Gender Fluidity Now

The Sleeping Beauty now

When the curtains rises on Marius Petipa’s 1890 The Sleeping Beauty, we are left in no doubt that we are entering a world of rigid codes in terms of clothing, etiquette, and hierarchy. And as the ballet progresses, we quickly become aware of its binary nature, with clear-cut distinctions between good and evil, beauty and ugliness, youth and age, male and female.

Based on Charles Perrault’s “old fairy”, the Evil Fairy Carabosse is indisputably female. Nonetheless, following perhaps the example of Old Madge in August Bournonville’s La Sylphide (1836), Carabosse was originally performed by the renowned virtuoso and mime artist Enrico Cecchetti, and is still frequently performed by a male dancer. Another contributory factor to this decision may have been the nature of Baba Yaga, the “supreme scare figure of the Russian nursery”, who in mythographer Marina Warner’s words “breaks the laws of nature. Baba Yaga isn’t quite a woman, and certainly not feminine; there’s something of Tiresias about her, double-sexed and knowing” (more about Tiresias in the Then section of this post).

Writing in 1998, American historian Sally Banes describes Carabosse as “old, ugly, wicked, hunchbacked” (54). Clearly Carabosse is guilty of wickedness (although we are not given any explanation why), and her other attributes are implied through her name: bosse meaning hump or swelling, and cara meaning face. This is indisputably the archetypal figure of the ugly old crone (Warner; Watson; Windling).

Banes analyses the ways in which Carabosse flaunts all the codes integral to Sleeping Beauty’s court life:

She breaks the polite bodily codes of the courtiers. She takes up too much space; her movements are angular, spasmodic, and grotesque. She transgresses the boundary between female power seen as beautiful and good (as in the Lilac Fairy’s commanding presence) and female power seen as ugly and evil … Usually played by a man (like Madge in La Sylphide, symbolizing her distinctly unfeminine traits and behavior), Carabosse has all the wrong proportions, above all gigantic hands. She is a monster precisely because she is a category error, seemingly violating gender boundaries by combining aspects of male and female.

In this world a woman can be either powerful, good and beautiful or powerful, evil and ugly. However, not only is Carabosse ugly and evil, and old, but like Baba Yaga she simultaneously embodies an archetypal female stereotype and fails to adhere to ideals of femininity. And in this world of classical ballet, she is incapable of executing la danse d’école: “Unlike the good fairies, who balance confidently on one leg while dancing, she cannot even balance on two legs, for she walks with a cane” (Banes 54).

The Royal Ballet’s last run of Sleeping Beauty showcased a variety of female dancers in the role, including Kristen McNally, who has been performing Carabosse since 2009. Reviews of McNally demonstrate that in her interpretation, while the Evil Fairy may indeed be a monster by nature, she strays far from Banes’ description of Carabosse: Gerald Dowler describes her as “icily beautiful” with “an evil heart”, while Jann Parry sees her as similarly “glamorous and spiteful”. One of McNally’s predecessors Genesia Rosato, who performed the role in the first decade of this century, and is our favourite Carabosse, was perceived by reviewers not as “a grotesque old hag …, but a rather sexy and dangerous woman” (Titherington), a “beautiful fairy turned spiteful and gothic” (Liber).

Fortunately for us, both of these compelling performances are available commercially, so we were able to analyse the dancers’ movements closely in relation to Banes’ words and our knowledge of non-verbal communication and gender representation. As is characteristic of women, both Rosato and McNally walk with a narrower gait and keep their gestures rather closer to the body than do their male predecessors, such as Anthony Dowell and Frederick Ashton, and they use their canes to poke rather than beat the offending Catalabutte, who forgot to invite Carabosse to the Christening. Unlike the figure of the “ugly old crone” they walk upright, their skin is smooth, and their lips red; and there are no “gigantic hands”. Nonetheless we still see some “violation of gender boundaries” in their behaviour: they command the space around them; their gestures are strong, broad and intrusive, their eye contact ferocious. In fact their behaviour in general exhibits the kind of dominance more typical of men (Argyle 284; Burgoon et al. 381; Carli et al. 1031; Mast and Sczesny 414).

It seems clear that these renditions of Carabosse as glamorous and beautiful do not transgress the gender binary in the way that Banes has in mind, even though some masculine traits are visible. However, for us, the critical point about gender here is that in this particular world of Sleeping Beauty, a woman can be powerful and evil … and yes, beautiful.

Over at English National Ballet, who last performed The Sleeping Beauty in 2018, Kenneth MacMillan’s 1986 production provides a different, but equally fascinating, lens through which to view Carabosse, thanks to the costuming of Nicholas Georgiadis. Luke Jennings’ colourful description of Carabosse with her “sallow features and madly crimped [red] hair” is an unmistakable reference to Queen Elizabeth I, so renowned for her combination of masculine and feminine traits.

In 2018 casts included both male and female performers. Clearly, from critic Vera Liber’s point of view, there was a noticeable distinction between the interpretations of the first and second casts, one male, one female:

On first night, James Streeter revels in playing up the panto villain, giving it plenty of gothic largesse, whereas second cast Stina Quagebeur is a deliciously spiteful Nicole Kidman lookalike, a vengeful woman wronged.

Even though not explicit, the comparison with a female actor and choice of words “deliciously spiteful” and “vengeful woman” do strongly imply that, to Liber, Stina Quagebeur appears markedly more feminine than James Streeter. And her depiction of Quagebeur’s Carabosse is very much in line with the descriptions of Genesia Rosato and Kristen McNally in the role, combining evil, beauty and power.

What Carabosse and Elizabeth I have in common is that they both have the power to wreck the dynasty: Elizabeth through her choice not to bear children, and Carabosse by scheming to prevent Aurora from producing an heir. And this parallel with Elizabeth informs our understanding of Carabosse as a character that does not fit comfortably within a single gender category.

The Scottish preacher and author John Knox (1514-1572) declared that “God hath revealed to some in this our age that it is more than a monster in nature that a woman should reign and bear empire above man” (2). So whether performed by a male or female dancer, this Elizabeth-Carabosse can been seen as “a monster … seemingly violating gender boundaries”. And on a personal note, we would have to say that Stina Quagebeur is without a doubt the most terrifying Carabosse we have ever encountered.

Cinderella now

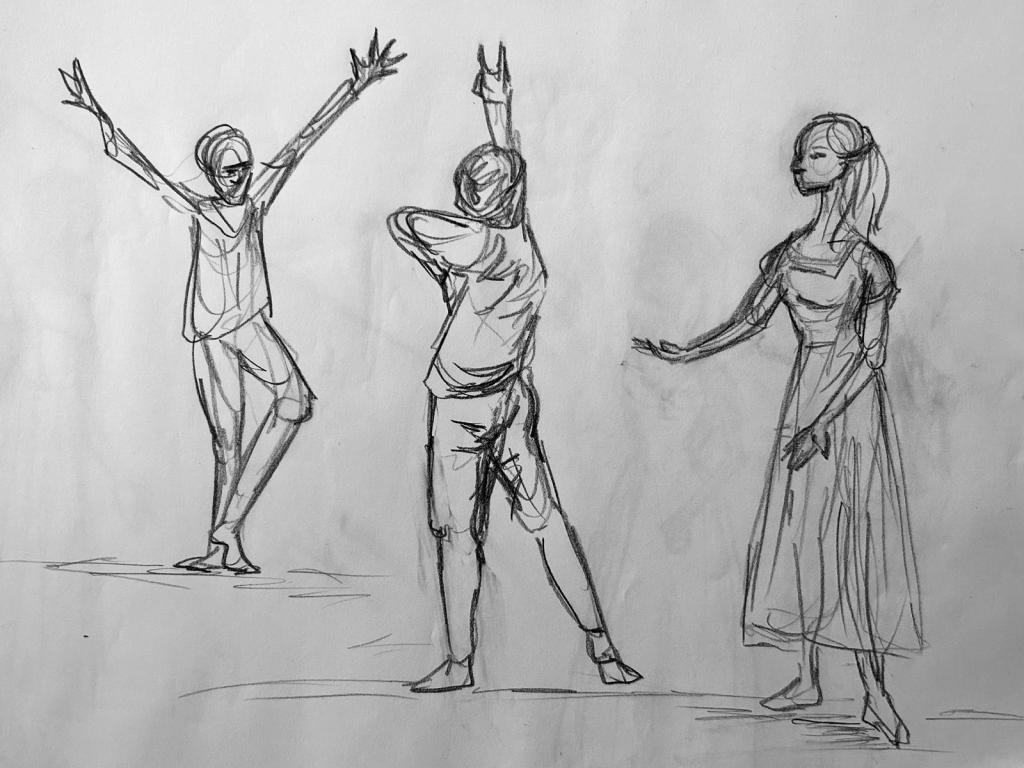

Last season Scottish Ballet explored gender fluidity, again in the context of a familiar, well-loved fairy-tale ballet, but in an unusual and innovative way.

Renamed Cinders! the narrative of Cinderella on some nights featured the usual female Cinders, who falls in love with the Prince, while on others, romance blossomed between a male Cinders and the Princess.

The cast was deliberately not released in advance, so each audience remained uncertain of Cinders’ gender until their appearance on the stage. Consequently, when purchasing tickets, audiences had at least to be open to the challenge of a new way of viewing the work.

Scottish Ballet describes Cinders! as “an evolution and adaptation of Christopher Hampson’s [2015] Cinderella”. Given ballet’s rigid gender codes in terms of roles, behaviours, technique and vocabulary, you may, like us, be wondering how such a gender swap could ever be achieved. Critic Kathy Elgin asks with apparent consternation, “Would a man have to cope with girly bourrée-ing?”. Evidently, however, the adaptations were far more subtle than these musings suggest, as Elgin asserts that “the choreography is much the same irrespective of who’s playing what, except for some obvious variation in solos to accommodate male / female specialities. That is, in pas de deux, each is dancing the steps they would have danced in any pairing”. Yet despite the subtlety of the changes, it is clear that for both dancers and viewers the approach to characterisation made a substantial difference, resulting in fresh insights into of the nature of the protagonists.

Principal Dancer Bruno Michiardi reflected on the rehearsal process:

What I’ve found most interesting about the fluidity of the roles of the Cinders leads is just how different and new it’s made the ballet feel. We all know and love the classic story of Cinderella, but this new version means we’re suddenly working in this amazing upside-down realm, where the male part (previously a more traditionally stoic character) is a complex mixture of vulnerability and resilience, and the female role (usually quite timid and downtrodden for most of the original ballet) is empowered and full of charisma… I’m excited at the prospect of exploring this further and sharing that with the audience! (“Introducing Cinders”)

Reviewer Tom King sees this exchange of gender as a “re-written … dialogue of the dance between the Princess and Cinders … so the gender prominence of this work now changes completely too as it is the male lead who now dominates and performs so much of this ballet”. In contrast Elgin notes that “the commanding style of a princess in her own right reminds us how rarely women get the chance to make that kind of confident statement”.

These different perspectives highlight what is most important to us about the Cinders! gender swap—that is, the opportunity for both dancers and audience to reappraise how they perceive gender roles within the context of a traditional ballet narrative.

Broken Wings and the Male Fridas

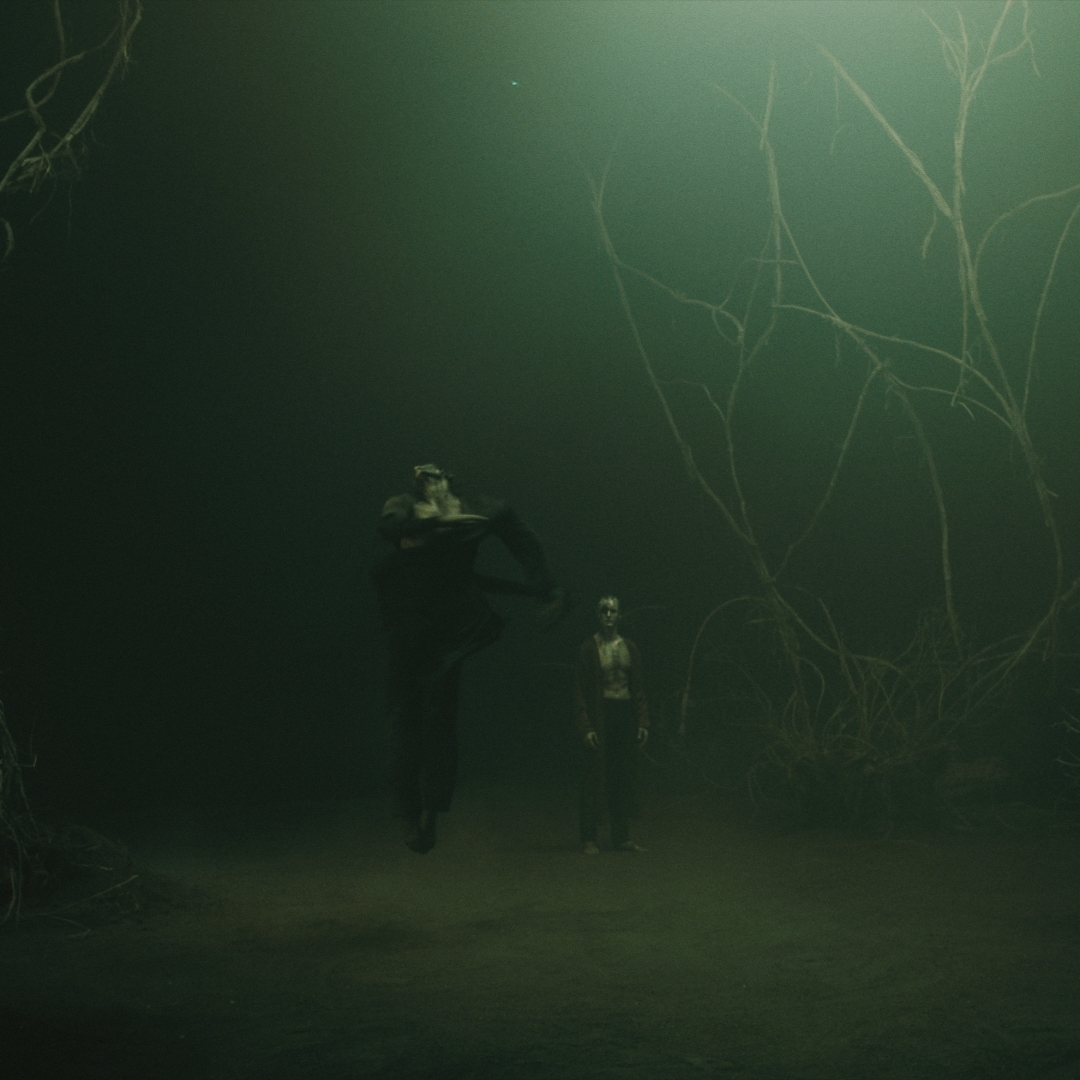

In 2016 choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa created a very different world to that of The Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella for English National Ballet. Based on the life of artist Frida Kahlo, this ballet presents gender fluidity in a unique way—unique, but completely in line with Kahlo’s life and art.

Like Queen Elizabeth I, Kahlo was known for her own peculiar union of masculinity and femininity. In the ballet this is perhaps most notable through the presence of eleven “Male Fridas” who bring Kahlo’s paintings into three-dimensional life.

Performed by male members of the company, these Fridas, described by designer Dieuweke van Reij as an “extension of Frida herself”, sport billowing full-length ruffled skirts, in bright, contrasting colours, inspired by traditional Tehuana dress. Their headdresses include flowers, butterflies, antlers, and the ceremonial resplandor, referencing specific self-portraits by Kahlo, including Self-Portrait with a Necklace of Thorns (1940), Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (1943), and Self-Portrait with a Monkey (1948). Their torsos are painted to match their skirts.

The costumes are inspired by Kahlo’s iconic dress style, which is undeniably feminine, with the soft folds of the material and decorative headdresses. But Kahlo was also known for a more androgynous style of dressing: even as a teenager she was known to wear a man’s suit with waistcoat and tie, and in her 1940 Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair she has cut her hair short and wears a man’s dark suit. Her monobrow, moustache and strong features were also celebrated, even exaggerated, in her paintings. And neither in terms of her behaviour did Kahlo conform to stereotypical femininity, with her forthrightness, her revolutionary politics, and her sexual appetite for both female and male lovers. But despite the evident femininity of the Broken Wings costumes, they also connote power. This is because the Tehuana dress is the traditional dress of the Zapotec women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, who are unconventional in being considered, to some extent at least, a matriarchal society, and from which, significantly, Kahlo’s mother hailed.

As the Male Fridas swirl and sway with bold lunges and leaps, and expansive leg gestures, they make full use of their skirts, creating a riot of colour and energy. And Frida joins them, dressed in an orange Tehuana skirt, dancing in the same bold but non-gendered style, sometimes in unison. Her dominance is writ large as the Male Fridas hold her aloft, and she boldly leads and directs their movements, displaying Kahlo’s own peculiar fusion of masculinity and femininity.

© Tristram Kenton

Further, the non-binary nature of the “Male Fridas” is accentuated by their strong resemblance to the “muxes” of Zapotec culture. The muxes are considered neither female nor male, but instead are a recognised third gender. While they are assigned male at birth, as adults they exhibit more stereotypically female attributes in their behaviours, and economic and societal roles. This can be seen, for example, in the way they dress, their skill at embroidering and weaving, and their caregiving to elderly relatives (Balderas; Plata).

And now we return to The Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella to discover how gender fluidity manifested itself in British ballet in the past, before exploring a less conventional work …

Gender Fluidity Then

The Sleeping Beauty then

As we said in the Now section of this post, in 1890 Marius Petipa created the character of Carabosse for Enrico Cecchetti. However, it’s interesting that when Sergei Diaghilev mounted his production of The Sleeping Beauty in London in 1921, Carabosse was performed by Carlotta Brianza, the originator of the role of Princess Aurora. Over the last century there have been phases of male and female Carabosses, and following the lead of Petipa and Diaghilev, the calibre of dancers has sometimes been extraordinary, including Frederick Ashton, Robert Helpmann, Monica Mason, Lynn Seymour, Anthony Dowell, Edward Watson and Zenaida Yanowsky.

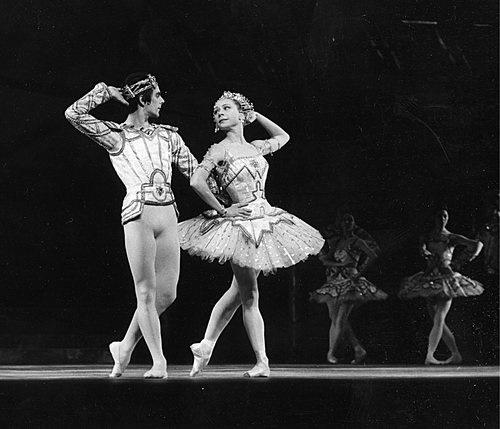

While it’s of interest that Brianza performed Carabosse for Diaghilev, it’s even more fascinating that it was not the role of Carabosse that the Impresario originally had in mind for Brianza; rather, it was her original role of Princess Aurora (Christoudia 201). By 1921 Brianza was in her mid-50s. According to the drama The Ballerinas, it was Brianza herself who suggested that she perform the part of the Evil Fairy. It would be understandable if Brianza had considered herself unsuitable for Aurora at this point in her career (Tamara Rojo famously stated that she believed ballerinas should not be performing Aurora beyond the age of forty, and the first night went to the 26-year-old Olga Spessivtseva). Ironically though, Carla Fracci, who performs sections of Aurora’s choreography as both Brianza and Spessivtseva in the programme, was herself just shy of fifty when it was recorded, and we would defy anyone to say she looks anything but youthful in both her appearance and her dancing. At the 1890 premiere designer Alexander Benois described Brianza as “very pretty”, while reviews highlighted her grace and elegance (qtd. in Wiley 189). Perhaps the most celebrated photograph of Brianza as Aurora shows her balancing sur pointe in cou de pied, her hands placed demurely by her neck, so that her forearms partially hide her décolleté, and attired in a tutu that gives her the perfect wasp-like waist. The picture of femininity. There seems no logical reason then that in her 50s Brianza would have lost all of her beauty, grace and elegance.

It is difficult to know what Brianza was like as Carabosse, but we were able to find a small number of photos of her in the role, which make it crystal clear that Carabosse in this production was bereft of beauty, grace and elegance. One photo shows her surrounded by her entourage of rats that seem to tower over her, making her appear a rather petite figure, her stature diminished by her hunched back and lankness of her hair (“Carlotta Brianza as Carabosse”). Feminine, but hardly the ideal of femininity. In another she is seems to be mistress of all she surveys. The stoop and the lank hair are still in evidence, but her silhouetted profile brings a baleful mystery to her lone, and in this image androgynous, figure (MacDonald 280).

Luckily, however, we have a very good idea of how Carabosse was portrayed in the 1950s by the Royal Ballet in the celebrated 1946 production by Nicholas Sergeyev and Ninette de Valois, thanks to two recordings of the work, made in 1955 and 1959. On opening night Robert Helpmann accomplished the astonishing feat of performing both Carabosse and the Prince. However, it is Ashton who appears in the 1955 recording, while the 1959 film features Yvonne Cartier, who by this time was focussing on mime due to an inoperable ankle injury.

© Royal Academy of Dance / ArenaPAL

Even though these two performances feature a male and a female dancer, they both exhibit a remarkable likeness to the image of Carabosse that we outlined in the Now section of this post. With their blemished skin and stooping gait both Ashton and Cartier display the attributes of the archetypal “ugly old crone” or “grotesque old hag”. More particularly, the words of Sally Banes could have been written specifically for these renditions of the Evil Fairy: Ashton’s movement are indisputably “angular, spasmodic, and grotesque”, while Cartier spreads her arms wide like enormous wings, and as a result “takes up too much space”. And they have “the wrong proportions”. Ashton has an exaggerated prosthetic nose, and they both have “gigantic hands” due to their long fake nails, threatening gestures, and in the case of Cartier, the spreading of her fingers like a raptor’s talons.

© Royal Academy of Dance / ArenaPAL

It seems that not even Brianza, the hyperfeminine Aurora of 1890, could escape the curse of being transformed from benign and pulchritudinous to malevolent and unsightly. But as we have seen, the figure of Carabosse has evolved quite drastically over the last decades of the 20th century and into the current century, challenging the binaries of female vs. male, ugliness vs. beauty, good vs. evil. How will that evolution continue, we wonder?

Cinderella then

The Royal Ballet’s decision to cast female Stepsisters as well as the traditional male Stepsisters in their 2023 production of Ashton’s Cinderella caused quite a stir (“Ashton’s Cinderella”; Pritchard), and we were excited about this “new” development. However, we soon discovered that it had been Ashton’s original intention to create his choreography on female dancers, more specifically on Margaret Dale (the pioneer ballet filmmaker) and Moyra Fraser. It was in fact Fraser’s unavailability that caused the change in plan, resulting in the celebrated Ashton-Helpmann Stepsister twosome.

Robert Helpmann and Frederick Ashton, 1965 © Royal Academy of Dance / ArenaPAL

Although critic Judith Mackrell has referred to the Stepsisters as “monsters”, in stark contrast to Carabosse, they are “monsters of delusional vanity” (“Girls Aloud”) rather than monsters of evil. Their behaviour and movements are noticeably “feminine”: they preen in front of the mirror, fuss about their clothes, bicker, walk in a flouncing manner and perform “female” variations at the Ball. These variations overtly reference typical vocabulary from classical pas for ballerinas: small sissonnes piqué arabesque into retiré, a series of pas de chat, développé à la seconde, emboîtés en tournant; they even include lifts and fish dives supported by their male partners. In fact the solo for the timid Stepsister, performed by Ashton, draws on the Sugar Plum Fairy variation, and perhaps also on Walt Disney’s hippo ballerina Hyacinth (Fantasia, 1940), inspired by the Baby Ballerina Tatiana Riabouchinska.

Further, there are additional layers of femininity to these characters. Firstly, with their exaggerated costumes and comedic manners, they recognisably reference the tradition of the Pantomime Dame, so familiar to audiences in this country. Secondly, Ashton had performed the Prince in Andrée Howard’s 1935 Cinderella, and according to David Vaughan (234) was influenced by some aspects of the characterisation, costumes and wig of the sister which Howard choreographed, designed and performed herself. And thirdly, both Ashton and Helpmann were known for their mimicry, notably of women, and both were said to have been influenced by specific “female eccentrics” (Kavanagh 365): Helpmann by Jane Clark (renowned for her feistiness) and comedienne Beatrice Lillie (Vaughan 234), and Ashton himself by Edith Sitwell (Kavanagh 365).

According to dance critic and historian David Vaughan, a female cast was unsuccessful, because “the kind of observation of the female character that lay beneath these performances could be achieved only by men” (234). However, we would argue that, as in the case of the Pantomime Dame, performers and audience share an understanding that the performers are male, and much of the humour resides in this shared understanding, despite the overt performative femininity: “The audience and the character comically share the knowledge that the Dame is not really a woman” (“‘It’s behind you!’”). And there must have been a delicious additional irony attached to the first cast at the premiere in 1948, given the status of both Ashton and Helpmann as key figures in the development of British ballet.

While the Sisters each perform a ballerina solo, their dancing is very poor in classical terms, with turned-in feet, shaky balance, poor coordination and spatial confusion. This of course adds to the humour of the work, a humour that perhaps loses some of its edge when these Pantomime Dames are performed by women. However, it also suggests that female characters who are not fully female, as it were, are in some way lacking, incapable as they are of performing female danse d’école, even when they are female dancers pretending to be male dancers pretending to be female.

© Royal Academy of Dance / ArenaPAL

Although Ashton and Helpmann were the most fêted “twin monsters” (Mackrell, “Girls Aloud”), the 1957 recording of the work featured Kenneth MacMillan instead of Helpmann. Writing about MacMillan’s performance, Peter Wright spotlights the humour that arises from the play on gender in this context:

Kenneth’s performance is remarkably considered, recognisably feminine but still decidedly masculine in the best tradition of pantomime dame … He was very funny. (149)

Tiresias

Happily, undertaking research for this post gave us the opportunity to discover more about a lesser known ballet by Frederick Ashton which, according to the Royal Opera House performance database, was performed only fourteen times over a period of four years after the premiere in 1951. Based on the titular figure from Greek mythology, Tiresias was a tale of sexual identity and pleasure, following the life of Tiresias, who was transformed from man into woman and then back to manhood as the result of his reaction to witnessing a pair of copulating snakes. Having experienced life as both man and woman, he is asked to decide the quarrel between Zeus and Hera as to whether males or females gain more enjoyment from the sexual act.

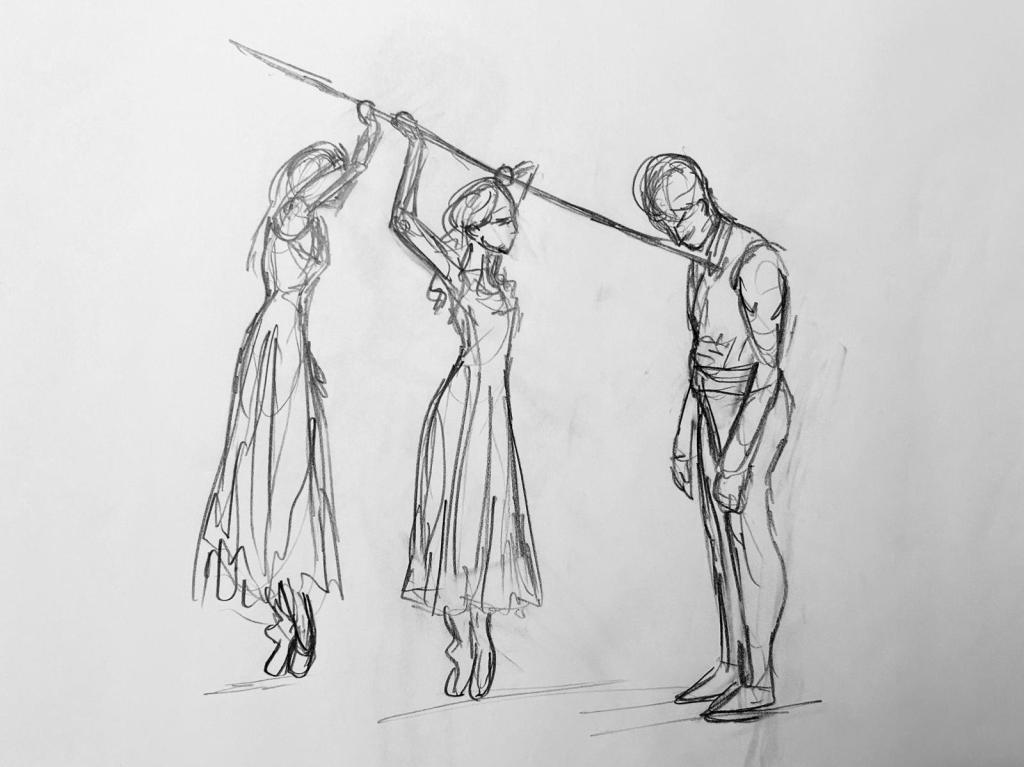

As we might expect from a ballet of this era, the eponymous Tiresias was not gender fluid in the way that Frida and her corps de ballet are in Broken Wings. Instead, Tiresias was performed by two dancers: Michael Somes as the male Tiresias, and Margot Fonteyn as his female counterpart. Nonetheless, David Raher, writing in The Dancing Times (15) after the premiere, made some comments about Fonteyn’s performance that are pertinent to our discussion:

Instead of contrasting femininity, she conveyed a masculinity in the attack and brio of her dancing. Incontestable evidence of her gender, however, lay in the soft yet firm arm placements and in the unsurpassed magic of controlled développés …

While we ourselves may not make the same gender associations as Raher, the critic’s commentary clearly demonstrates that he perceived aspects of male and female in Fonteyn’s performance.

David Vaughan, who also wrote Ashton’s biography, refers to the “wonderfully ambiguous eroticism” of the pas de deux (254), perhaps implying that the representation of gender is not as straightforward as is generally the case in ballet. Although there seems to be no publicly available video footage of the ballet, we have found some sources that suggest the sensual nature of the choreography: Julie Kavanagh’s description of the pas de deux as “fizz[ing] up into a kind of orgasm” (391), and John Wood’s photograph of Tiresias and her Lover (danced by John Field) showing them in a stylised pose of post-coital bliss, splayed across one another on the floor in a mirror image as they gaze into one other’s eyes.

Judging from the reviews, the number of performances, and the literature on Tiresias, the ballet was neither a critical nor a commercial success. Perhaps the sexually charged choreography and risqué subject matter (glossed over in the programme notes) were too ahead of their time. After Fonteyn’s fiancé forbad her from performing the role again, her replacement Violetta Elvin took on the role, and when her she remarried, the same thing happened: her new husband banned her from dancing in further performances (Macaulay).

Clearly the erotic nature of the choreography was challenging in 1951. And this seems to have been the sticking point However, the iconoclastic choice of gender fluidity and sexual identity as subject matter, in addition to sexual pleasure, should in our opinion not be forgotten, as it is a testament to the daring nature of a choreographer who is perhaps too often associated with conventionality.

Concluding Thoughts

From this exploration of a small number of British ballets based on fairy tales and myth, it is clear that ballet is not entirely new to the concept of gender fluidity, and the more we dig into the characters, the more complex they become. Nonetheless, while attitudes towards gender, and the stereotypes associated with two strictly defined genders, are becoming more open in everyday life, ballet is only very slowly reflecting this cultural shift. Happily, this autumn two British companies have announced upcoming productions that will clearly feature gender-fluid characters: Northern Ballet’s Gentleman Jack, choreographed by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, and Scottish Ballet’s Mary Queen of Scots in choreography by Sophie Laplane.

As long ago as 2012 Gretchen Alterowitz urged her readers to “contemplate the possibility of multiple or varied genders having a place in the ballet world” (21). We would suggest that the example of Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s Broken Wings based on the icon Frida Kahlo shows us that ballet does in fact have the capacity to create worlds where a greater diversity of gender representation can be explored—a diversity more suited to our current world and more relevant to the global art form that ballet has become.

Next time on British Ballet Now and Then …

Autumn 2024 saw Noel Streatfeild’s 1936 novel Ballet Shoes adapted for the National Theatre. We investigate this new stage production, television adaptations, and the original book itself.

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

Alterowitz, Gretchen. “Contemporary Ballet: inhabiting the past while engaging the future”. Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies, no. 35, 2015, pp. 20-23.

Argyle, Michael. Bodily Communication. 2nd ed., Routledge, 1988.

“Ashton’s Cinderella – new Royal Ballet production”. BalletcoForum,https://www.balletcoforum.com/topic/26439-ashtons-cinderella-new-royal-ballet-production/. Accessed 1 Sept. 2024.

Balderas, Jessica Rodriguez. “Muxes, the third gender that challenges heteronormativity”. Institute of Development Studies, 3 Feb. 2020, https://alumni.ids.ac.uk/news/blogs-perspectives-provocations-initiatives/513/513-Muxes-the-third-gender-that-challenges-heteronormativity.

“The Ballerinas”. YouTube, uploaded by markie polo, 24 May 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sx2D40Wavwg&t=10586s.

Banes, Sally. Dancing Women: female bodies on the stage. Routledge, 1998.

Burgoon et al. Nonverbal communication. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2022.

Carli, Linda L. et al. “Nonverbal Behavior, Gender, and Influence”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 68, no. 6, 1995, pp. 1030–1041, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.6.1030.

“Carlotta Brianza as Carabosse with her entourage of rats in the opening scene of The Sleeping Princess 1921”. Victoria and Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/diaghilev-and-ballets-russes/more-diaghilev-and-film-industry.

“Cinders! 2023”. Scottish Ballet, https://scottishballet.co.uk/discover/our-repertoire/cinders/. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Christoudia, Melanie Trifona. “Carlotta Brianza”. International Dictionary of Ballet, edited by Martha Bremser, pp. 200-01

Dowler, Gerald. “The Royal Ballet – The Sleeping Beauty”. Classical Source, 3 Jan. 2017, www.classicalsource.com/concert/the-royal-ballet-the-sleeping-beauty-3/.

Elgin, Kathy. “Scottish Ballet’s Cinders! confirms Hampson is a savvy theatre-maker”. Bachtrack, 9 Jan. 2024 https://bachtrack.com/review-cinders-scottish-ballet-hampson-glasgow-edinburgh-december-january-2023-24.

Fracci, Carla. “The Ballerinas”. YouTube, uploaded by Markie polo, 24 May 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sx2D40Wavwg.

“Introducing Cinders with a Charming Twist to the Tale”. Scottish Ballet, 2013, scottishballet.co.uk/discover/news-and-articles/introducing-cinders/.

“‘It’s behind you! A look into the history of pantomime’”. University of York, 2010, www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/features/pantomime/.

Jennings, Luke. “The Sleeping Beauty/English National Ballet – review”. The Guardian, 9 Dec. 2012, www.theguardian.com/stage/2012/dec/09/sleeping-beauty-english-national-ballet.

Kavanagh, Julie. Secret Muses: the life of Frederick Ashton. Faber & Faber, 1996.

Knox, John. 1558. The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. Blackmask Online, 2022, http://public-library.uk/ebooks/35/36.pdf.

Liber, Vera. “The Sleeping Beauty”. British Theatre Guide, 2009, www.britishtheatreguide.info/reviews/RBsleepingbeauty-rev.

Macdonald, Nesta. Diaghilev Observed. Dance Horizons, 1975

Macaulay, Alastair. “Ashton and Balanchine: parallel lines”. NYU The Center for Ballet and the Arts, 2018, https://balletcenter.nyu.edu/lkl2018-script/

Mackrell, Judith. “Chase Johnsey’s unlikely success is a bold and beautiful victory for ballet”. The Guardian, 6 Feb. 2017, www.theguardian.com/stage/2017/feb/06/chase-johnsey-success-national-dance-awards.

—. “Girls Aloud”. The Guardian, 1 Dec. 2003, www.theguardian.com/stage/2003/dec/01/dance.

Mast, Marianne Schmid, and Sabine Sczesny. “Gender, Power, and Nonverbal Behavior”. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology, vol. 1, Jan. 2010, pp. 411-25, SpringerLink, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1465-1_20.

Plata, Gabriel. “Celebrating diversity: Meet Mexico’s Third Gender”. Inter-American Development Bank, 19 May 2019, https://www.iadb.org/en/story/celebrating-diversity-meet-mexicos-third-gender.

Parry, Jann. “Royal Ballet – The Sleeping Beauty – London”. DanceTabs, 14 Nov. 2019, https://dancetabs.com/2019/11/royal-ballet-the-sleeping-beauty-london-2/.

Pritchard, Jim. “The Royal Ballet exhibits Ashton’s Cinderella choreography in their Disneyfied new staging”. Seen and Heard International, 14 Apr. 2023, https://seenandheard-international.com/2023/04/the-royal-ballet-exhibits-ashtons-cinderella-choreography-in-their-disneyfied-new-staging/.

Reij, Dieuweke van. “Broken Wings: interview with designer Dieuweke van Reij”. English National Ballet, 20 Jan. 2019, www.ballet.org.uk/blog-detail/broken-wings-interview-designer-dieuweke-van-reij/

Rojo, Tamara. “Tamara Rojo South bank show 3”. YouTube, uploaded by Kabaiivansko2, 23 Apr. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfOoX16RLFM.

Titherington, Alan. “Tchaikovsky: The Sleeping Beauty (Royal Ballet – 2006)”. Myreviewer.com, 29 Sept. 2008, www.myreviewer.com/DVD/108291/Tchaikovsky-The-Sleeping-Beauty-Royal-Ballet-2006/108400/Review-by-Alan-Titherington.

Vaughan, David. Frederick Ashton and his Ballets. Rev. ed., Dance Books, 1999.

Wright, Peter. Wrights and Wrongs: my life in dance. Oberon, 2016.

Warner, Marina. “Witchiness”. London Review of Books, vol. 31, no. 16, 2009, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v31/n16/marina-warner/witchiness.

Watson, Paul. “On Fairy Tales and Witches”. The Lazarus Corporation, 6 Jan. 2015, https://www.lazaruscorporation.co.uk/blogs/artists-notebook/posts/on-fairy-tales-and-witches.

Windling, Terri. “Into the Wood, 9: Wild Men & Women”. Myth and Moor, 31 May 2013, https://windling.typepad.com/blog/2013/05/into-the-wood-8-wild-men-and-women.html.