I have always thought you would kill me. The very first time I saw you I had just met a priest at the door of my house. And tonight, as we were going out of Cordova, didn’t you see anything? A hare ran across the road between your horse’s feet. It is fate. (Mérimée 44)

Carmen is having a moment! This year marks the 150th anniversary of Georges Bizet’s celebrated opera, and new ballet adaptations have been created by Arielle Smith for San Francisco Ballet (April 2024) and by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa for Miami City Ballet (April 2025). As you may remember, both of these choreographers have featured in previous British Ballet Now & Then blog posts. In this post, however, we are focussing on Johan Inger’s Carmen, created in 2015 and now in the repertoire of English National Ballet.

Last year’s English National Ballet premiere was our first encounter with Inger’s Carmen. On first viewing we were mostly struck by the performances of the dancers. We had seen Minju Kang before with Northern Ballet, and of course we were hoping to see her in Kenneth Tindall’s Geisha, which was created on her, but we had no idea how feisty she was. Unsurprisingly, James Streeter received praise as Zuñiga, Don José’s commanding officer (from critics Teresa Guerreiro and Deborah Weiss, for instance), and Erik Woolhouse was sensational as Torero. Erik is our favourite ever Birbanto in Le Corsaire—another extrovert, audacious character, and we are still hoping to catch him as Hilarion in Akram Khan’s Giselle.

The set design by Estudio Dedos is another aspect of the work that we found very satisfying on first night: sets that create different spaces in a fluid and symbolic way capture our imagination (like the black cube in Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s Broken Wings, or the bookcases in Cathy Marston’s Victoria). As set designer Curt Allen explains, “the entire set arises out of one shape: an equilateral triangle”. Nine 3-sided prisms are moved around the stage space transporting the audience from mundane tobacco factory to glittering party venue to the foreboding mountains of Don José’s flight. Each side of each prism is different—mirror, concrete, black corrugated material—inviting parallels with the triangular relationship central to the dark tale: “three are a crowd, three stir up jealousy, three, alas, erupt into violence” (Allen).

Set, movement and music work together synergistically, like a Gesamtkunskwerk (total art work) that results in more than the sum of its parts. Rodion Schedrin’s 1967 orchestration of Georges Bizet’s opera (1875) has additional percussion, which adds a layer of energy, and maybe even suggests the violence that so interests Inger. But new music by Marc Àlvarez is integrated into this existing score to explore Don José’s inner world. What we found so impressive was the seamlessness of the result, a seamlessness that supports the recurring shifting between the tangible world and Don José’s inner torment.

The focus on Don José rather than on Carmen herself was something unexpected. However, given that Inger went back to Prosper Mérimeé’s 1845 novella, in which Don José tells the narrator his life story, after giving himself up and being condemned for Carmen’s murder, this focus was understandable. Yet despite Inger’s aim to explore the darkness of Don José’s psyche and expose the story’s domestic violence against women (qtd. in Compton), we found ourselves sympathising more with the tortured Don José than the deviant Carmen. It is Don José who both brings Act I to a close and then starts Act II with an unnerving running motif, and while he is clearly running from the authorities after killing Zuñiga, the vicious undercurrents of the score speak of a man desperately attempting to escape from himself and his own obsession.

We wondered whether our sympathy was also connected to the casting. Rentaro Nakaaki, a young dancer who joined the Company in 2018 and almost still looks like a teenager, has an air of naivety about him. Critic Jenny Gilbert commented on the effect of his “loose-limbed dancing” on her sympathetic reaction to the character, stating that he “was a joy to watch throughout”. But on subsequent viewings we still found ourselves sympathising with this character. Inger himself aims to be “honest” and “very human” in his choreography “to get to the people beneath” (qtd. in Compton), and his choreography for Don José accentuates the character’s struggles, with ample solo time for dancers to explore nuances in interpretation. For example, Aitor Arrieta seemed to highlight the character’s concern for his image and his desire to “do the right thing”. There was an awareness of and anxiety about the incongruities in his behaviour, so the tension was driven by his desperate struggle to resist his urges and hang on to his sense of self. In contrast, Fernando Carratalá Coloma seemed to succumb to the inevitable with less resistance, and his desperation was more an expression of his grief at unrequited desire, and his perceived lack of agency in the situation.

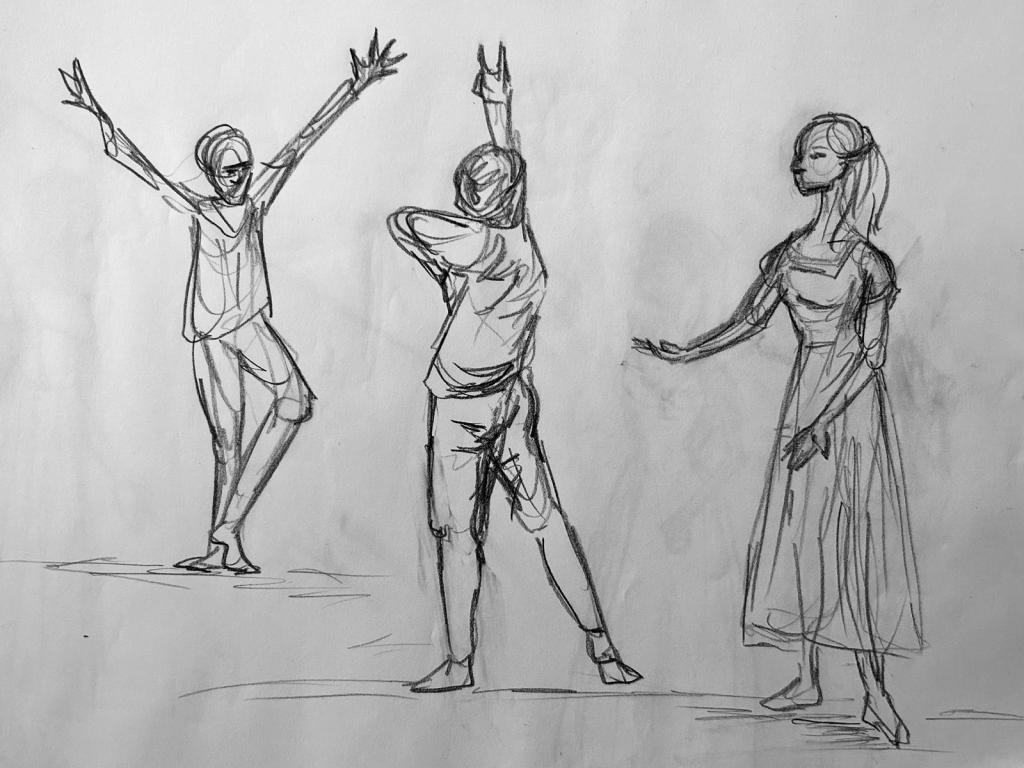

Something we struggled with was what we saw as something of a disconnect between Inger’s description of Carmen as a “feminist” and the way Carmen, and indeed the other Cigarreras, were represented on the stage. When the women enter the first time and dance in unison, they appear to take charge of the space as powerful determinants of their own destiny: most of all we remember the motif of the low wide fourth position, their arms in attitude greque and their gaze directed firstly to the audience and then on repeat to Zuñiga. But they are also brazen and flirt outrageously, as well as fighting amongst themselves in a way that could be perceived as disempowering. We found it difficult not to interpret the way they strut their stuff as inviting the male gaze rather than challenging it and wondered whether a female choreographer would present them differently. On the other hand, Carmen’s refusal to play by societal rules that demand a certain behaviour from her afford her a strength of character that Don José, so bound by those rules, lacks.

We always enjoy ambiguity in a work, so we were intrigued by The Boy, who is in fact performed by a female dancer. Significantly, they frame the whole narrative, perhaps symbolising youth and innocence that ultimately breaks down, but possibly also representing an integral feature of Don José’s character, even a stereotypically feminine side. Here we are thinking in particular of his longing for domesticity, and the reticence of his public demeanour, particularly in contrast to the other male protagonists, and in fact to Carmen and the other Cigarreras. To us this reticence was really noticeable in Carratalá Coloma’s posture on his first entrance, and in the way that Nakaaki was at times a palpable presence on stage, but without being central to the action—more like an onlooker.

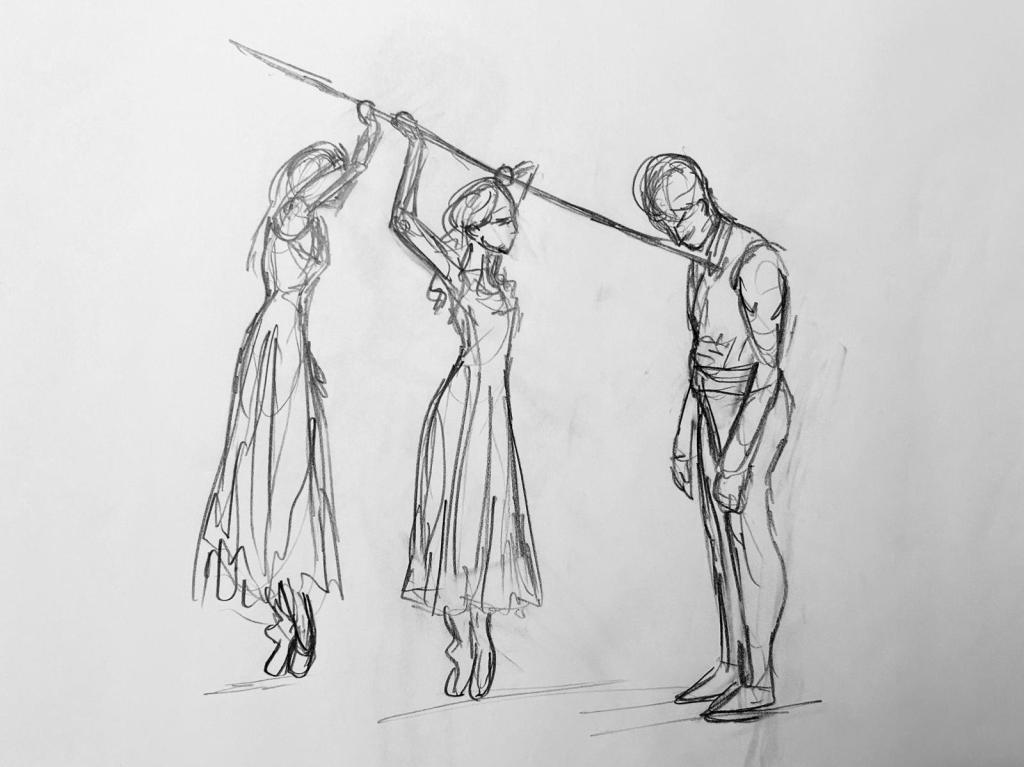

One of the scenes that stood out was a trio with Don José, Carmen and The Boy that represents Don José’s vision of domestic bliss in the middle of a vicious fight with Carmen. It was noticeable that this pas de trois, which struck us as rather humorous, even ironic, was choreographed to the music that is given to the central pas de deux for Carmen and Don José in Roland’s Petit’s 1949 choreography for himself and Zizi Jeanmaire.

Other ambiguous characters are The Shadows, dressed in black, who seemed to us to represent fate—fate that Carmen is all too aware of in Mérimée’s novella. The presence of fate manifests itself in the structure of Inger’s piece, beginning and ending as it does with The Boy and one of The Shadows. As the work progresses The Shadows multiply and visibly draw it to its climax. It is as if they are the driver of Don José’s obsession, and as if Carmen’s death at his hand were preordained by some inexorable force—maybe even societal forces that drive the way we construct gender and therefore perceive man- and womanhood.

It’s noticeable that although we see Carmen philandering with her other lovers, the only duet she performs is with Don José. And the mirroring in the choreography clearly communicates a connection between them. But despite this, Carmen’s behaviour demonstrates that she is in no way tempted to accept Don José as a permanent fixture in her life. And then again we wondered whether this connection were simply a figment of Don José’s imagination, or wishful thinking on his part.

We are very aware that we have focused a lot of attention on Don José in this post, but that, we feel, is a reflection of Inger’s work. Carmen’s character is clear from her actions: she is energetic, fiery and independent, but also violent, rude and unfeeling. We wondered whether, if she had more solo material, we would see more depth in her character.

We found Matthew Paluch’s perspective helpful. He says:

Femicide is a deeply uncomfortable, pressingly current topic, but it doesn’t make the premise of Carmen any easier to swallow. Inger’s Carmen is very difficult to like, as her raison d’être seems to have zero consideration for others, so the audience is presented with questions as to how we approach her demise. It’s a very conflicting tactic.

We relish the wealth of possible meanings engendered by Inger’s ballet, and we appreciate the perplexing nature of the work. To us it seems to reflect Carmen’s words to Don José before he murders her:

You mean to kill me, I see that well. It is fate. But you’ll never make me give in … You are my rom [husband], and you have the right to kill your romi, but Carmen will always be free. (Mérimée 46)

Nonetheless, this is a work by a male choreographer, commissioned by a male artistic director (José Carlos Martínez), and based on a novella by a male writer, made famous by a male composer. The two recent adaptations that we mentioned at the start of this post have been created by female choreographers, and commissioned by female artistic directors (Tamara Rojo and Lourdes Lopez, respectively). Both choreographers have noted the emphasis on Don José in the original story and expressed their desire to present a work more focussed on Carmen herself:

The very basic theme, that I think is powerful, is it’s a piece about a woman … And that, for me, on the very basic level, was my job, was to make this piece Carmen’s story; otherwise we shouldn’t call it Carmen. (Smith 07:15-07:34)

I wanted my ballet to be more about a strong woman that yearns to be independent, that wants a job and that wants to go higher in the social rankings. (Ochoa 0:32-01:46)

Crucial for us is that both Carmens are involved in business: Smith’s heroine takes over the family restaurant, while Ochoa’s protagonist develops her career from card dealer to poker queen. This gives them a different kind of agency to Mérimeé’s creation: feisty and rebellious though she may be, the original Carmen does not use her wit and intelligence to better her lot in life or resist her fate, but accepts that her community can demand her life if she refuses to conform to its mores.

Carmen is clearly a seductive subject matter for artistic creators, but with its themes of violence and cultural stereotyping, an increasingly difficult one. We welcome further balletic investigations into Carmen’s character, but for starters we would love to see the interpretations of Arielle Smith and Annabelle Lopez Ochoa on a UK stage.

With thanks to Jodie Nunn for her contribution to the writing of this post

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

Allen, Curt. “Setting the Scene.” Programme for Johan Inger’s Carmen at Sadlers Wells Theatre, English National Ballet, London, 2024.

Crompton, Sarah. “Getting under the skin of Carmen: interview with Johan Inger.” Programme for Johan Inger’s Carmen at Sadlers Wells Theatre, English National Ballet, London, 2024.

Gilbert, Jenny. “Carmen, English National Ballet review”. The Arts Desk, 3 Apr. 2024, https://theartsdesk.com/dance/carmen-english-national-ballet-review-lots-energy-even-violence-nothing-new-say.

Guerreiro, Teresa. “English National Ballet, Carmen Review”. Culture Whisper, 28 Mar. 2024, https://www.culturewhisper.com/r/dance/english_national_ballet_carmen_sadlers_wells/17825.

Mérimée, Prosper. Carmen. Alpha Editions, 2021.

Ochoa, Annabelle Lopez. “Carmen: In Conversation”. YouTube, uploaded by Miami City Ballet, April 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vXgM9B8XdM.

Paluch, Matthew. “Review: English National Ballet – Carmen”. Broadway World, 28 Mar. 2024, https://www.broadwayworld.com/westend/article/Review-ENGLISH-NATIONAL-BALLET-CARMEN-Sadlers-Wells-20240328.

Smith, Arielle. “‘She never felt like the protagonist of her own story’”. YouTube, uploaded by San Francisco Ballet, 16 Nov. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfdCAk7FbOM.

Weiss, Deborah. “English National Ballet: Johan Inger’s Carmen is chillingly topical”. Backtrack, 28 Mar. 2024, https://bachtrack.com/review-carmen-johan-inger-english-national-ballet-sadlers-wells-march-2024.