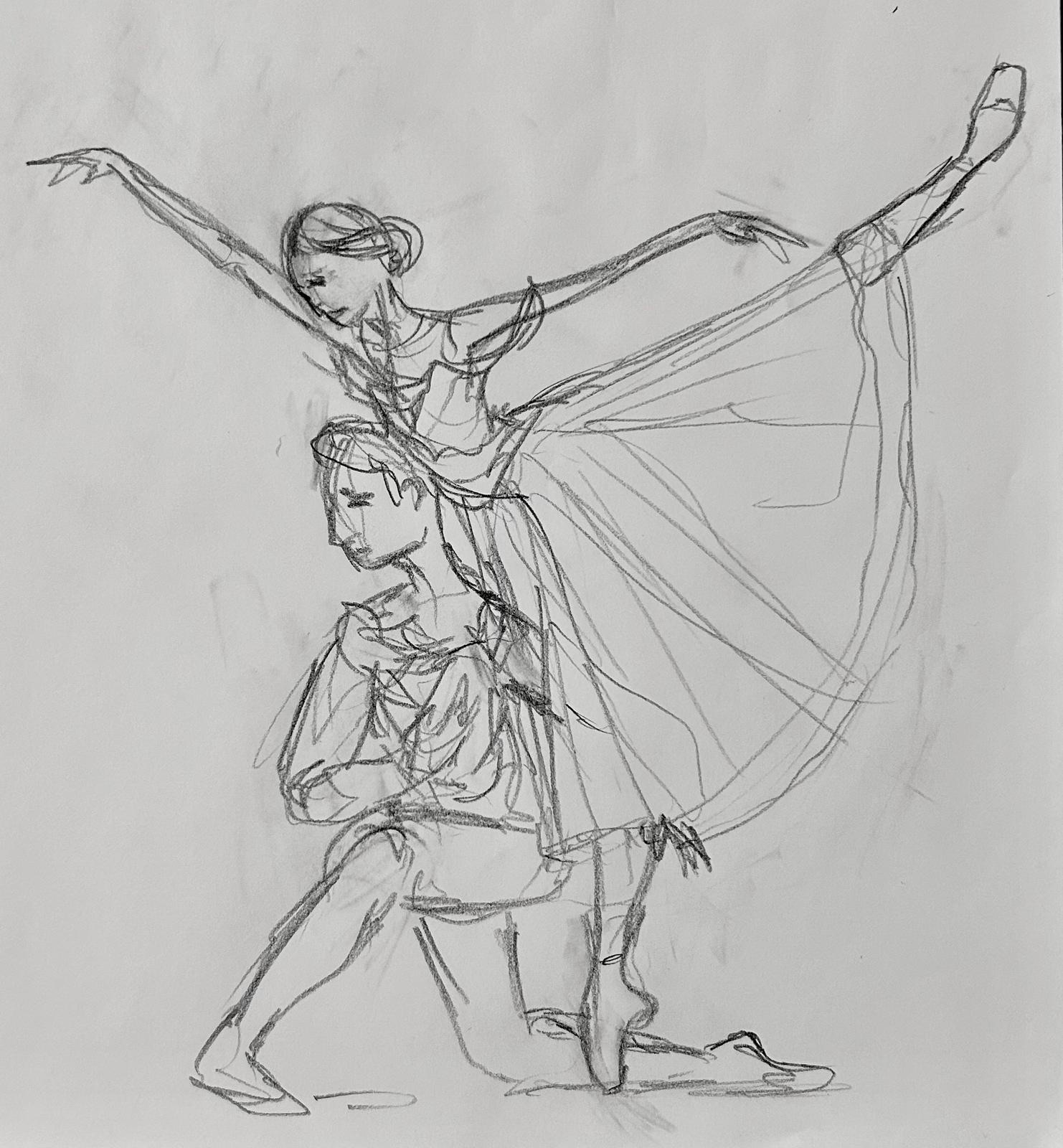

In January of this year we saw Erina Takahashi dance her final performance of Giselle in English National Ballet’s wonderful Mary Skeaping production. It was quite an occasion. Erina joined ENB in 1996, almost three decades ago, and attained the rank of Lead Principal in 2007. So she has been an integral part of the Company for a long time. We are thrilled that Erina is continuing her career with ENB as a repetiteur. Therefore we are issuing this new edition of our 2019 post “Giselle Productions Now & Then” with photos of Erina and original artwork by Victoria Trentacoste of thinkcreatewrite.com.

Giselle Now

As lovers of the ballet Giselle, first created in 1841 by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, we were beside ourselves with excitement when we learnt that Akram Khan was going to choreograph a re-envisioned adaptation of the Romantic work for English National Ballet. Our only concern was whether the Company would retain a traditional production of their work in the repertoire. Fortunately this fear was soon allayed when Artistic Director Tamara Rojo announced that Mary Skeaping’s Giselle would be revived in the very same season as the world premiere of what turned out to be a most extraordinary retelling of the work in an age of refugee crises and concerns about increasing social inequality and injustice both in the UK and globally.

This autumn, three years after the premiere of Akram Khan’s work, it is an ideal time for us to revisit Giselle. Not only has Khan’s adaptation returned to Sadler’s Wells, but two additional stagings are being shown in the same theatre: both Dada Masilo’s 2017 feminist reading of the work, which draws on her South African heritage, in October, and David Bintley and Galina Samsova’s 1999 Giselle for Birmingham Royal Ballet in November. Therefore, in this post we’re focussing predominantly on productions, rather than on what individual dancers bring to the role of Giselle, as we did in our first Giselle Now & Then post.

As you may know, while maintaining the broad outline of the plot, Khan and his dramaturg Ruth Little have based their narrative on a community of migrants who have lost their jobs in a garment factory and are now reduced to providing entertainment for the cruel Landlords (who replace the aristocrats of the original libretto). In Act II the ghosts of dead Factory Workers wreak revenge on those who caused their death through the appalling working conditions in the factory.

When watching an adaptation, be it in the same medium, or book to film, play to ballet, the question of characterisation is always an intriguing one. There has been substantial discussion about the roles of Hilarion and Giselle herself. While Hilarion is absolutely crucial to the plot, in traditional versions he is not given extensive stage time or activity. In contrast, Khan’s Hilarion is a major character in terms of the stage action, and complexity of the role, as well as being a lynchpin in the storyline. A climax to Act I is the altercation between Hilarion and Albrecht, where they circle around one another like two stags fighting over their territory in a ritual of dominance creating a palpable tension with their glaring eyes drilling into one another. Hilarion is at the same time obsequious with the Landlords, supercilious with Albrecht and controlling with his fellow migrant Factory Workers. His skewed love for Giselle is bound to end in catastrophe.

Giselle herself is depicted by Khan as a leader (“Akram Khan’s Giselle: discover the main characters”); her pride and defiance are writ large when she refuses to pick up the glove that Bathilde has deliberately dropped, and stubbornly resists bowing her head to the Landlords. Khan sees Giselle as an optimist in the face of the disastrous closing of the factory and consequential unemployment, so she has no need to kowtow to the Landlords. She is also in love and expecting Albrecht’s child, so she has broken the rules and rocked the boat of the precious status quo that Hilarion is so eager to hold in balance.

Because of Hilarion’s centrality to Act I and the waywardness of his character, he seems to us to be a counterpart to Myrtha. Dramaturg Ruth Little describes Hilarion as “both sinning and sinned against” (“Akram Khan’s Giselle: discover”). Luke Jennings once found a libretto for a ballet about Myrtha’s backstory that accounts for her transformation from a loving, joyful and compassionate young woman to a vengeful wraith (“Who was Myrtha?”), and we can imagine reasons for Hilarion’s behaviour and his need to do anything to survive.

The 1841 Giselle is driven by dualisms: the daylight of the familiar village is pitted against the unknown of the dark forest; the poverty of the peasants is confronted by the blatant wealth of the aristocrats; a human community of corporeal beings is juxtaposed with the world of ethereal Wilis, where the relationship between flesh and spirit, body and soul is explored. Because of the spiritual element, Tamara Karsavina has referred to it as “a blessed ballet or an holy ballet” (A Portrait of Giselle). The spirit world is defined by a specific style of dancing, la danse ballonnée with its fleet lightness and Romantic tutus that balloon out to create the illusion that the dancers are hovering in the air. As Albrecht moves towards Giselle and fails to catch her, as she floats heavenwards in lifts and reaches away from Albrecht in arabesque, his longing for her is constantly met with confirmation of her unattainability. One of the reasons that Tamara Rojo chose Khan as the creative artist for this project was because of “the spirituality of the theme” and her belief that “he could find a different way of putting that on stage” (“Akram Khan’s Giselle: the creative”). The corporeal and ethereal worlds are clearly pitted one against the other by Khan, but the effect is strikingly different…

From the moment the curtain opens we sense the physicality of the dancers’ bodies as they push with all their might against a huge overwhelming wall (designed by Tim Yip).

Later, working as a group, they become the looms of their trade, mechanical pulsating machines; at other times they run in droves, almost like animals, as they escape their circumstances in search for new homes. In the radiant, sometimes playful, Act I duet between Giselle and Albrecht they orbit around one another and visibly enjoy their repeated moments of physical contact. Tenderly they touch one another’s head, neck, sternum, shoulders and palms, and Giselle places Albrecht’s hand on her abdomen to feel their child growing within her.

But the most intimate form of touch is when they touch one another’s faces with their hand – a movement reserved in Khan’s culture for husband and wife (Belle of the Ballet).

The Wilis of Act II wear pointe shoes, as a tribute to the Romantic tradition and the connection between pointe work and the notion of the otherworldly within that tradition. Moreover, the iconic scene where the Wilis cross one another in lines performing arabesque voyagé en avant is replicated. Originally this displayed their domination over the forest; in this case they preside over the abandoned factory. But these eldritch factory Wilis pound their canes threateningly and relentlessly into the ground, suggesting a less binary approach to the connection between flesh and spirit, the corporeal and ethereal, soul and body in this rendition of Giselle; and Giselle’s body is literally dragged into the factory by Myrtha – she may be dead, but she is in no way insubstantial.

This connection between body and spirit is demonstrated at its most poignant in the Act II duet between Giselle and Albrecht. For us Jennings’ description of Giselle’s state in Act II rings true: “She’s not dead, but she’s not quite alive, either” (Akram Khan’s Giselle review – a modern classic in the making). The choreography for Giselle and Albrecht’s duet is physically intimate, the closeness of the bodies more continuous than in the Act I pas de deux. As they wrap themselves around one another, their touch is more sustained and prolonged. It is this very physicality that suggests to us that their souls inhabit the same realm. There are fleeting moments where Giselle seems to evaporate from Albrecht’s embrace, as if in memory of Giselle of old. But her body is often limp, no longer able to resist the force of gravity, so Albrecht bears her weight and seems to try and woo her spirit back through the warmth of his body. At one extraordinary moment he draws her up from the ground using the power of her hand on his face, as if the bond between them will return her to life, but she almost immediately sinks back down again. Despite the bond Giselle pushes his hand away from her stomach – a reminder that their child has died within her. This is far from Romanticism’s trope of representing the spiritual as insubstantiality of body. A final touch of the hand on the other’s face is the last instance of physical contact. Their final prolonged gaze at one another is so intense that Albrecht fails to notice the wall descending. This ultimate physical separation in the face of the unassailable wall is gut-wrenching.

Giselle Then

The success of Khan’s Giselle with both critics and audiences in no way diminishes the power of traditional productions, so in this section we are discussing three traditional versions of Giselle performed by three major British ballet companies: David Bintley and Galina Samsova’s staging for Birmingham Royal Ballet, Peter Wright’s Royal Ballet production, and the version mounted by Mary Skeaping for London Festival (now English National) Ballet. Even though they present “standard” versions of the narrative and choreography, there are differences in design, staging, characterisation and movement style. These differences may initially seem slight, but on closer inspection they have a significant impact on performances and enable this 1841 Romantic ballet to maintain its freshness, and to continue to capture the imagination of the audiences.

When the Bintley-Samsova production of Giselle was first staged in 1999, Bintley expressed the objective of creating a “proper” Giselle (Marriott), meaning that he wanted to recreate some of the excitement felt by the 1840s audiences (Mackrell “Giselle: Birmingham”). Part of this excitement was instigated by the designers’ realistic depiction of Giselle’s two contrasting worlds, including live animals in Act I and Wilis “flying” on wires in the second act. Consequently, one of the elements that was chosen as a focus was the visual element.

For this mounting of the work designer Hayden Griffiths created a waterfall, vineyards and mountains as the background for Act I, an environment that David Mead likens to “a Victorian painting come to life”. The waterfall may also remind viewers of William Wordsworth’s The Waterfall and the Eglantine (1800), thereby making a satisfying connection with Romantic literature. The verisimilitude of Act I includes “a pig’s bladder football … a dead hare, two live beagles and a real horse” (Mackrell “Giselle: Birmingham”). The village is also brought to life by the inclusion of children in the cast (because why wouldn’t a village have children?) and by ensuring that the dancers emphasise the individuality of each villager. The bustling liveliness of this act, enhanced by the bright colours of the costumes, provides a striking contrast with the ballet blanc of Act II, with its “flying” aerial Wilis and its ruined abbey, in keeping with the tastes of the Romantic audiences, who relished the successful theatrical fashioning of the mystical and otherworldly. David Mead captures the atmosphere: “Gothic arches soar heavenwards above the ruined choirs. Lit by a full moon, peeking through what is left of the windows, it is spookiest of atmospheres”.

The waterfall of the first act is particularly significant, as water is an essential element in the legend of the Wilis – in Heinrich Heine’s Über Deutschland, one of the sources used for the original libretto of Giselle, Heine explains that their hems are constantly damp, as they dwell close to or even on the water. In Giselle; or The Phantom Night Dancers, the play based on the ballet that was produced in London shortly after the ballet’s premiere in Paris, the inclusion of “Fountains of Real Water” in Act II provided a major attraction and was therefore highlighted on playbills in no uncertain terms (Morris 53). Therefore, it’s interesting that Hanna Weibye incorporates water imagery in her writing to convey the effect of the corps de ballet as the Wilis in Peter Wright’s production for the Royal Ballet, to convey the impression that they create: “In John Macfarlane’s creamy Romantic tutus they cross the stage in serried ranks like swells on the open ocean, seemingly unstoppable” (“Giselle, Royal Ballet Review”).

It is this staging of Giselle by Wright for the Royal Ballet that is undoubtedly the most celebrated British production of the ballet. Wright has been producing Giselle since as long ago as 1966. We were fascinated to discover that when he first saw the ballet in the 1940s, he could not take it seriously. Once he had witnessed Galina Ulanova perform the title role on the Bolshoi Ballet’s first visit to London, however, he understood its potential; subsequently when John Cranko asked him to produce it for Stuttgart Ballet, Wright discovered (as we do!) that the more he researched, the more fascinated be became (“Getting it Right”). The current production is the second version that Wright has created for the Royal Ballet, and they have continued performing it regularly since 1985.

Wright’s approach to producing Giselle was to ensure that the characters and the drama made complete sense in his mind. To this end he made Bathilde into a more haughty, even heartless, character than she was in the original libretto, thereby creating a more sympathetic portrayal of Albrecht. This characterisation is often commented on by critics (Jennings “Giselle Review”; Mackrell “Giselle review”; Watts “An indelible performance”). Jennings’ comments on Olivia Cowley’s performance is particularly telling: “Realising that Albrecht has broken the village girl’s heart, Cowley’s Bathilde appears not so much wounded as faintly nauseated”. For Wright it is also essential that Giselle commits suicide, rather than dying of a broken heart, in order to account for her burial in the woods, outside the bounds of the churchyard and therefore unprotected from the Wilis (Monahan).

As in the case of Birmingham Royal Ballet’s production, design is a feature of the work that is essential to the creation of atmosphere, which has been described as “eerie”, with a “threatening” (Weibye) and “brooding” forest (Jennings). Macfarlane demonstrates a different approach to that of Griffiths, with a more uniform colour palette, but Graham Watts’ vivid description of the Act II décor shows how imaginative design can recreate an atmosphere by bringing new ideas to work that conjure up fresh images in the minds of the audience:

The woods … with their uprooted trees and a ceiling of scrambled, entwined branches provide the perfect lair for the ghostly Wilis to take their revenge on the carefree men who foolishly pass by in the dead of night (“Review: Royal Ballet in Giselle”).

And now to our favourite traditional Giselle …Like Peter Wright, Mary Skeaping spent years researching the ballet, but she also had the added advantage of dancing in Anna Pavlova’s company, when Pavlova herself was performing Giselle. In addition, Skeaping saw Olga Spessivtseva dance the role, and she received a great deal of support and guidance from Tamara Karsavina to help with her first staging of the ballet in 1953 for the Royal Swedish Ballet. In 1971 Skeaping mounted a production on London Festival Ballet (now English National Ballet), which is their current traditional Giselle. Undoubtedly the most authentic of the British versions, this production is probably exceeded in authenticity internationally only by Pacific Northwest Ballet’s 2011 reconstruction based on primary sources including two 19th century notation scores and the research of historian Marian Smith’s (“Giselle”).

One of the reasons we favour this production is pure sentimental nostalgia – in particular memories of Eva Evdokmova and Peter Schaufuss as the protagonists, Maina Gielgud as Myrtha and Matz Skoog in the Peasant Pas de deux, as well as the first performance of Natalia Makarova and Rudolf Nureyev dancing the ballet together. However, we are also fascinated by the impact of recreating period style, so evident in the curved asymmetrical port de bras and posture of the Wilis. It draws us into another era with its distinctive aura, “antique sense of the supernatural” (Mackrell “Giselle: Coliseum”) and restored sections, such as the complete Pas de vendages for Giselle and Albrecht. Giselle’s solo in this particular section gives a taste of a more authentic Romantic ballet style with its skimming terre-à-terre petit allegro, the batterie and ballon and quick changes of direction, all enhanced by gentle épaulement. Not only do we appreciate the understated virtuosity of such passages and the way they extend our understanding and knowledge of ballet, but when we watched performances by English National Ballet in 2017, we were struck by the contribution the full Pas de vendages makes to the dramatic climax of Act I. In comparison with the truncated version that is generally presented, the full Pas brings all the focus of both the onstage audience and the audience in the auditorium, to Giselle and Albrecht. It is playful and tender in its inclusion of the usual game of kisses, but also in the joie de vivre of the dancing style. Consequently, it distracts us from the plot, giving no warning or sense of the impending disaster. When Hilarion suddenly challenges Albrecht, it seems to cut like a razor through the celebrations. After such idyllic moments of love witnessed by her community, Giselle’s isolation in her distress is all the more raw and brutal. Perhaps it was this dramatic effect that inspired Bintley and Samsova to reinstate some of the usual musical cuts to their interpretation of the work, particularly with Samsova’s personal experience of dancing the title role in a number of different productions.

In our opinion all of these productions are relevant today. Tamara Rojo herself highlights the impact of the social context on people’s behaviour when their actions are driven by their emotions (“Akram Khan’s Giselle: The Social Context”), a theme that is of course evident in both the 1841 Giselle and the 2016 reinterpretation. Writing of the Royal Ballet’s production Hannah Weibye considers the added import of the ballet in the #metoo era, emphasising the themes of “abuse of power for sexual gratification” and questioning whether Albrecht deserves Giselle’s forgiveness. Khan’s interpretation of Giselle is a monumental work of art in its own right. As an adaptation, moreover, it provides us with a new lens through which to watch the Romantic work, find fresh insights, new emotional resonance, and to appreciate once again its own singular portrayal of love, betrayal and the beautiful, dangerous undead.

© British Ballet Now & Then

References

“Akram Khan’s Giselle: the creative process”. YouTube, uploaded by English National Ballet, 4 Oct. 2016, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cs2nsC_pchw. Accessed 17 Sept. 2019.

“Akram Khan’s Giselle: discover the main characters”. English National Ballet, http://www.ballet.org.uk/production/akram-khan-giselle/. Accessed 17 Sept. 2019.

“Akram Khan’s Giselle: the social context”. YouTube, uploaded by English National Ballet, 7 Oct. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Amlg-vPC9xU. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

Giselle: Belle of the Ballet, directed by Dominic Best, British Broadcasting Corporation with English National Ballet, 2 Apr. 2017.

“Giselle”. Pacific Northwest Ballet, 2019, https://www.pnb.org/repertory/giselle/. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

Heine, Heinrich. “Elementary Spirits”. Giselle. Programme. Royal Opera House, 2001.

Jennings, Luke. “Giselle review – uncontestable greatness from Marianela Núñez”. The Guardian, 28 Jan. 2019, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/jan/28/giselle-review-royal-ballet-marianela-nunez. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Mackrell, Judith. “Giselle: Birmingham Hippodrome”. The Guardian, 4 Oct. 1999, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/1999/oct/04/artsfeatures2. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

—. “Giselle: Coliseum”. The Guardian, 12 Jan. 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2007/jan/12/dance. Accessed 17 Sept. 2019.

—. “Giselle review – Muntagirov and Nuñez display absolute mastery”,The Guardian, 24 Mar. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/mar/24/giselle-review-muntagirov-and-nunez-display-absolute-mastery. Accessed 17 Sept. 2019.

Mead, David. “Birmingham Royal Ballet: Giselle”, Critical Dance, 21 June 2013, criticaldance.org/birmingham-royal-ballet-giselle/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Monahan, Mark. “Getting it Right”. Royal Opera House, http://www.roh.org.uk/news/getting-it-right-peter-wright-on-his-production-of-giselle. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Morris, Mark. “The Other Giselle”. The Creation of iGiselle, edited by Nora Foster Stovel, U of Alberta P, 2019.

A Portrait of Giselle. Kultur, 1982.

Watts, Graham. “An Indelible Performance”. Bachtrack, 21 Jan. 2018, https://bachtrack.com/review-giselle-royal-ballet-royal-opera-house-london-january-2018. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019.

—. “Review: Royal Ballet in Giselle”. LondonDance, 19 Feb. 2011, http://londondance.com/articles/reviews/giselle-at-royal-opera-house-3506/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019.

Weibye, Hanna. “Giselle, Royal Ballet Review”. The Arts Desk, 20 Jan. 2018, https://theartsdesk.com/dance/giselle-royal-ballet-review-beautiful-dancing-production-classic-good-taste. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019.

“Who Was Myrtha?”. Luke Jennings, Thirdcast.wordpress.com/2016/04/12/who-was-myrtha. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019.