Akram Khan’s Giselle Revisited

If Tamara Rojo’s sole achievement during her years as Artistic Director of English National Ballet (2012-2022) had been the commissioning of Akram Khan’s Giselle, she would have made a tremendous contribution to the ballet repertoire. Such are our thoughts both before and after the Sadler’s Wells opening night of the production in September 2024.

Of course we have been watching the ballet since its first London run in 2016 and seen most of the casts. Treasured memories include multiple viewings of Tamara Rojo herself with the wonderfully human James Streeter; a particularly intense performance by Alina Cojocaru and Isaac Hernández, where they both seemed to take flight into another dimension; Crystal Costa’s final ENB performance, with the sensitive and expressive Aitor Arietta, and our first viewing of James and his wife Erina Takahashi performing together (last year in Bristol).

Revisiting the work after a period means seeing it afresh. We know that. But as the now-familiar stage action unfolds, we are surprised when a veil seems to lift from our eyes and we start to notice more clearly underlying patterns that bring an additional layer of emotional resonance to the piece for us.

From the gloom emerges the crowd of refugee Outcasts pressing against the Wall. From the crowd emerges a triangle of outliers: Giselle, a model of defiance and strength of will in the face of the Landlords; Albrecht, her lover, himself a Landlord, but one who spends time with the refugees to see Giselle; and the angry, arrogant, but fearful Hilarion, desirous of Giselle but desperate to improve his lot in life by bargaining with the Landlords. We start to realise that triangles in this work act as an omen. Conveyed through the most potent economy of means—space, eye contact and stillness—this is just the first of several dangerous triangles that mark key points in Khan’s staging.

Once seen and surely never forgotten is the Glove Scene. Bathilde, Albrecht’s fiancée, removes one of her gloves with deliberation and drops it on the floor for Giselle to pick up. Her cruel power game plays out in stillness: Giselle holds her rival’s gaze with confidence and defiance as she calmly returns the glove. But it is not Giselle who has retrieved the glove. No. The other character in this triangle is Hilarion. It is he who has stooped down to pick the glove up from the ground and has attempted in vain to make Giselle bow her head before Bathilde. He has managed to force the other Outcasts to bow down before the Landlords, but Giselle he cannot control.

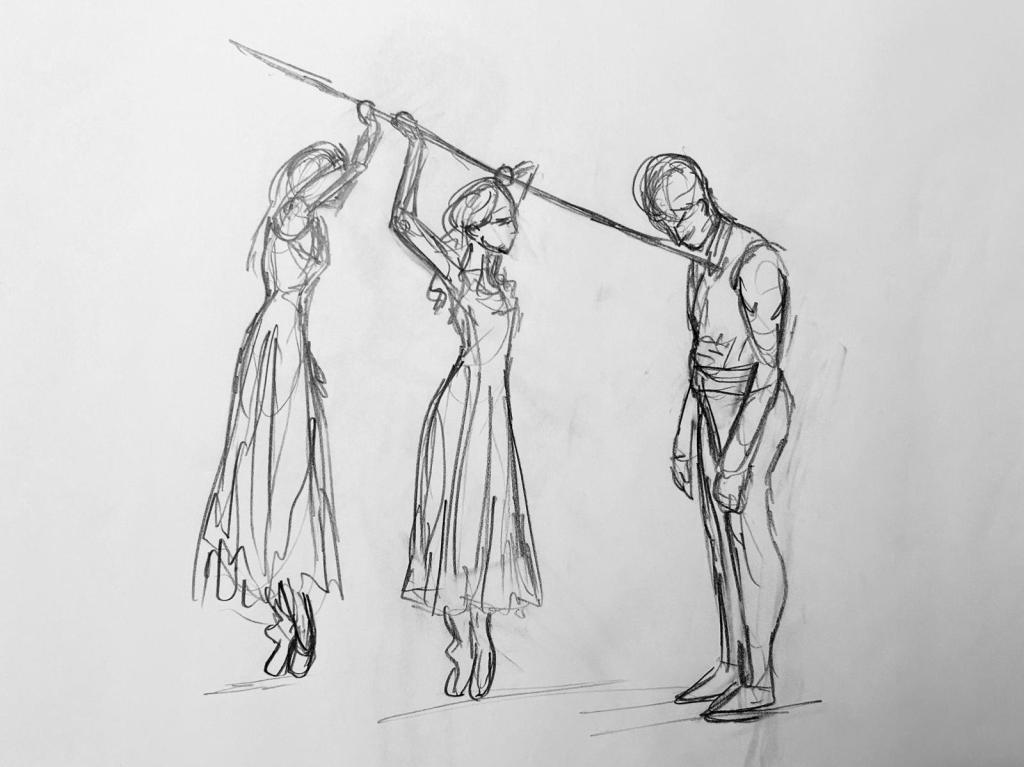

As Albrecht and Hilarion fight—a fight so palpable in its aggression, even though physical contact is limited—the chief Landlord circles slowly around them until his gaze reaches Hilarion’s eyes, a gaze of such force that it brings the confrontation to an abrupt end. Squeezing Albrecht’s jaw in the vice of his grip, the Landlord seals Albrecht’s fate with an angry kiss.

The fates of Giselle herself and Hilarion are sealed at the moment when triangular relationships collide into a deadlock. Giselle has dared to insert herself and her unborn baby into the “neat” triangle of the Landlord, Bathilde and Albrecht, that is, the triangle that will keep power in the hands of the powerful and keep it removed from the powerless. Giselle pulls Albrecht’s hand to her belly, holding it there so he can feel their bond. But feeling instead the glare of the Landlord and Bathilde’s penetrating eyes upon him, Albrecht wrenches his hand away, throwing Giselle to the ground. Then he literally turns his back on Giselle to walk off stage with Bathilde.

For us the words of First Soloist Katja Khaniukova, who has been involved in the ballet since its premiere, shine a light on this climax:

I believe that she’s dead from the moment when Albrecht left her, when he decided … when he just turned away … That’s the moment when she died inside.

The ensuing mad scene is the final straw for the Landlords, as it were. Giselle must be got rid of. And it is Hilarion who is tasked with the dirty work.

Our impressions of Act I lead us to conclude that the narrative of Khan’s Giselle can be traced through this series of triangular relationships, based on love, desire, power and control, that escalate to the crisis point of Giselle’s destiny.

In the final triangle of the ballet Giselle seems to regain some of her agency. It is she who cannot or will not pierce Albrecht through the heart with the cane, despite Myrtha’s urgent exhortations to do so. It is she who demands some grace time to relive moments of love with Albrecht. And it is she who pulls the cane from Myrtha’s grasp, thrusts it into herself and then Myrtha to connect them as they disappear back into the gloom. Giselle then holds Albrecht’s gaze for as long as she is able. Erina Takahashi, who has been dancing Giselle since 2016, gives us a sense of Giselle’s state of mind.

So one of the scenes that has a strong impact on me … is at the end of the ballet … the last pas de deux with Albrecht. At the end we are feeling each another and Myrtha takes us separate, but I decide to say to Myrtha “It’s ok, I’m coming with you”. … You have a last look to Albrecht to say goodbye to him, and then go away with Myrtha. That’s a very strong impact for me.

Days after the performance the magnificent score by Vincenzo Lamangna still haunts us. Lamagna’s reworking of the familiar love themes from Adolphe Adam’s original 1841 music have now taken on a life or their own: like a phantom they hover and linger, circle and circle without resolution. At a climactic moment the melody spirals into a dark wailing abyss as the Wilis perform their famous arabesques voyagés. With another woman dead at the hands of the Landlords, the vicious cycle of oppression continues without respite.

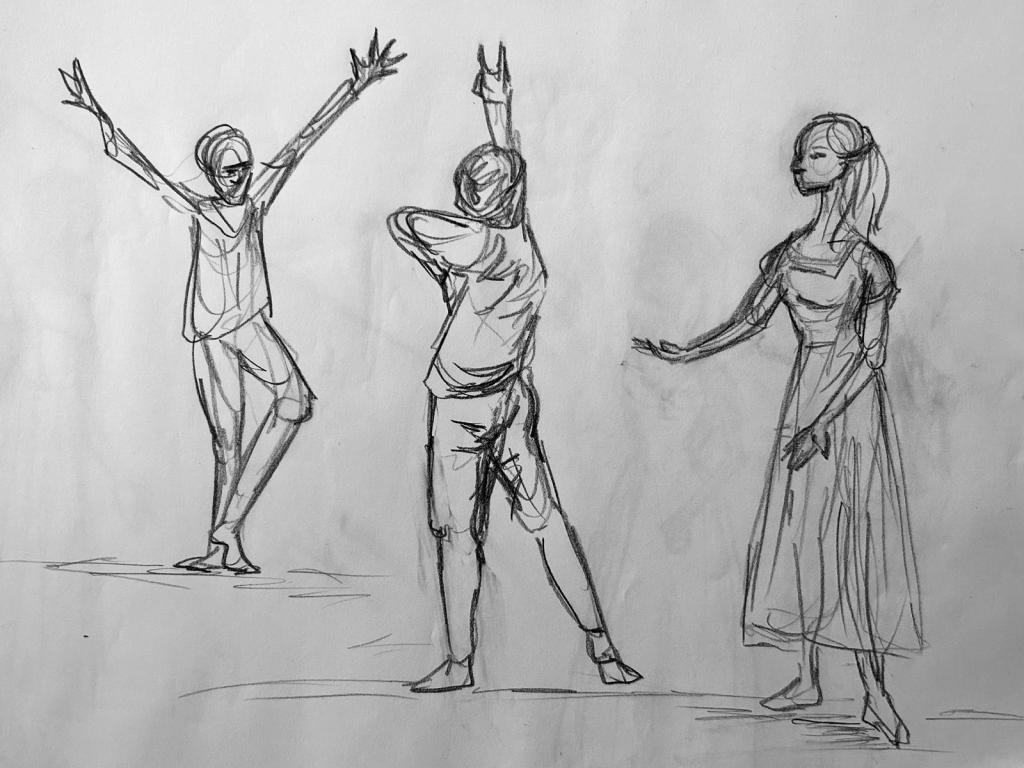

Ironically, in order to create such “bewitching” (Mackrell) performances of Outcasts, outliers and misfits, of divisive abuse of power, the Company must work together to produce cohesion in their dancing and storytelling. And in truth, we have never experienced a performance of this ballet where the effort and energy of such cohesion was not pouring from the stage.

We would like to thank our lovely friend Victoria Trentacoste for the beautiful hand-drawn illustrations 🙏

https://www.instagram.com/thinkcreatewrite/

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

Khaniukova, Katja. “Akram Khan’s Giselle: Katja Khaniukova’s favourite moments | English National Ballet”. YouTube, uploaded by English National Ballet, 23 Oct. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cM8nK0WYxs.

Mackrell, Judith. “Giselle review – Akram Khan’s bewitching ballet is magnificently danced”. The Guardian, 28 Sept. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/sep/28/giselle-review-akram-khan-english-national-ballet.

Takahashi, Erina. “Erina Takahashi on the ending of Akram Khan’s Giselle”. X, uploaded by English National Ballet, 18 Sept. 2024, https://x.com/ENBallet/status/1836358770542190633.