When Ninette de Valois’ ballerina Alicia Markova left the Vic-Wells (now Royal) Ballet in 1935, initially there was no single dancer capable of taking her place, due to the extent of her repertoire and skills. Instead, Markova’s roles were divided amongst a group of dancers, including Margot Fonteyn, who became the most celebrated of the group by far. The other dancers were Elizabeth Miller and Pamela May, already with the Company, plus two new recruits, June Brae and Mary Honer. This last dancer, Mary Honer, is the focus of this British Ballet Now & Then post. And the reason we have chosen Mary is that Elizabeth Honer, CEO of the Royal Academy of Dance since January this year, is related to her: Mary was in fact second cousin to Elizabeth Honer’s father, and a great influence on Elizabeth’s passion for ballet.

Not a great deal has been written about Mary, so it has been quite a journey finding out sufficient information about her to fill a blog post, rather like following a trail of breadcrumbs. Still, rifling through books, magazines, journals and programmes, finding bits and pieces of information from primary as well as secondary sources, and fitting them all together like a jigsaw makes us feel like detectives uncovering a mystery, and we have found it quite exhilarating.

Something that set Mary apart from her colleagues was her professional experience in musical comedy and revue. This was of course not unusual at the time—it’s easy to forget how closely intertwined the establishment of ballet in Britain was with the music hall. Adeline Genée, Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Lydia Lopokova, Phyllis Bedells and Ninette de Valois all danced in London music halls, and Frederick Ashton choreographed for musicals and revues. In fact the first role that Ashton created for Mary was not in the context of the Vic-Wells Ballet: we were interested to discover that in 1933 he had choreographed “an exquisite ballet” for the musical Gay Hussar “with the dainty Miss Honer” (The Stage qtd. in Vaughan 91).

Of the dancers who took over Markova’s roles, the two performers who by all accounts were the most technically accomplished were Elizabeth Miller and Mary. At this particular time in the development of British ballet technical proficiency must have seemed almost a matter of life and death. Reminiscing on the period, photographer Gordon Anthony (brother of Ninette de Valois) comments on the Vic-Wells dancers: “Its dancers then were rich in talent but comparatively weak in technical accomplishment” (88). Now that British ballet is so securely established with major companies, such as the Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, Northern Ballet and Scottish Ballet, as well as smaller troupes, including London City Ballet and Ballet Black, it is difficult to imagine that in the 1920s and ’30s ballet was perceived predominantly as a foreign, and more particularly Russian, art form. For de Valois dancers with secure technical ability were crucial to her plans for the repertoire: a combination of 19th and early 20th century “classics” and new works that would serve as a secure foundation for the development of her Company and the creation of a distinct British style.

In Mary Honer de Valois certainly found herself a dancer who could rise to any technical challenge. Here are just a few examples of comments about Mary’s technique:

“She brought with her a virtuoso technique hitherto unseen at Sadler’s Wells (Manchester 98)

“very strong technique” (Clarke 152)

“a delicious soubrette with a formidably strong technique” (Walker 23)

“brilliant technician” (Vaughan 123)

“a virtuoso dancer” with “technical strength” (Morris 104)

Most enthusiastically and evocatively, Anthony described her as “a pyrotechnical magician of those days, tossing off pirouettes and fouettés as if they were pink gins at a cocktail party” (88).

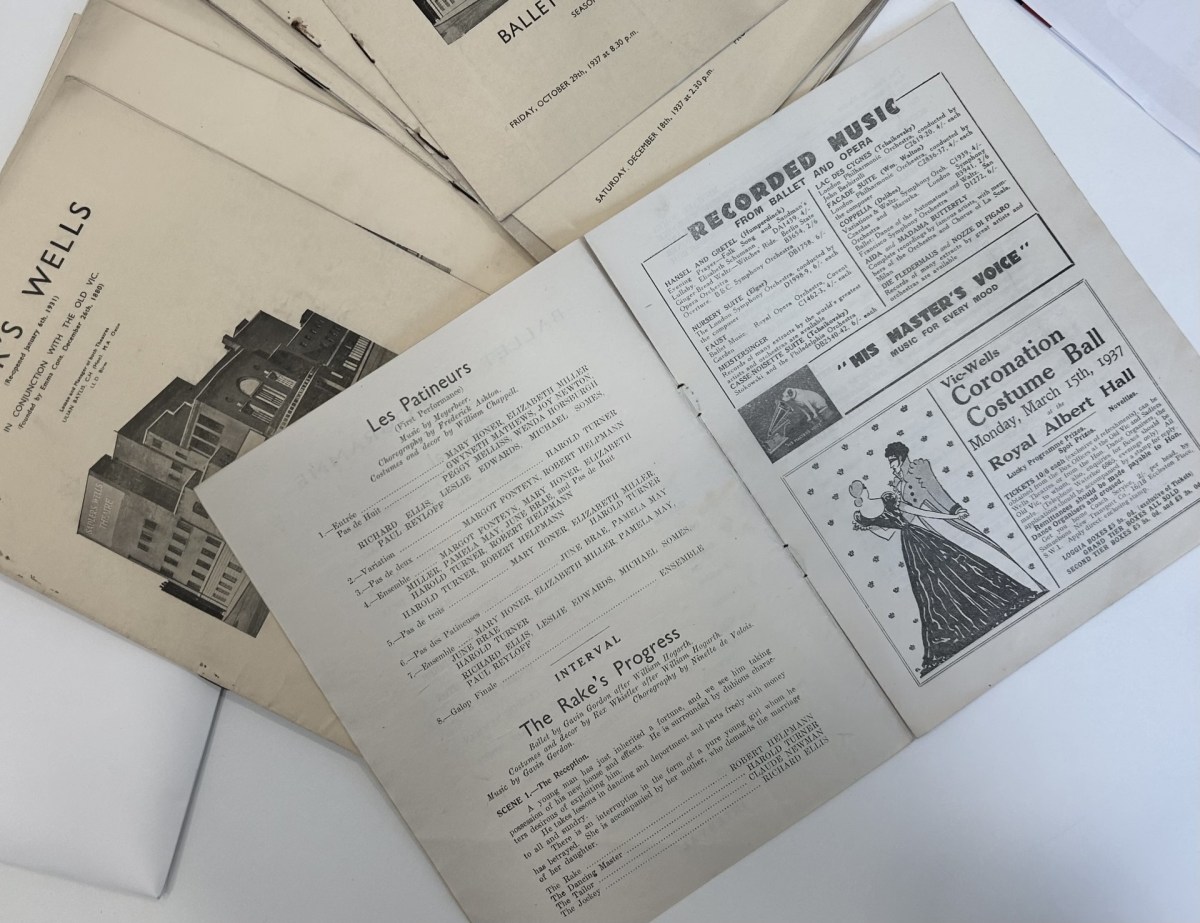

Mary’s technical prowess is suggested too by her casting as Odile to Margot Fonteyn’s Odette in Swan Lake (Le Lac des Cignes as it was known in those days) (Bland 279). According to Fonteyn’s biographer Meredith Daneman, it was in the event the more experienced Ruth French who performed the role (97). Ashton’s biographer and esteemed dance historian David Vaughan however states that French and Honer shared the performances of Odile until the autumn of 1937 when Fonteyn was considered sufficiently strong in technique and stamina to perform the dual role (158). Following some additional research we were very excited to discover a programme, probably from early 1937, listing Fonteyn as Odette, Honer as Odile, and signed by both ballerinas (“Swan Lake, The Vic-Wells Ballet- 1937”): incontrovertible evidence of Honer’s performance as Odile to Fonteyn’s Odette. Interestingly, this casting is also recorded in Alexander Bland’s statistics in the appendices of The Royal Ballet: the first 50 years (279), but within the text only Ruth French is acknowledged as Fonteyn’s Swan Lake counterpart (46). The vagaries of research!

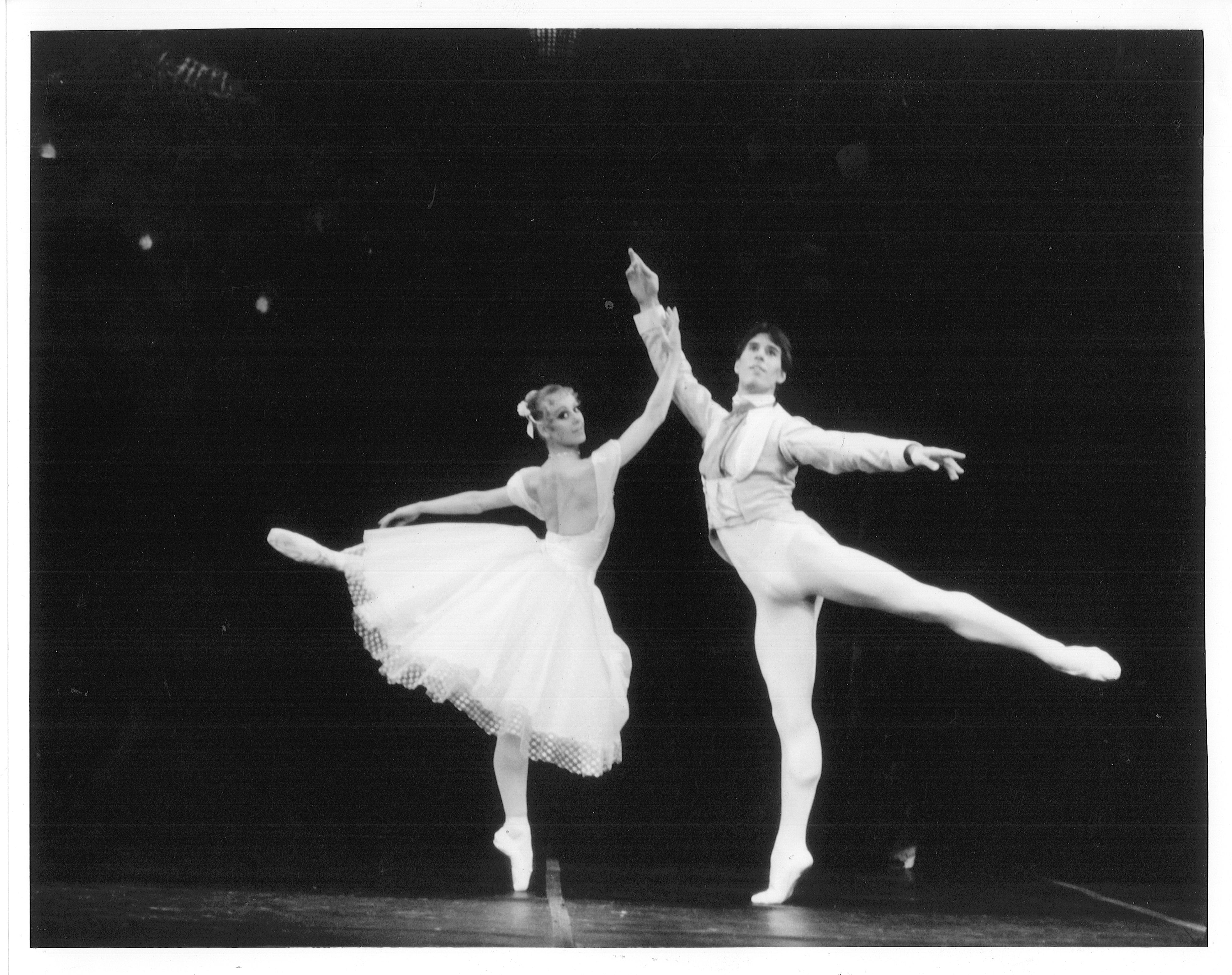

In the same year Ashton created Les Patineurs. According to Ashton’s biographer Julie Kavanagh, his “main aim was to reveal the virtuosity of the burgeoning English ballet” (209). While Fonteyn danced the central pas de deux with Robert Helpmann, it was for Elizabeth Miller and Mary Honer that he created the “Blue Girls” with their effervescent and highly challenging choreography. Even Daneman states that Fonteyn and Helpmann’s “thunder was easily stolen by the virtuoso Blue pas de trois” performed by Miller, Honer and Harold Turner (111).

Although there are no existing recordings of the original Les Patineurs cast, we have watched videos from a variety of companies (American Ballet Theatre, Joffrey Ballet, London City Ballet, Royal Ballet), and from this feel that we have gained a sense of Honer’s technical capabilities. In the pas de trois, the continuous terre à terre work combined with adagio movements requires great stamina as well as precision. We are thinking here of repeating motifs such as relevé lent devant through passé into arabesque while executing temps levés, or demi grand rond de jambe sauté en dehors continuing round to arabesque while doing a series of temps levé en tournant, the whole motif accompanied by a huge port de bras. There were also challenges in pointe work, such as turning hops sur pointe with the working leg in attitude devant. Given what we know about the casting of Honer as Odile, it is perhaps unsurprising that her role climaxes in a series of fouettés, but with the added complexity of integrating some pirouettes à la seconde and taking the arms to fourth position on every fourth turn. And in case we are tempted to assume that in the latter part of the 20th century dancers would have made the choreography more complicated to suit advances in technique, according to Kavanagh, towards the end of his life, Ashton would complain that “it was so much more complicated then than it has become” (209). This also resonates with Bland’s assertion that the “spinning Girls in Blue, Mary Honer and Elizabeth Miller, were to set a challenge for their many later replacements” (49).

While we have emphasised Honer’s technical capabilities because of their significance in the development of British ballet during the 1930s, we in no way wish to pigeon-hole her. The range of Mary’s repertoire implies that she was in fact very versatile. Another role which Ashton created for her was the Bride in his A Wedding Bouquet, which premiered two months after Les Patineurs. Here Mary danced a parody of a classical pas de deux with Helpmann. Photographs by Gordon Anthony depict Mary posing in elegant positions while Helpmann partners her awkwardly by for example facing the wrong direction, appearing as if he is dragging her along behind him, or balancing her in a swoon on his knee with his arm hooked over her waist (Vaughan 150-51). Mary Clarke, dance historian and editor of the Dancing Times for forty-five years, provides a wonderfully vivid description of Mary Honer as the Bride: “She simpered and blushed and giggled her way through the ballet” (130). Clearly the effectiveness of Mary’s performance in the role was displayed through the combination of a keen comedic talent and the physical control required to end “upside down and back to front in most of the pas de deux … without looking ruffled by the experience” (Morris 104). In fact Kavanagh asserts that Mary was so hilarious as the Bride that Helpmann felt upstaged by her (212). Another Ashton ballet that capitalised on Mary’s comedic gifts was The Wise Virgins (1940), based on the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins from Saint Matthew’s Gospel. Writing in 1946, ballet critic Audrey Williamson declared that as the leader of the Foolish Virgins, Mary “plumbed depths of disarming silliness no one has ever achieved since” (75).

The role that seems to have been central to Honer’s classical repertoire was Swanilda in Coppélia (Saint-Léon, 1870; Cecchetti, 1894): a role requiring both comedic talent and technical virtuosity. With its two acts, the Vic-Wells’ 1933 production of Coppélia was the first multi-act 19th century “classic” staged by de Valois, and as such a crucial work in the establishment of ballet as an art form in this country. In 1940 Honer was chosen as first cast for the first three-act production of Coppélia in this country, making her the first English Swanilda in a full-length production, a performance for which she received a well deserved ovation, according to Richardson (464), and garnered much critical acclaim (Fisher 14; Manchester 99). Mary gave the role a “saucer-eyed wistfulness and mischief and a steel-pointed technique of glittering virtuosity”, wrote Williamson (120), intimating that the ballerina not only dazzled the audience with her rendition of the choreography, but also excelled in creating a warm, funny and captivating character.

In complete contrast to Swanilda is the Betrayed Girl in de Valois’ The Rake’s Progress, based on William Hogarth’s set of paintings. Although she finds herself pregnant by the Rake, the Betrayed Girl uses her savings to pay off his debts, and later, once his fortunes have deteriorated, visits him in the prison where he dies. This role differs from Mary’s most celebrated roles not only in character, but in style and technique. The Girl’s best known dance is probably her solo near the prison gate, which is also a personal favourite of ours and has been described as de Valois’ most lyrical piece of choreography (Williamson 62). The poignant dance shows her embroidering with motifs of developpés, lunges and relevés in attitude devant accompanied by port de bras representing her pulling thread through the fabric on her embroidery hoop. After this she puts the hoop down and gives into her distress through a series of weeping, reaching and pleading motifs. More motifs show her anxiously looking from side to side as she performs stuttering glissades piqués sur pointe. With its repeated motifs and cyclical structure the solo conveys to us a sense of time passing, suggesting the Girl’s loyalty and steadfastness, as well as her sorrow. The dance is understated, with emotion and character communicated through the combination of danse d’école and contained, stylised gesture.

Given what we have learnt about Mary’s virtuosic style, the Betrayed Girl seems an unlikely candidate as a highlight in her repertoire. Yet we have found a number of sources that draw attention to her interpretation of the role. Williamson remarked on the “true eloquence” of her hands in the embroidery solo, and the “wounded and wistful loyalty that was deeply touching” in the final scene (62). Her performance is described in her Dancing Times obituary as “wholly credible” in its “simplicity” (“Miss Mary Honer”), and Gordon Anthony even declared that she surpassed both Alicia Markova and Margot Fonteyn in the role (89), an opinion clearly shared by Williamson for whom Mary represented the “the criterion for this part” (62). These descriptions and appreciations of Mary in this role made us very happy, as they suggest that Mary was a far more versatile dancer than it seemed in the beginning stages of our research.

The Rake’s Progress was one of the ballets broadcast on the BBC before the service was shut down for the duration of World War II. It was such serendipity that the advent of television coincided with the fledgling years of British ballet. On 2nd November 1936 the BBC opened the world’s first regular high-definition television service. Three days later Ballet Rambert became the first British ballet company to be broadcast, swiftly followed by the Vic-Wells on November 11th (Davis 363). The BBC became an important patron of the arts, not only broadcasting but also commissioning concert music, plays, and yes, ballets, most notably by another significant British ballet choreographer, Antony Tudor (BBC Story: 1930s; Davis 302-03).

Between 1936 and the outbreak of World War II on 1st September 1939, the Vic-Wells Ballet regularly appeared on the BBC, and Mary, of course, made a significant contribution to these broadcasts. In addition to dancing the Betrayed Girl on television, Mary performed classical roles, including Princess Florine and the Sugar Plum Fairy, and 20th century works, most notably the two Ashton roles that had been created for her in Les Patineurs and A Wedding Bouquet, and her photograph appeared in the Radio Times Television Supplement in March 1937 in the Grand pas de deux from The Nutcracker (or Casse-Noisette as it was known at that time) (“Pre-war Television” 3). She also danced a role for which she received particular praise from both Phillip Richardson, editor of The Dancing Times, who declared her to be “at her best as Papillon” in Fokine’s Carnaval (138), and Gordon Anthony, who remembered the excitement of her “speed, lightness and precision” (89).

What we found more interesting, however, was that from the autumn of 1937 a small number of prominent dancers were given the opportunity to each curate a 10-minute programme highlighting their own individuality. Dancers included Alicia Markova, Pamela May, and unsurprisingly, Mary Honer. In 1938 Mary performed two such recitals. Some dances were evidently arranged specifically for the occasion, but for existing repertoire, in addition to the Sugar Plum Fairy variation and the ballerina solo from Ashton’s Les Rendezvous, Mary chose Odette’s solo from Act II of Swan Lake (Davis 284). To us this seems like a very deliberate choice that displayed Mary’s versatility rather than simply emphasising those qualities for which she was best known.

While television seems to us to have been an ideal medium to promote ballet, journalist John swift, who under the pseudonym “The Scanner” had a column in the television section of Radio Times, emphasised rather the importance of ballet for television, stating “One thing is clear: that ballet has established itself firmly as an important part of the more serious side of television programmes” (“Pre-war Television” 22).

Unexpectedly, in the course of our research we came across a repeated anecdote that gives us an impression of Mary’s character, her attitude to her work and to her colleagues. Several sources describe a performance of The Sleeping Princess (later named The Sleeping Beauty) where Pamela May, who was dancing the Lilac Fairy, unfortunately injured herself during the Prologue. That evening Mary was performing her usual roles—the Breadcrumb Fairy (known as the Violet Fairy in that production) and Princess Florine (Bluebird Pas de deux). Despite never having rehearsed the Lilac Fairy’s choreography, Mary’s reaction to her colleague’s unfortunate accident was to complete the Lilac Fairy performance in Pamela May’s stead as well as dancing her own roles. It was only in the Apotheosis that an additional dancer (Julia Farron) was needed to cover the last section of the Lilac Fairy’s role (Anthony 89; Clarke 166; Leith xii; Manchester 99). Critic P. W. Manchester showed her admiration for Mary’s dedication and intrepidness in the following words: “She can have known the part only because she had assiduously watched rehearsals when she might easily have chosen to take the time off”.

One further anecdote tells us of Mary’s commitment to the Company, and of her sense of fun. In 1950, at the Sadler’s Wells 21st anniversary gala, Mary reprised her role of the Bride in A Wedding Bouquet, despite having left the Company over seven years earlier. Evidently her performance showed an undiminished vitality: she looked “radiant and unchanged” (Clarke 253) “with all her old skill and charm” (“Miss Mary Honer”).

When Mary died in 1965, the Dancing Times paid tribute to her contribution to the development of British ballet in its formative years:

Virtuosity, in those days, was a rare ingredient in our national ballet and Mary Honer’s dancing set a standard and provided an example … She was proud of the role she played in the development of our national ballet and rightly so for her contribution was great. Technical standards have risen fantastically since her day—but the choreography written for her in Les Patineurs still taxes our strongest dancers. (“Miss Mary Honer”)

This obituary concludes with the uncompromising words “Her place in ballet history is safe”. But of course this brings us to the perplexing question of why the name of Mary Honer is not a more familiar one in British ballet history. For that burning question we have a few suggestions.

We have wondered whether, despite Markova’s status, experience and skill, de Valois was not altogether unhappy at her departure. De Valois’ aim was to develop dancers nurtured within her Company (Quinton), but although Markova was only 22 when she joined the Vic-Wells ballet, she had already danced with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes for four years, been ballerina of the Camargo Society, and was dancing with Marie Rambert’s company. Similarly, when Mary arrived, she was, as Gordon Anthony put it “already a premiere danseuse of some note” (88). Fonteyn, on the other hand, was only fourteen years old when she joined de Valois’ school and debuted with the Company (Daneman 62). This circumstance allowed Fonteyn to develop into a truly “home-grown ballerina” (Hall 259).

The critics and dance writers of the 1930s and ’40s, such as Arnold Haskell, Lawrence Gowing, P. W. Manchester, Fernau Hall, and Ninette de Valois herself, were intent on ballet becoming integral to British cultural life, but also on ensuring that it would be considered a serious art form. Perhaps as a way of educating audiences, they seemed keen to categorise dancers as particular types. Apart from being labelled as a technical and virtuosic dancer, the descriptor most often applied to Mary was “soubrette”, a term both used at the time and reflected in later writings (Clarke 152; Manchester 99; Walker 23). As we have noted, the strength and ease of Mary’s technique was crucial at this time in the development of ballet performance and culture, something that is highlighted in favourable comparisons with Russian dancers (Vaughan 148; Manchester 99). Manchester expresses this point in no uncertain terms: “Her fouettés have the freedom and sweep of which previously only the Russians have held the secret”.

Yet, in our opinion, such labels as “soubrette” and “technical” can be rather limiting, and as you will have noted, from our research we have gained the impression that Mary was a rather versatile dancer. A number of writers referred to certain “mannerisms” (Fisher 14; Gowing 494; Manchester 98) that were presumed to be a result of Mary’s work in revues and musicals and deemed unsuitable for performing in a serious ballet company. We noted however that critics regularly commented on dancers’ improvements in technique and expression, and indeed some critics remarked on developments in Mary’s performances. The statements that Mary had “widened her mimetic range to an astonishing extent” (Manchester 98) and “acquired a true classical style” (“Miss Mary Honer” 477) suggest to us that she had not only “shed the mannerisms” (Fisher 14), but that over time her dancing developed in both expressivity and in refinement of style. Further, we do wonder whether drawing attention to this aspect of Mary’s performances was the result of some degree of snobbishness on the part of critics who were so eager for ballet to be perceived as a serious art form, and consequently wished to distance ballet from its ties with the music hall. Perhaps there was even a sense of resentment surrounding a dancer from what they considered a more lowly art form being able to out-fouetté, as it were, dancers with only ballet experience. We did also find it curious that even within the same article descriptions of Mary’s performance style could be contradictory. For example, while Gowing criticised Mary’s “mannered” hand movements, on the same page he describes her Princess Florine as “possibly the most perfect single piece of dancing seen on the Sadler’s Wells stage this season” (494). So to return to our main point, we believe that this association with revue and musicals could be another reason why so little has been written about a dancer who must have been influential at the time: we cannot imagine that her colleagues were not inspired to emulate her technique.

Although they may seem insignificant, there are two discoveries which brought home to us Mary’s importance to the Vic-Wells Company and to the flowering of ballet in this country. The first was Bland’s description of the way de Valois’ company had developed by 1939, numbering up to forty dancers “with at least the mandatory four principals – Fonteyn, Helpmann, Honer and Turner” (57). The phrase “mandatory four principals”, followed by an alphabetical list, implies not only equal ranking amongst the four dancers, but also that they were absolutely crucial to the Company. The second discovery was a cartoon from the same year by Charles Reading, stage designer at Sadler’s Wells Theatre (131). It depicts four “Sadler’s Wells Personalities”: Constant Lambert, Ninette de Valois, Robert Helpmann and Mary Honer. And who bothers to produce a cartoon of someone insignificant?

Mary left de Valois’ company at the end of 1942. While she continued her involvement in ballet by occasionally dancing with the Ballet Guild, becoming a member of The Royal Academy of Dancing (RAD) Major Examinations’ Committee and running a dance school, this means she was not involved in the post-war events that catapulted the Sadler’s Wells Ballet to international fame: the legendary re-opening of the Royal Opera House in 1946, and the triumphant first visit to New York in the autumn of 1949. Both of those events were led by performances of The Sleeping Beauty, which was to become the Company’s signature ballet. Both first nights were led by Margot Fonteyn as Aurora: the part that was to become her signature role. By the 1950s Fonteyn had become an international celebrity, and books about her by Cyril Beaumont (1948), Cecil Beaton (1951), Hugh Fisher (1954), James Monahan (1957), and Elizabeth Frank (1958) further thrust her into the limelight, contributing to the mythological figure she still is today.

Concluding thoughts

Mary Honer was distinctive in a number of ways: she demonstrated an unprecedented brilliance of technique that rivalled the Russian dancers of the time; she inspired Ashton in his choreography when the British ballet repertoire was starting to be developed; she could dance all the 19th century classics that de Valois introduced into the repertory and promoted to give British ballet more gravitas as a serious art form based on a strong tradition; and Mary was adaptable and versatile with a great work ethic and spirit of collegiality. The range of Mary’s roles can be seen in the table below.

Nonetheless, despite the confident words of the Dancing Times, Mary’s place in British ballet history has not been as safe as predicted. We hope therefore that this post goes some way to restoring her to her rightful place as a pioneer of British ballet.

We would like to thank the Library staff at the Royal Academy of Dance, particularly the wonderful archivist and dear friend Eleanor Fitzpatrick. Thanks also to our research assistant Jodie Nunn who, with her usual enthusiastic and energetic spirit, has helped with trawling through programmes from the archives, and Dancing Times editions from 1935 to 1943. And finally, a thank you to Madeleine of Madeleine’s Stage for permission to use the image of her signed Lac des Cygnes programme.

Mary Honer’s Roles with the Vic-Wells Ballet

| Work/ Production | Role |

| Façade (Ashton, 1931) New production (1935) † | **Scotch Rhapsody Tarantella and Finale (1939) |

| Les Sylphides (Fokine, 1909) (staged by Markova, 1932) | Mazurka (1936) Valse (1938) |

| Coppélia (Saint-Léon, 1870; Petipa/Cecchetti, 1894) Coppélia Acts I & II (staged by Sergeyev, 1933) | Swanilda (1938) |

| Le Carnaval (Fokine, 1910) † (staged 1933) | Papillon (1935) |

| The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890) “The Bluebird Pas de deux” (staged 1933) | The Enchanted Princess (1935) |

| The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890) “Aurora Pas de deux” (staged 1933) | Aurora (1936) |

| Les Rendezvous (Ashton, 1933) | Ballerina role (1937) |

| Giselle (Coralli / Perrot, 1841) (staged by Sergueyev, 1934) | Peasant Pas de deux (1939) |

| The Nutcracker (Ivanov, 1892) Casse-Noisette † (staged by Sergeyev, 1934) | Sugar Plum Fairy (1935) |

| Swan Lake (Petipa/Ivanov, 1895) Le Lac des Cygnes (staged by Sergeyev, 1934) [Sometimes Act II, or III, was performed alone as part of a mixed bill.] | Act I Pas de trois (1935) Odile (1936) Odette/Odile (1937) Odette (1938) † Odette Act II solo † Odile Act III solo |

| The Rake’s Progress (de Valois, 1935) † | The Betrayed Girl (1936) |

| Le Baiser de la Fée (Ashton, 1935) | * Spirit |

| The Gods go a’Begging (de Valois, 1936) | *Serving Maid |

| Apparitions (Ashton, 1936) | |

| Nocturne (Ashton, 1936) † | |

| Prometheus (de Valois, 1936) | *Prometheus’ Wife |

| Les Patineurs (Ashton, 1937) † | *Blue Girl |

| A Wedding Bouquet (Ashton, 1937) † | *The Bride |

| Horoscope (Ashton, 1938) | *Follower of Leo |

| The Sleeping Beauty (Petipa, 1890) The Sleeping Princess (staged by Sergeyev, 1939) † | **Breadcrumb (Violet) Fairy **Princess Florine (Bluebird pas de deux) Diamond Fairy (1940) Lilac Fairy (unplanned) |

| Cupid and Psyche (Ashton, 1939) | * Minerva |

| Coppélia Acts I-III (staged by Sergeyev, 1940) | **Swanilda |

| The Wise Virgins (Ashton, 1940) | *Leader of the Foolish Virgins |

| The Prospect Before Us (de Valois, 1940) | *Street Dancer |

| Façade (Ashton, 1931) New production (1940) | **Maiden (Country Dance) |

| The Wanderer (Ashton, 1941) | * Allegro, Presto, Finale |

| Orpheus and Eurydice (de Valois, 1941) | *Leader of the Furies |

* created role

** production first cast

† televised performance

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

“American Ballet Theatre Les Patineurs (complete)”. YouTube, uploaded by David Coll, 6 Sept. 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSdROtoWdJk.

Anthony, Gordon. “Pioneers of the Royal Ballet: Mary Honer”. Dancing Times, vol. LXI, no.722, 1970, pp. 88-89.

“The BBC Story Factsheets: 1930s”. BBC, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/timelines/.

Bland, Alexander. The Royal Ballet: the first 50 years. Threshold Books, 1981.

Clarke, Mary. The Sadler’s Wells Ballet: a history and appreciation. A & C Black, 1955.

Daneman, Meredith. Margot Fonteyn. Viking, 2004.

Davis, Janet Rowson. “Ballet on British Television”. Dance Chronicle, vol. 5, no. 3, 1983, pp.245-304.

De Valois, Ninette. Invitation to the Ballet. John Lane The Bodley Head, 1937.

Fisher, Hugh. Ballerinas of Sadlers Wells. Adam and Charles Black, 1954.

Hall, Fernau. Modern English Ballet: an interpretation. Andrew Melrose, 1949.

Haskell, Arnold. Prelude to Ballet: a guide to appreciation. Thomas Nelson, 1936.

Gowing, Lawrence. “English Dancers in English Ballet”. Dancing Times, New Series, no. 316, 1937, pp. 489-94.

Kavanagh, Julie. Secret Muses: the life of Frederick Ashton. Faber and Faber, 1996.

Leith, Eveleigh. Introduction. The Sadler’s Wells Ballet: camera studies by Gordon Anthony, 1942.

Manchester, P. W. Vic-Wells: a ballet in progress. Victor Gollancz, 1946.

“Miss Mary Honer”. Dancing Times, vol. LV, no. 657, 1965, p. 477.

Morris, Geraldine. Frederick Ashton’s Ballets. 2nd ed., Oxford UP, 2024.

Noble, Peter, editor. British Ballet. Skelton Robinson, 1949.

Les Patineurs. Choreographed by Frederick Ashton, performance by the Royal Ballet. 2010, Opus Arte, 2011.

“Les Patineurs, part 1” [Joffrey Ballet]. YouTube, uploaded by markie polo, 2 Aug. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-OJz0V6h-X0&t=23s.

“Les Patineurs, part 2” [Joffrey Ballet]. YouTube, uploaded by markie polo, 2 Aug. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RmU7DCeK2w&t=57s.

“Les Patineurs, LCB, Singapore 1992”. YouTube, uploaded by Andrew Steven, 6 Apr. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=puxdJVP6zQg.

Quinton, Laura. “Ninette de Valois and the Transformation of Early-Twentieth Century British Ballet”. Precarious Professionals Gender, Identities and Social Change in Modern Britain, edited by Heidi Egginton, and Zoë Thomas, U of London P, https://read.uolpress.co.uk/read/precarious-professionals-gender-identities-and-social-change-in-modern-britain/section/9215c1f3-a47c-4d1f-8ca8-352d7e343414.

“Pre-war Television: March 5, 1937”. Radio Times Archive, http://www.radiotimesarchive.co.uk/television.html.

Reading, Charles. “Sadler’s Wells Personalities”. The Dancing Times, New Series, no. 314, 1939, pp. 131-38.

Richardson, Phillip. “The Sitter Out”. The Dancing Times, New Series, no. 314, 1936, pp. 135-38.

—. “The Sitter Out”. The Dancing Times, New Series, no. 356, 1940, pp. 463-67.

“Swan Lake, The Vic-Wells Ballet- 1937”. Madeleine’s Stage, https://madeleinesstage.co.uk/swan-lake-the-vic-wells-ballet-1937/. Accessed 13 July 2025.

Vaughan, David. Frederick Ashton and his Ballets. 2nd rev. ed., Dance Books, 1999.

Walker, Kathrine Sorley. Robert Helpmann: a rare sense of theatre. Dance Books, 2009.

Williamson, Audrey. Contemporary Ballet. Rockliff, 1946.