The year 2025 marks the 60th anniversary of Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet.

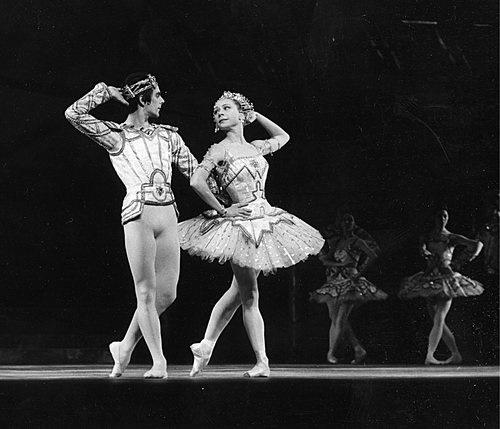

At the premiere in 1965, Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev famously received forty-three curtain calls (“The Royal Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet”). Since then the work has been staged regularly, filling the Royal Opera House. Moreover, despite the abundance of balletic Romeo and Juliets performed across the globe, as Emma Byrne of the Evening Standard points out, MacMillan’s adaptation is often considered to be the “definitive” ballet version of Shakespeare’s play.

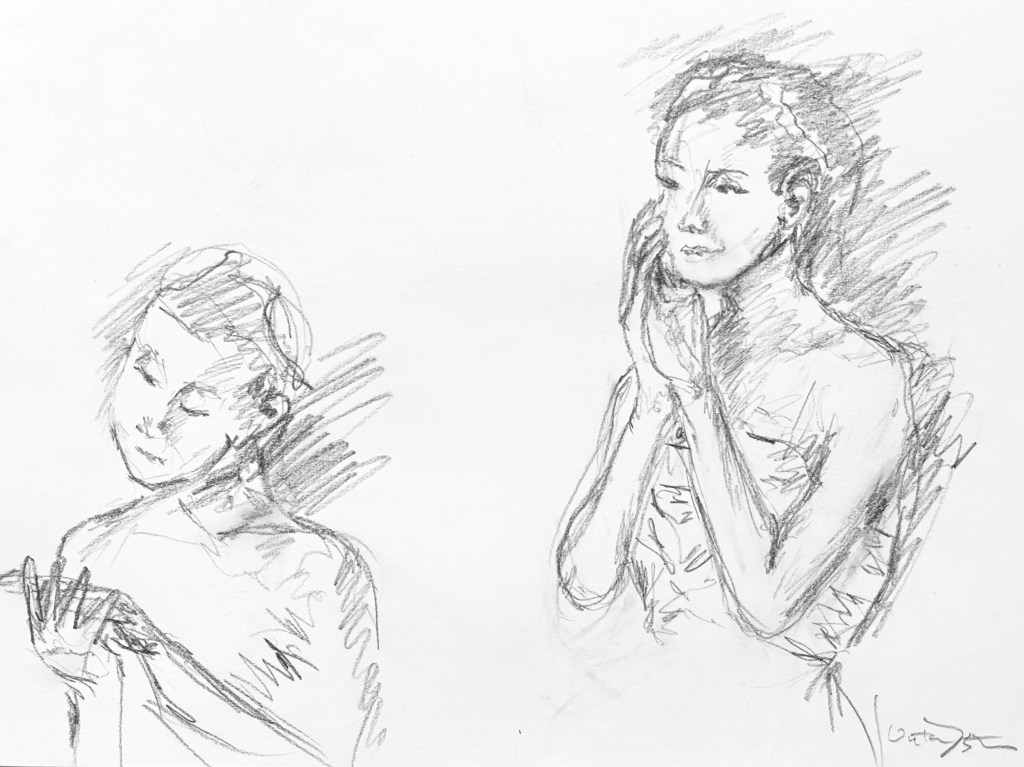

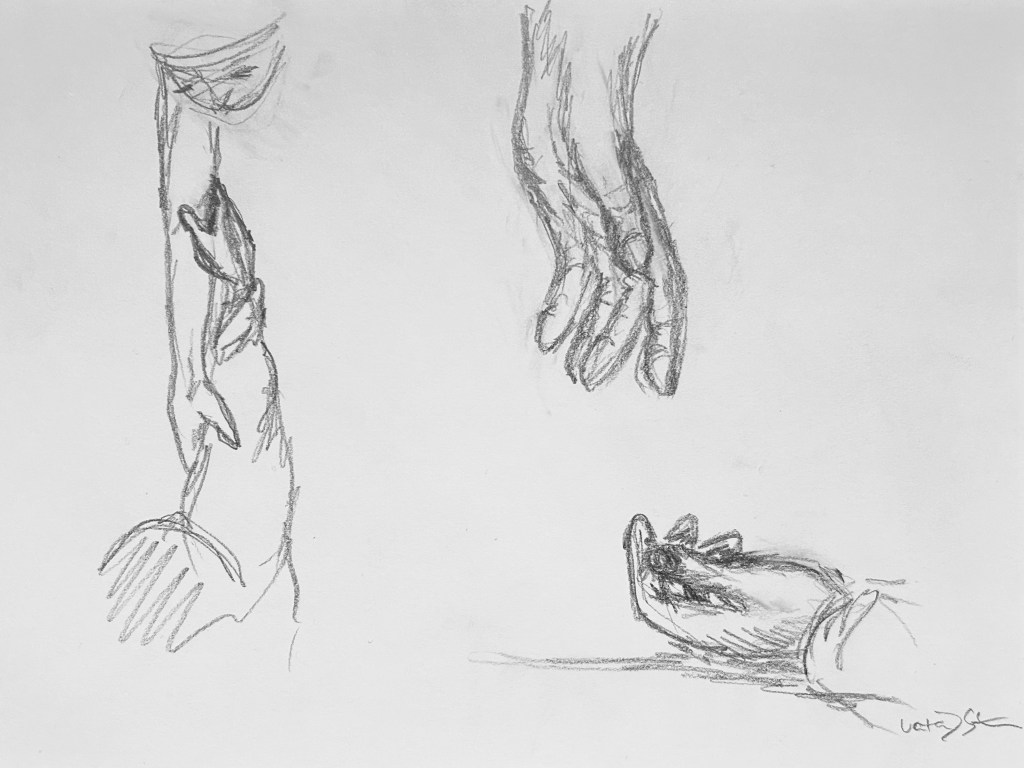

From 1966 to the present day MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet has also been screened in the cinema, on television, and since the 1980s reproduced on VHS tapes, then DVDs, and now on streaming services. This is the topic of our discussion below, originally written in 2022, and now updated, and enhanced with original artwork by Victoria Trentacoste of thinkcreatewrite.com.

Romeo and Juliet on Screen Now

Given the importance of this year’s anniversary in the history of MacMillan’s ballet, the announcement that a performance would be live-steamed in cinemas once again came as no surprise. In contrast, when a 2007 recording of Romeo and Juliet starring the celebrated dance partnership of Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta arrived in cinemas the following year, it caused quite a stir, as well as a debate about the advantages of watching ballet in cinemas (Wilkinson). Since then cinema screenings in the arts have become a regular occurrence, not only from the Royal Opera House but from, amongst other venues, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the Palais Garnier in Paris, and the National Theatre here in London. And no fewer than four live performances of MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet have been screened in cinemas since 2008, featuring the following principals: Lauren Cuthbertson and Federico Bonelli (2012); Yasmine Naghdi and Matthew Ball (2019); Anna Rose O’Sullivan and Marcelino Sambé (2022); Fumi Kaneko and Vadim Muntagirov (2025). Apart from this year’s offering (which will presumably be released in due course), all of these recordings have been made commercially available either on DVD or on Royal Ballet and Opera Stream, and all have been directed for the screen by Ross MacGibbon, former dancer with the Royal Ballet, and now a renowned filmmaker specialising in dance and theatre.

In preparation for our original Romeo and Juliet post in 2022 we studied all of the recordings available on DVD. However, for the purposes of our discussion below we focussed on only one of these recordings. We found it quite tricky to choose, but we decided that the ballet partnership of Rojo and Acosta made a neat parallel with the Fonteyn and Nureyev partnership featured in the Romeo and Juliet on Screen Then section of this post.

By the time of filming Rojo and Acosta were an established partnership in both the 19th century classics, particularly Giselle (Perrot/Coralli, 1841) La Bayadère (Petipa, 1877) and Swan Lake (Petipa/Ivanov, 1895), and in MacMillan’s Manon (1974), as well as Romeo and Juliet. Described as taking the Royal Ballet “by storm” when they joined the company (Acosta in 1998, Rojo in 2000) (Guiheen), over time they became known on stage as the “Brangelina of ballet” (Tan). This suggests that although they indubitably did not cause the sensation of Fonteyn and Nureyev (has any couple in the history of British ballet?), they were unquestionably a ballet partnership of glamour, and a force to be reckoned with. Further, they had received outstanding notices for their performances. John Percival, for example, claimed that Rojo “must be the best Royal Ballet Juliet for a quarter century or more, since Gelsey Kirkland’s guest seasons”, adding that Acosta was “on equally fine form”, while according to Sarah Crompton, their performances “absolutely gleam[ed] with greatness” (qtd. in “Reviews 2004-2007”). In contrast, with the exception of Bonelli, all of the other protagonists filmed in Romeo are home grown, so to speak, all having had at least some training at the Royal Ballet School; neither were their partnerships celebrated to the same extent. However, by the 2012 Bonelli-Cuthbertson performance, cinema screenings of ballet were well established, and consequently perhaps no longer needed the draw of an international star partnership.

By now you must be asking yourselves about still the most publicised screening of the ballet in recent years, that is, Romeo and Juliet: Beyond Words … which we have of course not forgotten. For their 2019 Beyond Words former Royal Ballet dancers Michael Nunn and William Trevitt held auditions, resulting in the cast being led by two more home-grown talents: Francesca Hayward and William Bracewell. Undoubtedly the reason for the additional publicity was that Nunn and Trevitt produced and directed an adaptation of the ballet filmed on location. Their choice of location was the Renaissance backlot of the Korda Studios in Hungary. Constructed for the TV series The Borgias, the backlot is a magnificent and atmospheric set of buildings, courtyards, piazzas, alleys and interiors depicting historical Italy.

Filming the ballet on location was of course not an original idea. As early as 1955, Lev Arnshtam directed the seminal Romeo and Juliet by Leonid Lavrovsky (1940) on location in the Yalta Film Studio. Perhaps more important for our discussion, however, is the film of Shakespeare’s play directed by Franco Zeffirelli. We know that MacMillan had been inspired by Zeffirelli’s 1960 Old Vic staging. Further, the naturalism emphasised by Zeffirelli in his direction lent itself well to an on-location filming, including the Palazzo Borghese in Rome, the streets of the medieval town of Gubbio, and the Basilica of St Peter in Tuscania. Therefore, this way of breathing fresh life into MacMillan’s choreography and bringing the ballet to potential new audiences seemed to us entirely compatible with the choreographer’s own vision for his work.

In all of the recent live recordings on DVD the familiar rich colour palette of Nicholas Georgiadis’ designs dominates: deep reds, browns and golds, with injections of white, noticeably in the costumes of the two Lovers. In contrast to this, Beyond Words is altogether brighter and livelier in its initial visual impact, opening as it does on the sun beaming down on a courtyard scene of hens and a dog, a busy servant, and a small child running off on some errand. Juliet’s room is no longer a minimally furnished vast stage space, but a chamber embellished with pale light drapes that let the sunshine in, and filled with various furnishings, including a chest, cushions, a settle, chairs and candles.

MacMillan’s ballet began life in 1964 when he was commissioned to create a short work for Canadian television. This work in fact became the Balcony pas de deux, which MacMillan created on his muses Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable. This duet was the beginning of the full ballet that premiered the following year in London. Given its place both within the narrative and as the culmination of Act I, it is of course one the ballet’s main climaxes; but for us, the fact that the rest of the work emerged from this pas de deux gives it a special significance.

At the start of the scene Tamara Rojo’s Juliet emerges from the darkness of the balcony, the whiteness of her skin and dress gleaming softly through the night air, and we think of Romeo’s wistful words …

But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?

It is the East and Juliet is the sun!

(11.2.2-3)

She looks down at the hand that Romeo touched when they first met in the Ballroom, brings her hands together and holds them to her cheek. Again, we hear the voice of Romeo:

See how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

Oh that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

(11.2.23-25).

Given that MacMillan, Seymour and Gable worked with Shakespeare’s text, it seems reasonable to assume that these gestures were integral to the original choreography, but even if not, we know that Rojo studied Shakespeare’s text in her preparation for dancing the ballet, thereby rendering her approach to creating her own version of Juliet faithful to the spirit of the work (“Tamara Rojo on being Juliet”). We also find that the resonances with Shakespeare’s soul-stirring verse, and the reference to their first meeting lend a palpable air of longing to the opening of the scene.

At the end of the scene Juliet returns to the balcony, only to kneel down immediately and reach for Romeo, who is straining up towards her. But despite their burning passion, their hands don’t quite meet—a reminder perhaps that the distance imposed upon them is simply too great; or maybe it is an expression of unfulfilled desire; or perhaps both. Whatever our feelings about this moment, it is also a foreshadowing of the tomb scene where Rojo’s Juliet lacks the strength to keep hold of Romeo’s hand as she draws her last breath.

In an interview after the Beyond Words premiere, Hayward talked about how important the set was to her understanding and portrayal of Juliet. At the start of the Balcony Scene music we see the Nurse (Romany Pajdak) brushing Juliet’s hair. Juliet seems preoccupied, restless. As she approaches her balcony, we watch her from behind, almost as if we are following her into another world. But the scene is softly aglow with the light of the moon, so there is no sense of Juliet lighting up the darkness; neither are there any noticeable gestures referring to Juliet’s first meeting with Romeo or to Shakespeare’s text. But what we are given here is a sense of being physically present in Verona, as we watch the Lovers through the foliage of the garden. And at the end of the scene not only do their hands touch, but they are able to hold one another’s forearms before letting go again. Although the scene is to us rather less poetic than the stage version, it recreates the sense of realism that MacMillan was so eager to effect in a work—a realism to which we have perhaps become too accustomed to fully appreciate.

At the end of the film our minds return to this moment of joy: looking through the grille enclosing the crypt, we witness Juliet’s failed attempt to reach Romeo’s hand. In close-up shot all we can see in the final moments are her hands dangling over the tomb, almost as if they were disembodied. It is well known that MacMillan wanted no sentimentality to be portrayed in this scene: “… the death scene was crucial to Kenneth. His lovers were not reunited in death. They did not die in each other’s arms” wrote Seymour (186). As far as MacMillan was concerned, the death of Romeo and Juliet was a complete waste of young life (qtd. in Seymour 186), and this ending seems to us a fitting indictment on all those involved in precipitating the death of the teenagers.

Another memory that Seymour writes about is the now iconic scene where Juliet sits alone and still on her bed in desperation until she resolves to visit Friar Laurence for help with her predicament. Sixty years after the premiere, this is still a suspenseful moment of high emotion in a live performance, a moment when we invariably reach for our opera glasses to experience more intensely Juliet finding a glimmer of hope through her despair. As if mimicking our opera glasses, in both the recordings we’re analysing the camera moves in close, so that we can witness the expressivity of Rojo and Hayward in their near stillness, watch the quickening of their breath, the agitation in Hayward’s face, and the transformation from Rojo’s dark mien to the return of light to her face. And sixty years after the premiere, this must surely still constitute a challenge for the ballerina to project her interpretation of Juliet’s emotions through the most economical of means. Rojo herself states, “The hardest thing is the moment when you sit in bed and you have no movement at all to express your feelings” (“Tamara Rojo on being Juliet”).

Romeo and Juliet on Screen Then

For commercial recordings of Romeo and Juliet from earlier years there is no problem of choice: as far as we are aware, there are only two. These are the film version made just one year after the creation of the work, starring Fonteyn and Nureyev, and the 1984 recording for BBC television featuring Wayne Eagling and a 21-year-old Alessandra Ferri.

We found comparing the two in terms of visual impact very interesting. Although recorded in Pinewood Studios, the film version attempts to simulate a theatre experience with the opening and closing of the curtains at the start and end of each act, and curtain calls at the end. Given that it was produced and directed by the film maker Paul Czinner, we would guess that the budget was quite substantial. In contrast, the quality of the television film is rather poor, far from the high definition to which we have now become accustomed. Although a sense of opulence is still conveyed with some imagination on the part of the viewer, the television production values are of the time, and we must confess that to us it is rather drab looking. This MacMillan may of course have appreciated in a way, given his love for realism in the theatre.

On the other hand, from the start the Czinner film blazes with colour like a Renaissance painting, with bright blues and highly pigmented reds, striking yellows and dazzling golds and greens vying for attention. For us these original sets and costumes provide an ideal frame for the kind of vibrancy that MacMillan had so admired in Zeffirelli’s Old Vic production of the play in 1960 and wished for his own ballet. In fact he told Georgiadis, who often attended rehearsals, that he wanted a Verona “where young horny aristocrats roamed the town full of romantic, adventurous spirits” (qtd. Seymour 181).

Just as there is such a dramatic contrast between the look of the two recordings, there are some equally alerting contrasts in the particular moments that we have discussed above in the Now section of this post.

When booking tickets at the Royal Opera House, we have always preferred to sit on the left side of the auditorium for this ballet, to ensure that we can watch Juliet on her balcony. There seems to be a substantial amount of freedom from performer to performer with regard to how she uses the opening music of this scene, and very likely ballerinas won’t even perform exactly the same movements from one performance to the next; so this is another moment when the opera glasses come out. Ferri appears with an air of blissful restlessness, looking up at the moon, down to her hands, over the balcony and up to the moon again. Leaning her elbows on the balustrade, the most telling moment is when she holds her hands to her cheek, swaying her body gently from side to side with an ecstatic smile on her face. But Fonteyn’s use of this moment of freedom to explore Juliet’s feelings we find almost disconcerting. As in the 2007 and 1984 productions, she emerges from darkness to light up like Romeo’s “bright angel” (Shakespeare 11.2 26, p. 37), after which she gestures slowly upwards with her right arm towards the moon. Although we know the moon to be significant to Shakespeare’s scene, in our opinion the gesture does not reveal much about Juliet’s thoughts and emotions. This was contrary to the intentions of MacMillan, Seymour and Gable who had “tried to find steps and gestures to express the characters’ state of mind” (Parry 279).

The scandal of the world premiere of Romeo and Juliet being given to Fonteyn and Nureyev in favour of Seymour and Gable, who had contributed so much to the rehearsal process, is well documented. Not only was Seymour cast as the fifth Juliet, but it was she who taught the role of Juliet to the other four ballerinas: “Margot … wanted to create her own Juliet”, she recalls (188). This is particularly noticeable in some movements near the start of the Balcony Scene that are reminiscent of “The Kingdom of the Shades” from Marius Petipa’s 1877 La Bayadère, which Nureyev had staged in 1963: supported pirouettes ending in arabesque accentuate Fonteyn’s classical line, and were presumably chosen by her for this reason. At the close of the scene Nureyev remains downstage right in a lunge, elegantly gesturing towards Juliet on the balcony as she reciprocates by unfolding her arm in his direction. This approach does accentuate the irreconcilable distance that the family feud has imposed upon the Lovers; but the poses strike us as symbolic, rather than reflecting the naturalism and urgent emotion that MacMillan was after. As Seymour put it during a coaching session on the Balcony Scene:

He wanted you to be a real pimply teenager, both of you, who bump noses when they first try to kiss and do all that sort of thing. They didn’t do it beautifully … it was a little awkward, and a little wonderful, and a little gawky and a little this and a little that. So try not to deal with it as if you’re some kind of ballerina.

(“Romeo and Juliet Masterclass”)

Another noticeable discrepancy that jars somewhat is Fonteyn’s choice of movement when her Juliet is trying to find a solution to her approaching marriage to Paris. Rather than sitting on the bed facing directly downstage, she kneels by the bed facing downstage left and mimics crying before raising her head and slowly moving her gaze to downstage right, almost as if watching herself rushing to Friar Laurence. Perhaps this worked at the time, but when the viewer is accustomed to the drama of being confronted with Juliet’s stillness face-on, it breaks the intensity of the moment.

Seymour recalls what a daring decision it was to reduce movement to a minimum at this climactic point in the narrative, and what a challenge it presented for her, but that MacMillan was convinced that she was capable of holding the audience (185-86). And his belief in Seymour was justified: audiences and journalists alike were struck by the audaciousness of the sequence, Seymour claiming that it “had a singularly terrifying effect on the scalp of balletgoers” (193).

Presumably it was a combination of Fonteyn’s celebrity status and the challenge presented by the innovative choreographic and dramatic ideas conjured up by MacMillan, Gable, and Seymour that persuaded the other Juliets to adopt Fonteyn’s approach to interpreting the choreography and character, resulting in MacMillan’s fear that his vision of the ballet would not be realised onstage (189). However, as the recording of Ferri’s 1984 performance testifies, MacMillan’s fears were ultimately unfounded. The Balcony Scene ends with Romeo and Juliet straining towards one another in their burning desire to touch one another’s hands just one more time before they part. Ferri’s Juliet sits on the bed facing the audience as Colin Nears’ camera zooms out, thereby emphasising her aloneness in the vast stage space that represents her room. And Ferri, who became such a long-standing interpreter of the role, showed no reluctance in the death scene to allow the weight of her body to hang in a precarious backbend over the sepulchre with no thought to elegance, unable to keep hold of Romeo’s hand. Fonteyn’s Juliet, on the other hand, dies holding onto Romeo’s arm and with her body carefully arranged so we can still see her face, and with little sense of the precariousness that might disrupt the ballerina image.

Ironically perhaps, the Czinner recording states overtly that the purpose of the film is twofold: to preserve the performance for a wider audience and as a record for posterity. For us, however, the importance of the film lies not so much in its preservation of the dancing of the two undisputed ballet stars of the era, but the way in which the reluctance of the performers to engage fully with MacMillan’s vision highlights the radical nature of MacMillan’s choreography seen both in performance and in the later films.

Concluding thoughts

Having grown up at a time when the only way to engage with ballet choreographies apart from seeing them live was through written materials, photos, LPs and the occasional television broadcast, we feel immensely privileged to have access to all of these recordings of MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet.

The films offer us an insight into the radical nature of the choreography, and ways in which the politics of power can have an impact on the nature of a choreographic work. We can also re-evaluate the work after a long period of familiarity and find new ways of appreciating it through the imaginative work of directors and new casts that bring the work to life again.

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

Byrne, Emma. “Romeo and Juliet review: an inspired choice for the Royal Ballet’s return”. Evening Standard, 6 Oct. 2021, www.standard.co.uk/culture/dance/romeo-and-juliet-review-royal-opera-house-b959020.html.

Guiheen, Julia. “Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta in “Romeo and Juliet” (2007)”. Pointe Magazine, 20 Nov. 2019, pointemagazine.com/tbt-tamara-rojo-carlos-acosta/.

Parry, Jann. Different Drummer: the life of Kenneth MacMillan. Faber & Faber, 2009.

“Reviews 2004-2007”. Tamara Rojo, 7 Mar. 2006, www.tamara-rojo.com/reviews-2004-2007/.

“The Royal Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet: 50 years of star-crossed dancers – in pictures”. The Guardian, 2 Oct. 2015, www.theguardian.com/stage/gallery/2015/oct/02/royal-ballet-romeo-and-juliet-50-years-of-star-crossed-dancers-in-pictures.

Seymour, Lynn, with Paul Gardner. Lynn: the autobiography of Lynn Seymour. Granada, 1984.

—. “Romeo and Juliet Masterclass: Balcony pas de deux”. Revealing MacMillan, Royal Academy of Dance, 2002.

“Tamara Rojo on being Juliet”. Dance Australia, 26 May 2014, http://www.danceaustralia.com.au/news/tamara-rojo-on-being-juliet.

Tan, Monica. “Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta: the Brangelina of ballet on chemistry, ageing and loss of innocence”. The Guardian, 27 June, 2014, www.theguardian.com/culture/australia-culture-blog/2014/jun/27/tamara-rojo-carlos-acosta-brangelina-of-ballet.

Wilkinson, Sarah. “Why Watch Ballet on the Silver Screen?”. The Guardian, 15 Aug. 2008, www.theguardian.com/stage/theatreblog/2008/aug/15/whyshouldipaytoseeprerec.