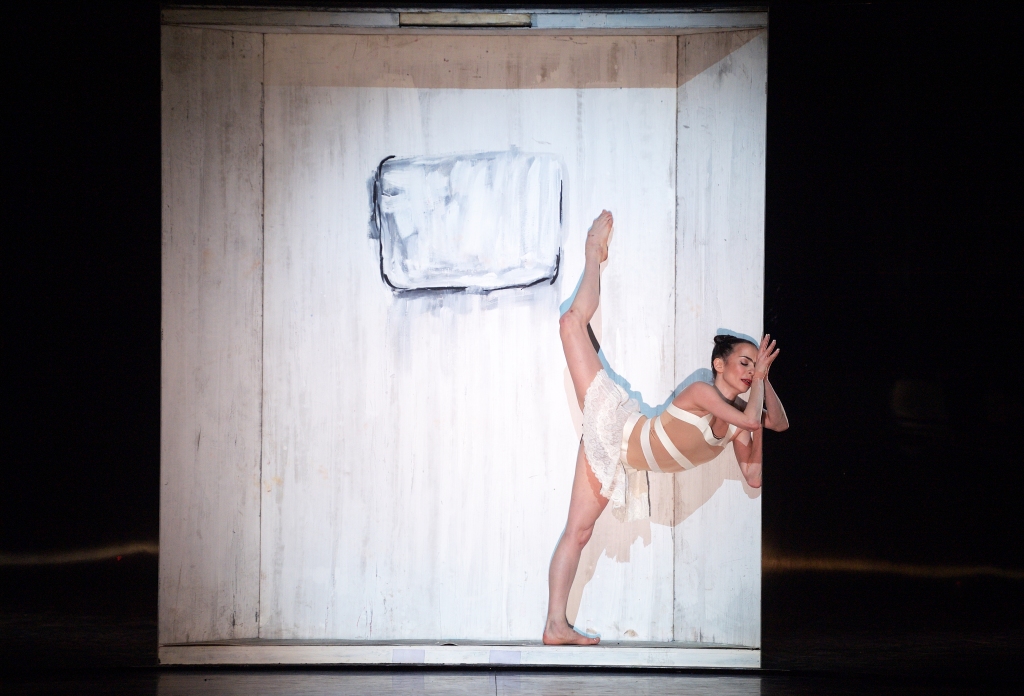

© Andy Ross

Loss

The three protagonists of Williams’ play are Blanche, her sister Stella, and Stanley, Stella’s husband. Set in the New Orleans of 1947, the year in which Williams wrote his play, the action takes place in the claustrophobic atmosphere of Stella’s apartment where Blanche has come to escape her old life. Blanche is trapped by memories of the past, combined with a fantasy world of her own imagination. The story of Blanche’s past and the losses that she has incurred are revealed gradually, bit by bit, as the play progresses. In contrast, Lopez Ochoa’s ballet depicts Blanche’s life chronologically, beginning with her wedding as a young girl, which visibly portrays her as the “tender and trusting” character that Stella describes to Stanley (Williams 81).

But the joyous wedding is followed by a brutal stream of losses occurring one after the other in unremitting succession. First comes the suicide of Blanche’s young homosexual husband, Allan, for which she feels an inescapable, hounding guilt, demonstrated by his haunting blood-stained reappearances through the course of the work. After Stella leaves for New Orleans, their relatives disappear from the tableau of the family photograph, represented by the cast collapsing one after the other with a sickly inevitability. The structure of Blanche’s life as she knows it finally gives way with the loss of Belle Reve, the ancestral home, which without warning, suddenly disintegrates block by block, crashing to a pile on the floor. For Marge Hendrick, one of Scottish Ballet’s Principals who performs Blanche, this approach to communicating the narrative explains the reasons for Blanche’s behaviour (qtd. in O’Brien 15). Hendrick further asserts, “We can see her in her best light at the start, and really see the decline, which is progressive” (1:14-1:23). And for us, this means that we are seeing the narrative through the eyes of Blanche: Lopez Ochoa has given her a “voice”.

Kahlo’s life is also depicted as a chronology in Broken Wings. After her “birth” from the black box, a structure that is central to the narrative and, as noted, symbolises various locations and aspects of Kahlo’s life, she meets her first love, who is with her when she experiences the accident that will change her life forever, causing permanent damage to her spine and pelvis. The severity of her injuries impacts on her ability to bear children, and leads to a series of operations over the course of almost three decades. Like the loss of Belle Reve, Kahlo’s accident is depicted vividly and symbolically. Four of the Skeletons, two moving towards Frida’s front and two towards her back, form a line that travels through her centre, representing the bus handrail that pierced right through her pelvis. The slow motion of the action reflects Kahlo’s own memory of the incident: “It was a strange crash, not violent but dull and slow” (qtd. in Svoboda). The Skeletons place her inside the black box, now transformed into the hospital.

Response to loss

Lopez Ochoa and her collaborator Meckler leave us in no doubt as to the impact of loss and guilt on Blanche in Streetcar. Living a lonely, haunted life alone in a hotel room, she turns to alcohol to escape from her savage memories, and to promiscuity (“intimacies with strangers”, as she describes it in the play) to fill her “empty heart” (Williams 87). In dance critic Sara Veale’s pithy words, we witness Blanche “drowning her sorrows with bottle after bottle and stranger after stranger”. Hendrick sees the sexual encounters, conveyed with a sensual, tactile fluidity, as “the only thing that makes her feel alive” (1:03-1:06). But the garish neon hotel sign accentuates the insalubrious nature of Blanche’s pitiful existence, as well as the impersonal atmosphere of the environment. The scene makes for a drastic contrast to the warmth of the “soft and sprightly” duet for Blanche and Allan back at Belle Reve (Veale). This chapter of Blanche’s life culminates in inappropriate sexual behaviour with a minor, for which she is driven out of town “by a chorus of disapproving, stomping grey people” (Parry). This aggressive crowd is patently devoid of the empathy the creators of the ballet wish us to feel for Blanche.

And so Blanche arrives in New Orleans in the hope of starting a fresh life. Her actions reveal her insecurity: she surreptitiously swigs from a bottle, flirts demurely with Stanley, and takes a bath as if she can cleanse herself of her recent past. But the image that she presents is based on her young affluent life, her upbringing as a Southern belle, and consequently clashes harshly with her new environment. On entering Stella and Stanley’s apartment, she scans the room with visible dismay and swipes the dirt uneasily from her hands. Blanche’s genteel demeanour and the stylish wardrobe she has brought with her belong to the world of her youth, a world to which she retreats to preserve her sense of self-worth and dignity. Towards the end of Act II she wears a deep fuchsia gown, made of heavy silk and covered with rhinestones and diamantes, behind which she can indulge in her memories and in her fantasy world, where she is a gentlewoman of great refinement and respectability, with a host of admirers. Eve Mutso, who created the role of Blanche, comments on the symbolism of the dress: “You can’t see through this dress: it’s a cover; it’s a façade she puts on. And it’s fake” (9:45-9:50).

Like Blanche, Frida too must begin a fresh life after the accident that creates such a devastating impact on her health. In the hospital interior of Broken Wings’ black cube—white, cold, impersonal— we witness Frida’s despair, the paralysis of her trauma, her physical pain and feelings of hopeless entrapment imposed upon her by the two-dimensionality of her surroundings. But from this clinical environment is born Frida’s life of imagination, as her paintings are brought into three-dimensional life by a group of 11 Male Fridas, sporting billowing full-length ruffled skirts in bright, contrasting colours, inspired by traditional Tehuana dress. Their headdresses include flowers, butterflies, antlers, and the ceremonial resplandor. Through their reference to Kahlo’s self-portraits, such as Self-Portrait with a Monkey (1948), Self-Portrait with a Necklace of Thorns (1940), and Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (1943), these costumes, designed by Dieuweke van Reij, simultaneously refer to Frida’s iconic dress style and to her phenomenal imagination and talent as an artist. As the Male Fridas swirl and sway with bold lunges and leaps, and expansive leg gestures, they make full use of their skirts, creating a riot of colour and energy, filling the stage with Kahlo’s own peculiar union of masculinity and femininity. Frida now strides purposefully out of the black box, dressed in an orange Tehuana skirt to dance in the same style. She is held aloft by the Male Fridas, dances in unison with them, and boldly leads and directs their movements.

© Laurent Liotardo

The strength of Frida’s imagination comes to her aid again after she endures a miscarriage, portrayed on stage with a red cord reminiscent of her painting Henry Ford Hospital (1932). Now the cube becomes a blood-bespattered hospital room in which she cowers after her desperate struggle to keep hold of the cord, which is inevitably wrenched from her grasp by one of the Skeletons. But in spite of the pain that engulfs her being, she is distracted by leaves creeping through the gap between the door and frame of the cube, as if they are growing through an open wound, making us think of Roots (1943), in which Kahlo is “stretched out on the ground dressed in her Tehuana costume, with leafy green stems full of sap, emerging from her chest and taking root in the arid, fissured landscape” (Burrus 90). Significantly, this painting, such a rich evocation of rebirth, depicts Kahlo in an orange skirt, the colour of Frida’s skirt in Broken Wings. And indeed the leaves emerge as fantastical creatures, who gradually entice Frida out of the box again.

For both Frida and Blanche fantasy becomes integral to their survival. As an unmarried, unemployed woman with no family apart from her sister, Blanche is both suspect and vulnerable. To survive she needs a husband, so the fantasy she creates about her life is in part to this end, even telling Stanley’s friend Mitch, a prospective spouse, “I don’t want realism … I’ll tell you what I want. Magic!” (Williams 86). Blanche sees Mitch as “a cleft in the rock of the world that I could hide in” (88). Like the moth, which Williams considered for the title of the play, she avoids the light of reality.

In contrast, the fantasy of Frida’s life is of an entirely different ilk: it is not Kahlo’s way of hiding from the world; rather it is her way of coping with the catastrophes that beleaguer her, making sense of her troubled life through drawing from the treasure trove of her prodigious talent. Kahlo “paint[s] her reality”, as art writer Christina Burrus emphasises by quoting the artist’s own words in the subtitle of her biography of Kahlo: images inspired by bodily and emotional torture share the canvas with symbols of the natural world and the manufactured world. In Broken Wings Frida’s reality is communicated not only through the choreography of suffering, but through her costume based on The Broken Column (1944), in which Kahlo’s damaged body is held together by a brace, and later through the figure of The Deer, who is pierced by an arrow, referring to the 1946 painting The Wounded Deer.

The Presence of death

Just as tragic loss and harsh reality connect Blanche and Frida, so does the constant presence of death.

The Skeletons, present at both the start and end of Broken Wings, make regular appearances throughout the course of the ballet, either actively observing or participating in the action. Ominous though this may sound, and it is ominous, they are often rather comical characters, lounging against the black box in their boredom, playing with a ladder, cavorting with sombreros, mimicking guitar playing; and when they interfere too much, Frida gives them a sharp rap over the knuckles.

This is not only a reflection of Frida’s feisty spirit, but also of her culture. In Mexico death is perceived as a part of everyday life (Burrus 77), and traditions connected to the Dias de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), when people dress up as skeletons and have their faces painted as skulls, are laced with irony and humour (Ward). Having survived polio as a child and escaped the eager clutches of death in her near-fatal accident, Frida seems to have the upper hand over death. At the end of the ballet two of the Skeletons slowly fold the doors of the box shut, and as the brightly plumaged bird bourrées around and around atop the black cube, Kahlo’s own words come to mind: “Nothing is absolute. Everything changes, everything moves, everything revolves, everything flies and goes away” (qtd. in Almeida).

Reminders of death in Streetcar Named Desire escalate not only through the recurring appearance of Allan in his blood-drenched shirt, but through the lone Mexican Flower Seller from Act I multiplying into a corps de ballet of dark figures carrying flowers for the dead in Act II.

Dance critic Judith Mackrell describes the “horror” of the rape scene in the ballet as “focused not on the act of penetration but on the preceding struggle, during which Blanche is stripped, manhandled and degraded by Stanley to become an abject thing”. That Blanche is stripped is significant: she is robbed of her fuchsia gown, which has enabled her to hide from reality and given her some sense of hope and identity. Now, having been reduced to an “abject thing”, she no longer has the capacity to cope with real life at all. Although Blanche has not experienced a death that takes her physically from this world, this metaphorical death creates the final irreversible rift between herself and the reality of the world around her—a reality that has passed sentence on her but has acquitted her assailant.

Through the vision of Lopez Ochoa, we come to understand how the “tender and trusting” young Blanche becomes the doomed moth of Tennessee Williams’ play.

Equally our eyes are opened to the butterfly that is Frida Kahlo, reborn and transformed in all her glory: vulnerable and ephemeral, but with the capacity for rebirth and transformation through the life of her creations.

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

Almeida, Laura. “Quotes from Frida Kahlo”. Denver Art Museum, 28 Dec. 2020, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/blog/quotes-frida-kahlo.

Burrus, Christina. Frida Kahlo ‘I Paint my Reality’. Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Garcia, Peyton. “Inside the Fantastical World of Frida Kahlo”. RED, 8 Apr. 2022, https://red.msudenver.edu/2022/inside-the-fantastical-world-of-frida-kahlo/#:~:text=I%20paint%20my%20own%20reality,of%20Denver’s%20Department%20of%20Art.

Hendrick, Marge. “Scottish Ballet: A Streetcar Named Desire – Becoming Blanche”. YouTube, uploaded by Scottish Ballet, 8 June 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rG1aQDZiIFU&t=87s.

Mackrell, Judith. “A Streetcar Named Desire review – erotic and tragic ballet”. The Guardian, 1 Apr. 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2015/apr/01/streetcar-named-desire-sadlers-wells-scottish-ballet-review.

Mutso, Eve. “Scottish Ballet: A Streetcar Named Desire Uncut”. YouTube, uploaded by Scottish Ballet, 9 Mar. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUT7wJxzxKE&t=592s.

O’Brien, Róisín. “Getting Lost in the Story”. Programme for A Streetcar Named Desire, 2023, pp. 12-16.

Parry, Jann. “Scottish Ballet – A Streetcar Named Desire – London”. DanceTabs, 29 Apr. 2012, https://dancetabs.com/2012/04/scottish-ballet-a-streetcar-named-desire-london/.

Svoboda, Elizabeth. “How a Devastating Accident Changed Frida Kahlo’s Life and Inspired Her Art”. Sky History, 9 Mar. 2022, www.history.com/news/frida-kahlo-bus-accident-art.

Veale, Sara. “Real Magic”. Fjord Review, 2 Apr. 2015, https://fjordreview.com/blogs/all/scottish-ballet-streetcar-named-desire.

Ward, Logan. “Top 10 things to know about the Day of the Dead”. National Geographic, 14 Oct. 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/top-ten-day-of-dead-mexico.

Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire. Penguin Modern Classics, 2009.