We are a tad nervous. Northern Ballet is one of our favourite companies: we’ve travelled out of London to watch them perform Cathy Marston’s Jane Eyre and Victoria, as well as David Nixon’s Cinderella and The Great Gatsby. But this is Romeo and Juliet, and over the years there has been such a plethora of productions to see in this country, and even a cluster of celebrated versions created for, or at least staged by, British companies: English National Ballet have staged both Rudolf Nureyev’s and Frederick Ashton’s choreographies, Scottish Ballet John Cranko’s, and of course both Royal Ballet companies the iconic adaptation of Shakespeare’s play by Kenneth MacMillan, often described as the “definitive” Romeo and Juliet ballet (Byrne; Watts). Having been watching it since our teens, it is the Romeo with we are most familiar, the one that is indelibly seared on our memory.

How is it possible to compete with these celebrated works? We did in fact once see Northern Ballet’s production, which was choreographed by Massimo Moricone, and directed and devised by the dancer and actor Christopher Gable, who famously created MacMillan’s Romeo in 1965. But that was long ago, in the 1990s, when it was new, and our understanding of adaptation not as developed as it is now. We have read positive reviews, and we enjoy the conducting of Daniel Parkinson (Associate Conductor), as well as the dancing of members of the cast we are about to see: Dominique Larose (Juliet), Joseph Taylor (Romeo), and Rachael Gillespie (one of Juliet’s Friends). So, tentative as we are, let’s see what happens …

At first the scale of the work bothers us slightly: the market scenes are not teeming with people, and surely the ball is a rather slight gathering for a family as proud and powerful as the Capulets. But let’s shift our watching a bit and think of the stage action more as symbolic than realistic … There are other ingredients that bring the work to life. There are children in the marketplace (not all choreographers have followed August Bournonville’s enthusiasm for including children in the villages and towns that provide the setting of their narratives); there are great swaying, streaming carnival pennants that fill the space and add energy to the movement.

But what is most noticeable about the first fight scene is its humour. Montagues and Capulets jump on each other’s backs. There are fisticuffs. Lord Capulet tries to throttle his rival Montague. It’s all a bit uncouth. And there seems to be more flag waving and stick wielding than real intention to kill, despite the menacing posturing of the Capulets. Lethal weapons are scant.

Nonetheless, this first fight ends on a note of strange tragedy. A child dies and is held up by Prince Escalus for all to see. It seems a bit out of place amidst all the raucous behaviour. But again, thinking of it on a symbolic level, it functions as a forewarning of events to come.

Similarly, the Ballroom Scene, while relatively small in scale, is rich in action—so much so that it is quite a challenge (albeit a pleasurable one) to pick up on all the narrative detail. Our eyes roam around the stage to follow all the activity … Once he has spotted Juliet, Romeo moves around and across the space, as if drawn to her by an invisible thread. There are some shenanigans going on between Lady Capulet and her Nephew Tybalt in the background, which seems to cause some tension with Lord Capulet. And joy of joys, Juliet’s friends have personality—their function is definitely not simply to frame Juliet as the ballerina, but to convey something of the excitement and sheer pleasure of youth. They flit around the stage, eagerly watching the dancing, animatedly “chatting” amongst themselves, with Juliet’s Nurse, and with the Guests; they are prominent in the dancing with the Guests and with Juliet. And their thrill at being at the ball ratchets up a notch when they notice, all aflutter, the instant and magnetic attraction between Juliet and Romeo.

The hustle and bustle of the ballroom dissolves into dark stillness as a pool of soft light creates Romeo and Juliet’s new world of radiant and tender love, a love that is also pitted against the escalating friction between the aggressive Tybalt and mapcap Mercutio.

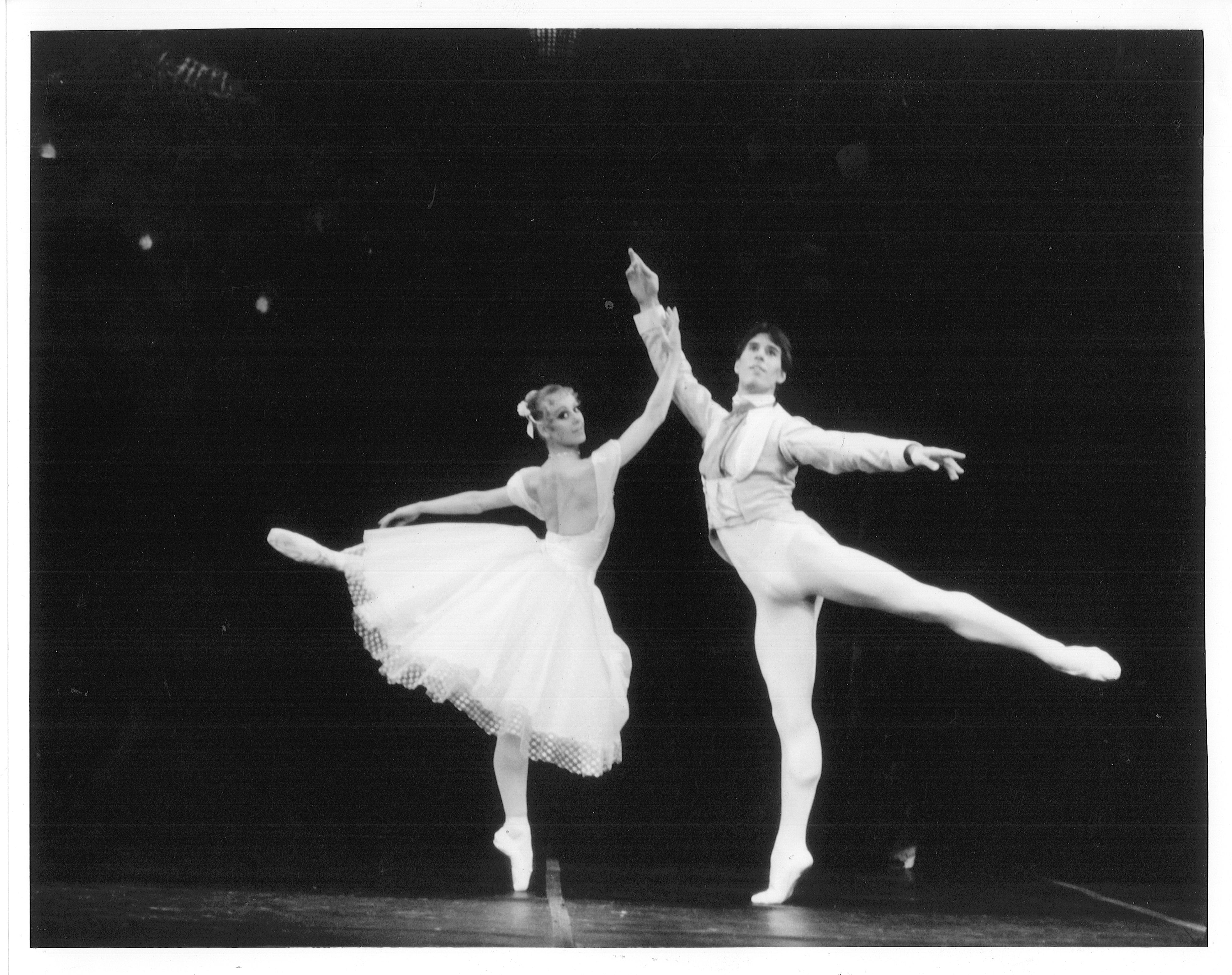

And now to the climax of Act I … The sets that separate the protagonists as the curtain opens on the first scene is now used to explore their desire for one another before they come together in their duet. At the start of the scene their breathless anticipation is palpable. Juliet above and Romeo below, they lean their bodies against the balcony, feeling its surfaces with sensuous touch, like a surrogate lover. Now moving around the stage together, their touch is reciprocated: they stroke one another’s hair, embrace, lean on one another and eventually kiss. Although the heady sweep of MacMillan’s choreography is still so alive in our minds, there are moments in the choreography before us where we see the movement follow Sergei Prokofiev’s score in a different way, as their bodies open and close, rise and fall with the melody.

And so to Act II … The light-hearted, comedic tone resumes, with jocund carnival dancing, while Romeo sets himself up for a good ribbing as he wanders the town square in a state of swooning reverie, followed by bawdy fun with Juliet’s Nurse when she brings Romeo his letter from Juliet. Even the fight between Tybalt and Mercutio begins more as derring-do than any serious intention to wound, let alone cause a mortal wound. Mercutio goads his opponent by waving Tybalt’s own gloves in his face, spinning, leaping and cartwheeling around him, like an acrobat. This ridiculing is too much for the vain and vicious Tybalt, who avails himself of a metal claw to strike out at Mercutio. And suddenly there is Mercutio impaled on the wall stabbed by his own dagger.

The duel between Romeo and Tybalt is of an utterly different order to all the fighting that precedes it. Right from the start both parties wield their lethal swords, one in each hand, fighting to the death. The clash of metal and the speed of movement expose the emotional intensity of this fight. But the violence culminates not only in the anticipated thrust of Romeo’s sword: the two men seize one another’s throats, with the result that Romeo kills Tybalt with his bare hands around Tybalt’s neck. The murder of Mercutio has flipped comedy to tragedy, play fighting to murderous violence. Sheets of rain cascade down from the heavens, with thunder and lightning, closing the act like an echo of Mercutio’s curse “A plague a’both your houses!” (3.1.106).

In the final act, the gawky child whose feet dangle from the bed is jolted into womanhood. We watch this transition with awe. The ferocity with which Juliet rips off the signature Capulet red and black apparel establishes her independence. Completely alone on the stage and in life, betrayed by her Nurse, in conflict with her Parents, her Cousin killed by her exiled Husband, Juliet has to make the decision that will determine the rest of her life. Shakespeare leaves us in no doubt about Juliet’s fears of what may transpire if she decides to take the potion. She imagines the “foul mouth” of the tomb, Tybalt “festering in his shroud”, “loathsome smells”, and “madly play[ing] with my forefathers’ joints” (4.3.34-51).

We watch Juliet dance a pas de deux in this scene, with the vial of sleeping potion replacing her partner. Dancing a pas de deux, her aloneness is all the more poignant: by rights she should be dancing with her husband on the first joyful morning of their marriage. She holds the vial close to her body, away from her body, moves it in circular motions around her—in front, above, behind her—turning, bending, swaying, twisting as she explores the space around her. She may be making a decision, but the vial seems welded to her very being, as if fate has decided for her.

Lady Capulet instructs the Nurse to see to Juliet’s body. After the warm, playful exchanges between Juliet and her Nurse, after the sharing of confidences and the Nurse’s fierce defence of Juliet in the face of Lord Capulet’s rage at his Daughter’s flagrant disobedience (more striking in this version than others, we feel), the Nurse’s deft, uncompromising, seemingly detached, stripping of the bed and rearranging of Juliet’s body conveys its own peculiar sense of brutality.

The violence of this work strikes us again in the Tomb Scene when Romeo’s response to Paris’ assault on him with a dagger is to smash Paris’ head against the wall—the nearest, most immediate weapon to hand. Romeo’s grief again manifests itself in raw physical brutality before he lovingly and tenderly dances with Juliet’s comatose body, wrapping her limbs around him, wrapping his body around hers, stroking her soft skin, feeling her still-warm body against his own to relive their brief time together. Juliet’s joy at waking to find herself in Romeo’s arms is palpable but of course short lived.

As Lord Capulet and Montague become reconciled in their grief we sense Mercutio’s curse lifting. But the scene is not so long as to detract from the loss of young lives that has precipitated this long overdue reconciliation.

We leave the theatre, our minds astir with images that bring to mind Linda Hutcheon’s concept of adaptation as a “creative act” (8), and our nervousness assuaged. We are great admirers of MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, but we don’t feel comfortable with the notion of a “definitive” adaptation of anything really—it just seems too limiting to us. This adaptation of Shakespeare’s play has emphasised humour and sexual awakening on the one hand, and the pragmatism, grief and violence associated with death on the other. And we’re fine with that.

©British Ballet Now & Then

References

Byrne, Emma. “Romeo and Juliet review: an inspired choice for the Royal Ballet’s return”. The Standard, 6 Oct. 2021, https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/dance/romeo-and-juliet-review-royal-opera-house-b959020.html.

Hutcheon, Linda and Siobhan O’Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation. 2nd ed. Routledge, 2013.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Penguin Books, 1967.

Watts, Graham. “Northern Ballet’s Romeo & Juliet: a plethora of outstanding dancers”. Bachtrack, 29 May 2024, https://bachtrack.com/review-romeo-and-juliet-northern-ballet-sadlers-wells-may-2024.