In September, Julia and Rosie presented a paper at the Theatre & Performance Research Association Conference in Exeter on Cathy Marston and the influence of Regietheater (directors’ theatre) on her choreographic style.

We thought we would share with our readers a version of our script as very little has been written about this aspect of Cathy’s work.

As you probably know, Cathy has been creating dance works for over twenty years and is in demand internationally. Predominantly she is known for her narrative ballets, adaptations of literature, drama and biography. Marston was brought up in the UK, the daughter of two English teachers, a background that led naturally to a love of literature. We really enjoyed her description of her birthday, when she was about 12 years old: evidently, instead of having a party, she requested a visit to Stratford to see The Merchant of Venice(“Interview with Cathy Marston”).

Of course, Marston was also drawn to ballet, and we find it interesting that at the age of around 14 she was already concerned about the meaning of movement and its potential for expression:

I actually took that [RAD] syllabus book to bed … and wrote next to every plié what the particular port de bras meant for me or what that frappé exercise was supposed to express to me. So I think it was always about what the dance was telling rather than how it was happening. (“Delving into Dance”)

After studying for two years at the Royal Ballet Upper School (1992-1994), Marston worked as a dancer in Switzerland (1996-1999) and during this period started to choreograph professionally. However, in addition to choreographing, Marston worked as artistic director of Bern Ballett for six years, from 2007 to 2013. As artistic director and choreographer, Marston was exposed to European theatre practices, in particular Regietheater, often translated as “directors’ theatre” (Boenisch 1).

In this Spotlight post we will examine Marston’s Juliet and Romeo, which she created in 2009 for Bern Ballett, and her biographical ballet Victoria, which premiered earlier this year in Leeds with Northern Ballet. In this way we can examine the negotiation in her work between her British roots and the strong influence of European theatre practice on her approach to adaptation for the ballet stage.

In a recent interview, Marston commented on her understanding of the term Regietheater:

The German attitude is something called Regietheater, which means director’s theatre: the director, and in this case the choreographer, should interpret the text, rather than put it on stage as written. … you can cut the text up inside out, upside down, you could do whatever you want with the source in order to convey your vision

Marston’s description of Regietheater as “cutting up the text inside out and upside down” is akin to Peter M. Boehnisch’s words: “I wonder whether precisely a genuinely emancipatory ‘messing up’ is not the briefest possible description of what the contested Regietheaterdoes …” (5).

In their outlining of Regie both Boenisch and Marvin Carlson highlight the director’s interpretations of “traditional” (Carlson 68), “older” (110) or canonical plays (Boenisch 1). Particularly in the Anglophone world, this is where the director’s role as “creative artist in his or her own right”, as Carlson expresses it (110), or Boenisch’s “messing up”, perhaps seems at its most radical and unsettling.

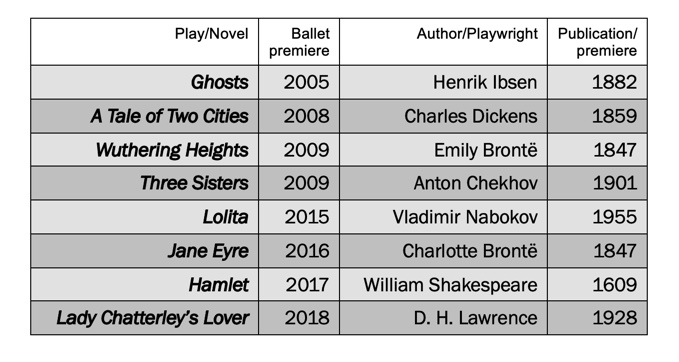

Amongst Marston’s over 60 choreographic works are adaptations of canonical works of literature and drama, including:

The adaptation of a narrative from one medium to another, is by its very nature a creative act, perhaps most obviously when a verbal form is being transposed to a non-verbal form, as in the case of an adaptation from a Shakespearean drama to a ballet. As you know, Romeo and Juliet is an extremely popular ballet across the globe, and the British ballet repertoire already includes a canon of three Romeo and Juliet choreographies, all of them using the score specifically composed by Sergei Prokofiev in 1935 and all of them following the clear structure provided by Prokofiev with its discrete acts and scenes, themes and leitmotifs. They are not the only ballet adaptations of Shakespeare’s play performed by British companies (there is, for example, the innovative Ballet Cymru production from 2013), but these three were all created by revered British choreographers who are in addition identified as creators of an English style of ballet: Frederick Ashton, John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan.

These three Romeo and Juliet ballets were all created between 1955 and 1965 for the Royal Danish Ballet (Ashton), Stuttgart Ballet (Cranko) and Britain’s Royal Ballet (MacMillan). They are large-scale works of high drama that employ rich, colourful décor and costumes representative of the period; as such they complement the sumptuous music score. While each work is distinguished by the variations in choreographic style, there is a certain predictability in their characterisation and linear structure.

By the time Marston choreographed Juliet and Romeo she knew that such an approach would not have been well received well in Bern, where the theatre directorship, critics and audiences were accustomed to a more experimental approach on the part of a director, or choreographer in this case, towards a canonical work. Additionally, Bern Ballett is a small- to mid-scale company and would therefore be unable to provide large numbers of dancers for teeming market and ballroom scenes.

Marston’s approach to this situation was to create a work for 11 dancers representing 11 characters dressed in costumes that might be 21st century or could even be a reference to the 1950s. The stage is framed by scaffolding and stacks of posters that are moved around by the dancers in the course of the performance to create different spaces. The impression is distinctly monochrome. Some of the posters are moved individually and become visible to the audience as posters of Juliet from previous film, theatre, and ballet productions of Romeo and Juliet, including Olivia Hussey in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1963 film. The conflicts take place between Mercutia, Benvolio and Romeo on the side of the Montagues, and Tybalt, Lord Capulet and Paris for the Capulets. Weapons and potions are replaced by a single shard of mirrored glass visibly located downstage when not in use.

We can compare Marston’s production to those of Ashton, Cranko and MacMillan by referring to different traditions of theatre practice. Boehnisch distinguishes the practice of “directing a play” in an English context and “making a performance” in Continental Europe (3). The choreographers Ashton, Cranko and MacMillan indubitably “made a performance” by the incontrovertible fact of having created ballet movement inspired by Shakespeare’s play and Prokofiev’s music. However, because of their adherence to ballet codes of technique, gender, structure, characterisation and music-movement relationship, we argue that the process of creating these productions is also akin to “directing a play”, particularly when compared with Marston’s approach to the same task. The details of Marston’s set and costumes that we have outlined, and the re-gendering of Mercutio are consistent with the notion of “making a performance” and giving a specific direction or purpose to the “text” (5), as Boenisch puts it. Further, Marston as choreographer raises questions of patriarchy, gender, contemporary relevance and relationships between “texts” rather than choreographing the narrative to mirror the Prokofiev score. In this way she also “confronts existing ideas and assumed certainties”, which is a significant aspect of Regie for Boenisch (10).

These properties of Regie – making a performance, giving the text a specific purpose and destabilising certainties – can be observed even more clearly in three striking features of Juliet and Romeo: the unusual structuring of the work, the foregrounding of Juliet and Friar Laurence, and the emphasis on the themes of authority and conflict.

In Prokoviev’s score and the three traditional British adaptations of the ballet, Friar Laurence is a minor and straightforward role. In stark contrast, Marston’s Juliet and Romeo both starts and ends with Juliet and Friar Laurence – the two characters who are in possession of all the facts pertaining to Juliet’s duplicitous “death”. The ballet opens with the scene where Juliet threatens to kill herself, and a motif is established between Juliet and Friar Laurence, whereby the Friar lifts Juliet away from the shard of glass, she pirouettes into him, he catches her and pulls her upstage right, away from the shard’s location.

Another motif is established where Laurence places his hands close to Juliet’s head, thereby drawing her back in time: from this scene in Juliet and Romeo the sequence of events follows the usual trajectory, beginning with the Montagues and Capulets’ initial brawl and ending with the double suicide.

The focus on Friar Laurence and Juliet, and their relationship, is developed as they spend time together at the start of the ballet watching the events that have passed, sometimes also walking amongst the Veronans. Juliet at times seeks to intervene in the action, and repeatedly returns to the thought of suicide. Through the course of the ballet the Friar frequently appears at moments of conflict, moves posters or rolls them up in an understated but deliberate way. At the end of the ballet he brings Juliet downstage, organises her body tidily and places the shard in its usual location, conveying a sense of inevitability to the narrating of this tragedy. Occasionally Juliet rebels against the Friar, pushing him away or running away from him. Ultimately, the conflict within Juliet it is resolved by her death. In our opinion, the prominence of Laurence, whose movements could be interpreted as either manipulative or protective, or both, seems to follow Shakespeare’s portrayal: a prominent figure of authority, an ambiguous character who constructs a dubious plan to reunite the lovers that ends with their death (Herman).

This fascinating restructuring and refocussing of the narrative is underpinned by Marston’s use of the Prokofiev score: appropriately, rather than starting with the love theme of the overture, Juliet and Romeo begins with the “Duke’s Command” that represents Prince Escalus’ warning to the Capulets and Montagues, and through this establishes an atmosphere of “conflict and tragic premonition” (Bennett). This approach is “radically at odds with” traditional ballet adaptations of the narrative, which emphasise the romantic relationship between Romeo and Juliet, a radicalism that is highlighted by Carlson as a feature of Regie (110). For us, the emphasis on conflict, the ambiguity of Friar Laurence’s actions and his role as narrator mark a welcome return to concepts central to Shakespeare’s text.

As we discussed in relation to the British ballet canon of Romeo and Juliet choreographies, the British ballet-going public, unlike the Bern audience, are accustomed to narrative ballets with realistic depiction of time and place and to a straightforward linear rendition of the storyline. We enjoy Marston’s description of this as the “BBC costume drama” approach to adaptation (“Delving into Dance”). Two recent examples of this approach are The Winter’s Tale (2014) and Frankenstein (2016), choreographed for Britain’s Royal Ballet by contemporaries of Marston, Christopher Wheeldon and Liam Scarlett respectively, who, like Marston, are English graduates of the Royal Ballet School.

While Victoria, created for Britain’s Northern Ballet, appears to us less radical than Juliet and Romeo, neither does if conform to the “BBC costume drama” model: although relatively large-scale, with rich costumes recognisably representing the Victorian era, the influence of Regietheater is unmistakable in the structure and presentation of the narrative of Victoria’s life.

You may not be aware that over the course of her lifetime, Queen Victoria was an enthusiastic diarist. Upon her death her youngest child Beatrice took on the task of editing and rewriting the diaries from 122 to 111 volumes, a monumental enterprise that took her more than three decades. The ballet Victoria is framed by Beatrice’s rewriting of her Mother’s diaries, beginning shortly before Victoria’s death, ending with Albert’s death and spanning over sixty years. Therefore the narrative is presented in flashbacks as the audience witnesses Beatrice reading the diaries, the contents of which are simultaneously represented on the stage. Beatrice edits according to her to emotional reactions, including nostalgia and longing; surprise and delight; disapprobation and anger. For the purposes of this process two dancers portray Beatrice: one performs Beatrice as a young woman, and the other the older Beatrice, who is seldom absent from the stage.

There is an intriguing parallel between the way in which Beatrice furiously rips out segments from the journals and Marston “cuts up” and reassembles the “text” of Victoria’s life making a Regie performance. Further, by portraying her life to the audience through the eyes of Beatrice, Marston gives a specific direction and purpose to Victoria’s biographical narrative, a direction that “confronts existing ideas and assumed certainties” (Boenisch 10) about Queen Victoria.

Marston herself refers to Beatrice as an “unreliable witness” (qtd. in Dennison). Her conscious choice of an “unreliable witness” is not only in line with current thinking about the writing of history, but also reflects the approach of Regietheater to the past, according to which the past cannot simply be brought into the present through straightforward representation (Boenisch 29). In discussing this issue Boenisch refers to the term “aesthetic mediation”, which emphasises the “distance and unavailability of the past” (9) integral to the philosophy of Regie. Through aesthetic mediation the past is “re-presented” (29), and the lacuna between the dramatic text (or in this case the dominant narrative of Victoria’s life) and its staging is exploited (30).

Integral to this “aesthetic mediation” in Marston’s ballet are the set and the corps de ballet of archivists: the stage is dominated by bookcases housing Victoria’s red volumes, which gradually over the course of the work the archivists replace with Beatrice’s edited blue volumes. In comparison with more orthodox productions of narrative ballets in this country, such as The Winter’s Tale and Frankenstein, this set is distinguished not only by its essential contribution to the action, but also its relative sparseness and ability to create a number of environments for the purpose of the narrative. In its relative minimalism Victoria cannot compare, for example, with the extreme bareness of Miki Manojlović’s 2015 Romeo and Juliet, set on a metallic cross. However, its imaginative and fluid use of stage space does seem to represent a negotiation between the general expectations of ballet in this country and the influence of Regietheater that has become integral to Marston’s choreographic style.

Echoing Boenisch’s words, Marston’s experience of encountering Regietheater she describes as liberating: “You can really take pieces, take traditional, archetypal works of literature or mythology and extract what inspires you, and that’s really given me the freedom to find my own voice (“Interview”). Victoria is an iconic monarch whose persona is indubitably imbued with the mythology of the “Widow of Windsor”, a queen grieving for her consort for almost four decades in her black bombazine, symbolic of the deepest mourning. In Act I the audience witnesses this well worn image of Victoria: in Act II the young Victoria emerges in all her ebullience, with her sense of fun, and the intense physicality of her passion, expressed both in abject rage and in the euphoria of sexual pleasure. By drawing an analogy between the myth of Victoria and a playtext, we can describe this production as what Boenisch terms a “play-performance” and conclude that “our perception and understanding [of Queen Victoria] is ultimately changed through the play-performance afforded by Regie” (9).

As far as we can see, Cathy Marston’s approach to adapting narrative for the dance stage, wherever in the globe that might be, is driven by concepts and ideas rather than linearity and “fidelity” to the text being adapted (Hutcheon and O’Flynn). In the case of both Juliet and Romeo and Victoria, choreographed a decade apart in different contexts, what we thought we knew about figures from the canon of English literature and British history is questioned in a way that goes “beyond established paradigms of meaning” (Boenisch 5), revealing their “inherent contradictions ” (10). This is achieved through integrating features of the “emancipatory ‘messing up’” that is Regietheater (5).

Narrative ballets, mostly adaptations of existing narratives, have been crucial to the British ballet repertoire since its inception in the late 1920s. Now, in the 21st century, Marston has developed an approach to creating narrative choreographic works that on the one hand, as she says “respects” her sources, as in the British tradition (“Interview”), but on the other hand challenges audience perception of the subject matter, in a way the owes much to the influence of living and working in Continental Europe.

In February next year Marston’s The Cellist, a ballet about Jacqueline du Pré, premieres at Covent Garden. An imaginative subject matter, as so often. We look forward to seeing how Marston approaches her chosen topic, and wait with bated breath to see what she has in store for us in the future …

© British Ballet Now & Then

We would like to thank Cathy Marston for her help and support in the writing of this post, and of course for her marvellous choreography!

References

Bennett, Karen. “Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet and Socialist Realism: a Case-Study in Inter-semiotic Translation”. Shakespeare and European Politics, edited by Dirk Delabastita, Josef de Vos, Paul Franssen, U of Delaware P, 2008, pp. 318-28.

Boenisch, Peter. Directing Scenes and Senses: the thinking of Regie. Manchester UP, 2015.

Carlson, Marvin. Theatre: a very short introduction. Oxford, UP, 2014.

“Cathy Marston”. Delving into Dance, 28 May, 2018, http://www.delvingintodance.com/podcast/cathy-marston. Accessed 23 Aug. 2019.

Dennison, Matthew. “Victoria through the eyes of her favourite child: how the life of Queen Victoria became a ballet”. The Telegraph, 25 Feb. 2019, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/dance/what-to-see/victoria-eyes-favourite-child-life-queen-victoria-became-ballet/. Accessed 11 June 2019.

Herman, Peter C. “Tragedy and the Crisis of Authority in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet”. Intertexts, vol. 12, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 89-110.

Hutcheon, Linda and Siobhan O’Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation. 2nd ed. Routledge, 2013.

“Interview with Cathy Marston”. YouTube, uploaded by Cathy Marston, 18 Aug. 2014,www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsI0ELIRU8E. Accessed 9 Nov. 2019.

Marston, Cathy. Cathy Marston: choreographer, artistic director. 2010-2018, http://www.cathymarston.com/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2019.

McCulloch, Lynsey. “’Here’s that shall make you dance’: Movement and Meaning in Bern: Ballett’s Julia und Romeo”. Reinventing the Renaissance: Shakespeare and his Contemporaries in Adaptation and Performance, edited by Sarah Brown, Robert Lublin, Lynsey McCulloch. Palgrave MacMillan, 2013, pp. 255-268.

Rosie & Julia: That’s a pretty rigorous and thoroughgoing paper, and I trust that it was well received when delivered. I must be one of a select band of Brits who saw J&R in Bern – my wife and I went over just before Christmas that year when we also managed to see most of the Company doing their stuff in “Sweet Charity” that was also on at the Stadtheater on the previous evening!

On the evidence of our visit, Bern loved J&R and I believe it had gone down well with the critics. They had been rather less warm, I think, about Cathy’s first piece for the Company a couple of years earlier – a version of Firebird set in the Romanov court in the time of Rasputin, as part of an otherwise contemporary Triple Bill (Hans van Manen & Doug Varone). The costuming then was much as one might have expected of a Royal Ballet production and quite different from the approach in 2009, possibly just one of the changes in approach that Cathy felt she had to make out there. Another thing I’d mention is that, for probably most of her dancers, R&J may have been their first experience of dancing a full-evening narrative work, one that I’d dearly like to see revived here sometime!

LikeLike

Thank you, Ian! Such interesting information 🙂

LikeLike